Partner Peter Doyle

Queer Places:

246 Old Walt Whitman Rd, Huntington Station, NY 11746, Stati Uniti

99 Ryerson St, Brooklyn, NY 11205, USA

328 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Camden, NJ 08103, Stati Uniti

431 Stevens St, Camden, NJ 08103, Stati Uniti

Harleigh Cemetery, 1640 Haddon Ave, Camden, NJ 08103, Stati Uniti

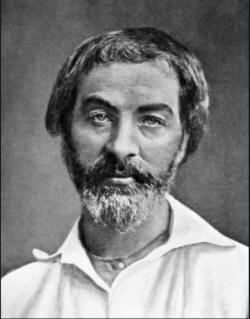

Walter

"Walt" Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist,

and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between

transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman

is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the

father of free verse.[1]

His work was very controversial in its time, particularly his poetry

collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its

overt sexuality. Such major figures as

Emily Dickinson,

Ralph Waldo Emerson, and

Margaret Fuller glorified

same-sex friendship, while Walt Whitman

filled his poetry with robust imagery celebrating male "ashesiveness".

Louisa May Alcott extolled

the virtues of intimate same-sex friendship in her 1870 novel An Old-Fashioned

Girl, in which she describes the lives of two women artists.

Walter

"Walt" Whitman (May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist,

and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between

transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman

is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the

father of free verse.[1]

His work was very controversial in its time, particularly his poetry

collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its

overt sexuality. Such major figures as

Emily Dickinson,

Ralph Waldo Emerson, and

Margaret Fuller glorified

same-sex friendship, while Walt Whitman

filled his poetry with robust imagery celebrating male "ashesiveness".

Louisa May Alcott extolled

the virtues of intimate same-sex friendship in her 1870 novel An Old-Fashioned

Girl, in which she describes the lives of two women artists.

Born in Huntington on Long Island, Whitman worked as a journalist, a teacher, a government clerk, and—in addition to publishing his poetry—was a volunteer nurse during the American Civil War. Early in his career, he also produced a temperance novel, Franklin Evans (1842). Whitman's major work, Leaves of Grass, was first published in 1855 with his own money. The work was an attempt at reaching out to the common person with an American epic. He continued expanding and revising it until his death in 1892. After a stroke towards the end of his life, he moved to Camden, New Jersey, where his health further declined. When he died at age 72, his funeral became a public spectacle.[2][3]

Though biographers continue to debate Whitman's sexuality, he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Whitman's sexual orientation is generally assumed on the basis of his poetry, though this assumption has been disputed. His poetry depicts love and sexuality in a more earthy, individualistic way common in American culture before the medicalization of sexuality in the late 19th century.[128] Though Leaves of Grass was often labeled pornographic or obscene, only one critic remarked on its author's presumed sexual activity: in a November 1855 review, Rufus Wilmot Griswold suggested Whitman was guilty of "that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians."[129]

Walt Whitman's 1856 Leaves of Grass included one of XIX century's America's major sex manifestos, a passionate prose plea for the open treatment of sexuality in the nation's literature. This appeared in an open letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson who, in a rhapsodic private letter to Whitman, had praised the writer's first edition, then found his private communication reprinted, without permission, in Whitman's second edition.

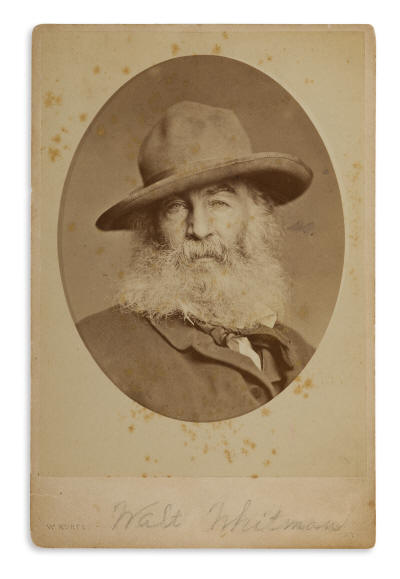

WILLIAM KURTZ (1833-1904)

Walt Whitman.

Albumen print, the image measuring 114.3x88.9 mm; 4 1/2x3 1/2 inches, the sheet 139.7x101.6 mm; 5 1/2x4 inches, the cabinet card mount 165.1x108 mm; 6 1/2x4 1/4 inches, with Kurtz's printed credit, and the notation "872 B Way, NY" and the title, in pencil, in an unknown hand, on mount recto. Circa 1867-69.

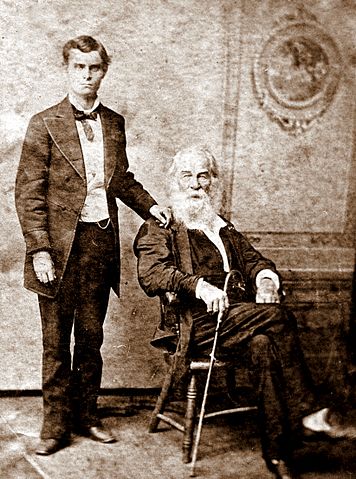

Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle

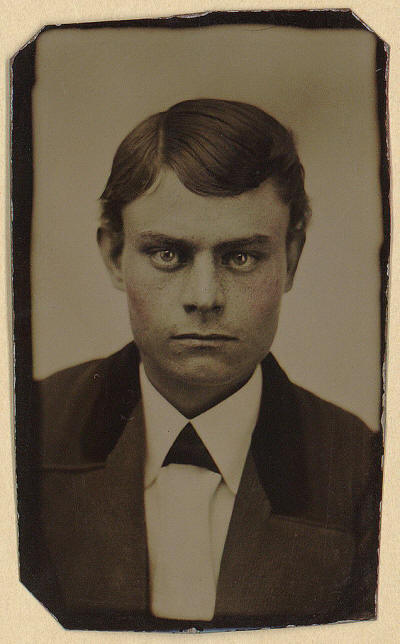

Harry Stafford

Harry Stafford and Walt Whitman

![Horace Traubel, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing left] / Gilbert & Bacon, photographers. | Library of Congress](http://www.elisarolle.com/images/images%20005/timeline-traubel.jpg)

Horace Traubel

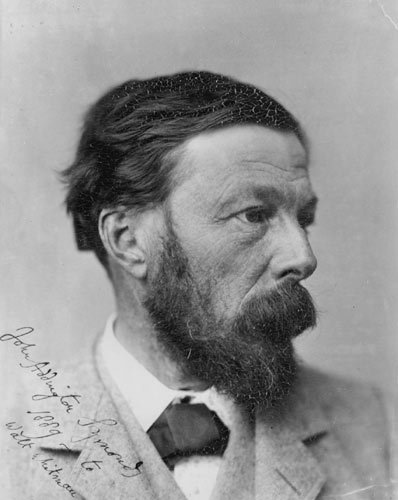

John Addington Sumonds, 1889, signed to Walt Whitman

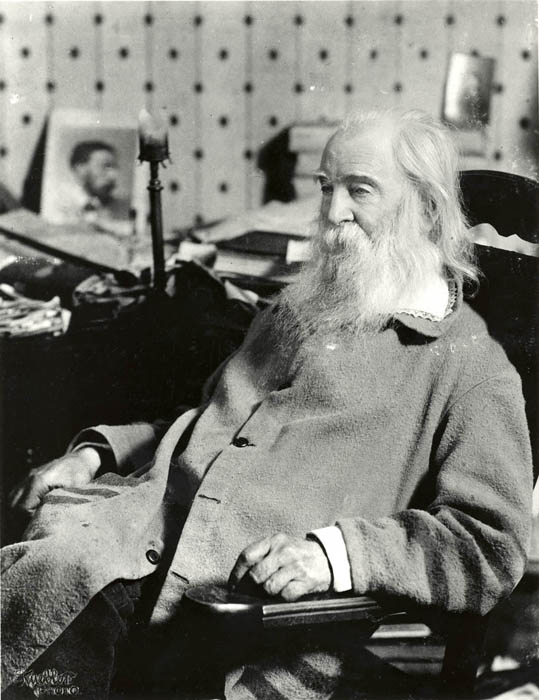

Walt Whitman with Symonds' photo on the desk

Walt Whitman, the grand master of comradeship, adhering to Bill Duckett, 1886

Walt Whitman Service Area, NJ

Walt Whitman's sexual poems had a seductive and unnerving effect on Henry David Thoreau. With Bronson Alcott (the write Louisa May Alcott's father) and Sarah Tyndale, he trekked in 1856 to visit the poet in New York in order to confront the daring word worker in his native habitat. "That Walt Whitman... is the most interesting fact to me at present," Thoreau wrote privately to a friend a short time later. "I have just read his second edition of Leaves of Grass (which he gave me) and it has done me more good than any reading for a long time." But Thoreau was also alarmed: "There are 2 or 3 pieces in the book which are disagreeable to say the least, simply sensual. He does not celebrate love at all. It is as if the beasts spoke. I think that men have not been ashamed of themselves without reason."

On a sharp late-winter’s day early in 1860 on Boston Common, America’s Plato, Ralph Waldo Emerson, perhaps Harvard’s most illustrious graduate still, walked the Beacon Street path the better part of several hours with the poet most would agree is America’s greatest. Back and forth, up and down, Whitman confronted Emerson’s misgivings and foreboding about the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass with deep feeling that day: the end of it all, what Whitman called “a bully dinner”1—and the publication of perhaps the most famous homosexual poetry ever written.

Canadian born in 1837 of Irish parents, Frederick B. Vaughan lived with Walt Whitman while the poet finished his "Calamus" poems which their love helped shape. After hearing a Ralph Waldo Emerson's lecture of Leaves of Grass, Vaughan wanted New York to erect a Fred-Walt statue "with an immense placard on our breasts, reading SINCERE FRIENDS!!!". In 1860 Whitman sent Vaughan galleys from Boston when the 1860 Leaves of Grass went to press. Bemoaning lover problems, Whitman in 1870 compared Vaughan with Peter Doyle, admonishing himself: "Remember Fred Vaughan". Vaughan confessed to Whitman: "Father used to tell me I was lazy. Mother denied it. . . . I used to tell your mother you was lazy and she denied it". Vaughan's drinking (frequently in Pfaff's) ended in what he called their "estrangement". In 1862 Vaughan married, and he eventually became the father of four children. Whitman left New York and seldom returned. After Vaughan visited Camden in 1890, Whitman told Horace Traubel, "Yes: I have seen him off and on—but now, poor fellow, he is all wrecked from drink". The date of Vaughan's death is unknown. Despite his estrangement from Whitman, Vaughan wrote a poem about Williamsburg Ferry (with echoes of "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry") which concludes: "From among all out of all Connected with all and yet distinct from all arises thee Dear Walt".

There is also some evidence that Whitman may have had sexual relationships with women. He had a romantic friendship with a New York actress, Ellen Grey, in the spring of 1862, but it is not known whether it was also sexual. He still had a photograph of her decades later, when he moved to Camden, and he called her "an old sweetheart of mine".[148] In a letter, dated August 21, 1890, he claimed, "I have had six children—two are dead". This claim has never been corroborated.[149] Toward the end of his life, he often told stories of previous girlfriends and sweethearts and denied an allegation from the New York Herald that he had "never had a love affair".[150] As Whitman biographer Jerome Loving wrote, "the discussion of Whitman's sexual orientation will probably continue in spite of whatever evidence emerges."[130]

Lewis (aka Lew or Lewy) K. Brown left his family's farm near Elkton, Maryland, to join the Union army. Walt Whitman met him in February 1863 in the Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C., where Brown was recovering from a wound in the left leg, which he had received in a battle near Rappahannock Station in August 1862. His affectionate nature made him receptive to Whitman's nurturing ministrations, and it was through Brown that Whitman formed close attachments to several other wounded soldiers. Whitman reported in letters to Brown's friend Sergeant Thomas P. Sawyer that Brown gave him a kiss "half a minute long" and that he hoped to live with both Sawyer and Brown after the war was over, suggesting that his interest in the two young soldiers (among others) may have been more than paternal. Although his feelings for Sawyer may have been even stronger than those he felt for Brown, Whitman's letters to Brown say the sight of Brown's face was "welcomer than all," and he refers to Brown as "my darling". On 5 January 1864 Brown's leg was amputated five inches below the knee, and Whitman spent two nights on a cot near his bed to see him through the painful experience. Brown left the army in August 1864, and a year later he was employed as a clerk in the Treasury Department. As late as 1867, Whitman wrote to Hiram Sholes that Brown was well and that he saw him often. In 1880 Brown became Chief of the Paymaster's Division and remained in that position until his retirement in 1915.

Peter Doyle and Whitman met one winter's evening in 1866 in Washington, D.C. The twenty-one-year-old Doyle was the conductor on a Pennsylvania Avenue horsecar, and the forty-five-year-old Whitman was the car's sole passenger. Doyle recalled, "We were familiar at once—I put my hand on his knee—we understood . . . From that time on, we were the biggest sort of friends". In some respects Doyle seems an unlikely companion for "America's poet." Born in Limerick, Ireland, on 3 June 1843, and reared in America's South, Doyle came into manhood armed as a Confederate soldier against the Union that Whitman held so dear. A marginally literate working man, Doyle was no intellectual or social match for Whitman, the well-known poet and federal employee whose Washington friends included Lincoln's former secretary, John Hay, Ohio Congressman James Garfield, and Attorney General J. Hubley Ashton. Yet, in ways that mattered more, Doyle was precisely the kind of man Whitman loved best. The poet always followed his own admonition, laid down in the Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass, to "go freely with powerful uneducated persons". In his youthful grace and good health, Doyle was a welcome tonic for the war-weary Whitman, who had spent the previous two years in Washington's army hospitals nursing the wounded. They spent long afternoons riding the streetcars, or eating fresh fruits at Center Market. Evenings were reserved for moonlit walks along the Potomac River that had Whitman reciting Shakespeare's sonnets to Doyle, and Doyle relating his favorite limericks to Whitman. Whitman also relished the opportunity to be part of the young man's large family circle. It included Doyle's widowed mother, Catherine, and his younger brother Edward and sister Margaret, for whom Pete made a home. Also nearby were the families of married brothers James and Francis, and aunt Ann and uncle Michael Nash, whom Whitman counted among his dear friends. Doyle is usually associated with Whitman's "Calamus" poems, although he did not serve as the muse for these tender verses first published in 1860. The satisfaction that Whitman derived from his relationship with Doyle, however, may have influenced him to drop several of the more anxiety-ridden "Calamus" poems in editions of Leaves of Grass brought out after 1865. Whitman's expressed affection for the former Confederate artilleryman reinforced the theme of reconciliation in the poet's war writings. The eyewitness narrative of Lincoln's assassination found in Memoranda During the War (1875–1876) may have been inspired by Doyle, who was at Ford's Theater on that fateful Good Friday. A stroke that Whitman suffered on 23 January 1873 caused him to settle later that year in Camden, New Jersey, with his brother George and sister-in-law Louisa. The intensity of Whitman's friendship with Doyle waned with time and distance. In New Jersey, Harry Stafford provided Whitman with a measure of the companionship that Doyle was not there to give. In the mid-1880s Whitman and Doyle renewed their intimacy when Doyle—now employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad as a baggage master—settled in Philadelphia and made weekly visits to Whitman in Camden. The round-the-clock presence of caretakers during the poet's last years eventually alienated Doyle, whose calls became infrequent. Before Whitman's death on 26 March 1892, Doyle explained to Whitman the reason why he visited so rarely, and the old man understood. Doyle attended Whitman's funeral at Harleigh Cemetery. Peter Doyle made a lasting contribution to Whitman biography in 1897 when he allowed Richard Maurice Bucke to edit and publish Whitman's letters to Doyle, which Doyle had entrusted to Bucke in 1880. Included with the letters was Bucke's interview of Doyle, which Henry James in his 1898 review of the book called "the most charming passage in the volume". Doyle was a member of the Walt Whitman Fellowship and enjoyed the friendship of Horace and Ann Traubel, Gustave Percival Wiksell, and publisher Laurens Maynard. Doyle continued to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad until his death on 19 April 1907 at age 63.

On February 8, 1867, Charles Warren Stoddard, first wrote from San Francisco to Walt Whitman, beseeching him for an autograph. Whitman did not respond. But two years later, on March 2, 1869, the determined Stoddard wrote again, this time from Honolulu. Stoddard justified his persistence with Whitman's own come-on, quoted from Leaves of Grass: Stranger! if you, passing, meet me, and desire to speak to me, why should you not speak to me? And why should I not speak to you? On June 12, 1869, from Washington, D.C., Whitman responded positively to Stoddard's call. The poet was fascinated by Stoddard, and even curious to meet him. Stoddard never arranged a meeting, despite Whitman's repeated invitations.

Whitman had intense friendships with many men and boys throughout his life. Some biographers have suggested that he may not have actually engaged in sexual relationships with males,[130] while others cite letters, journal entries, and other sources that they claim as proof of the sexual nature of some of his relationships.[131] John Addington Symonds first read Whitman in 1865, and began corresponding with him six years later, in 1871. His most famous letter was written in August of 1890 wherein, after years of indirect questioning, Symonds directly asked Whitman about the homosexual content of the "Calamus" poems. Symonds spent 20 years in correspondence trying to pry the answer from him.[132] In 1890 he wrote to Whitman, "In your conception of Comradeship, do you contemplate the possible intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men?" In reply, Whitman denied that his work had any such implication, asserting "[T]hat the calamus part has even allow'd the possibility of such construction as mention'd is terrible—I am fain to hope the pages themselves are not to be even mention'd for such gratuitous and quite at this time entirely undream'd & unreck'd possibility of morbid inferences—wh' are disavow'd by me and seem damnable," and insisting that he had fathered six illegitimate children. Some contemporary scholars are skeptical of the veracity of Whitman's denial or the existence of the children he claimed.[133]

After suffering a paralytic stroke in early 1873, Whitman was induced to move from Washington to the home of his brother—George Washington Whitman, an engineer—at 431 Stevens Street in Camden, New Jersey. His mother, having fallen ill, was also there and died that same year in May. Both events were difficult for Whitman and left him depressed. He remained at his brother's home until buying his own in 1884.[97] However, before purchasing his home, he spent the greatest period of his residence in Camden at his brother's home in Stevens Street. While in residence there he was very productive, publishing three versions of Leaves of Grass among other works. He was also last fully physically active in this house, receiving both Oscar Wilde and Thomas Eakins. His other brother, Edward, an "invalid" since birth, lived in the house.

When asked by a reporter upon docking in New York who were the greatest American literary figures, Oscar Wilde at once answered Walt Whitman, but in the same breath insisted also on Ralph Waldo Emerson—“New England’s Plato,” Wilde called him, whose “Attic genius” he thought so highly of that when he was in prison and allowed to choose only a few books, one was Emerson’s essays. He quoted from Emerson twice in De Profundis—and very significant quotes they were: “Nothing is more rare in any man than an act of his own”; “all martyrdoms seemed mean to the lookers on.” According to Richard Ellmann, Wilde (who after his visit to Whitman answered not one but all questions about the American poet’s sexuality for years to come by repeating, “The kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips”) expanded on the matter significantly: under an inscription by Whitman, Wilde (quoting himself about Wordsworth; it was nothing if not a literary age) wrote of Whitman: “The spirit who living blamelessly but dared to kiss the smitten mouth of his own century.”

When his brother and sister-in-law were forced to move for business reasons, he bought his own house at 328 Mickle Street (now 330 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard).[98] First taken care of by tenants, he was completely bedridden for most of his time in Mickle Street. During this time, he began socializing with Mary Oakes Davis—the widow of a sea captain. She was a neighbor, boarding with a family in Bridge Avenue just a few blocks from Mickle Street.[99] She moved in with Whitman on February 24, 1885, to serve as his housekeeper in exchange for free rent. She brought with her a cat, a dog, two turtledoves, a canary, and other assorted animals.[100] During this time, Whitman produced further editions of Leaves of Grass in 1876, 1881, and 1889.

Harry L. Stafford was only eighteen years old in 1876 when he took a job as an errand boy at the Camden New Republic. He was a moody adolescent, given to fits of brooding and impulsive behavior. Walt Whitman, then 57 and still recovering from his stroke of 1873, came to the office to work on the Centennial edition of Leaves of Grass, and the two began one of the most intense relationships of the poet's life. Stafford took Whitman to visit his parents at White Horse Farm, near Kirkwood, New Jersey. The farm adjoined Timber Creek (now called Laurel Springs), and Whitman made his way down to the creek to regenerate his health by wrestling with birch saplings and taking "Adamic" mud baths. He also found time to meet there with a Stafford farm hand named Ed Cattell, but he kept those encounters secret from Stafford. Stafford and Whitman slept together in the same top floor bedroom, and when they traveled together Whitman referred to him as "my nephew" and insisted that they be accommodated in the same bed. Whitman's friend John Burroughs complained that they "cut up like two boys", and he found their frolicsome behavior annoying. The Stafford family, however, were pleased to see the well-known man act as mentor to their son and gladly forgave any bad manners, chalking them up to artistic temperament. They hung a picture of the poet on their sitting room wall. Despite the frolicking, the relationship was a stormy one. They quarreled frequently, and several times Stafford returned a friendship ring given to him by Whitman. Stafford wrote that there was "something wanting to complete our friendship", perhaps meaning sexual relations. At another time, he wrote of wanting to buy a suit of clothes like Whitman's so he could earn the admiration of his friends. He also wrote, "I am thinking of what I am shielding, I want to try and make a man of myself", perhaps referring to guilt about homosexuality or simply to immaturity. The nature of their bond remains mysterious, and critics have interpreted it as everything from asexual and paternal to erotic and promiscuous. Whitman seems to have been less ambivalent. He wrote in his notebooks of their peaceful times together and of his dismay at Stafford's mercurial anxiety. At one point, he wrote of his gratitude for Stafford's help in his medical recovery, declaring, "you, my darling boy, are the central figure of them all". Stafford went from one job to another until he returned to the family farm. He and Whitman remained close until Stafford married Eva Westcott in 1884, after which the poet visited occasionally. When he died, Whitman left Stafford his silver watch, originally intended for Peter Doyle.

Edward Carpenter visited the poet for several weeks in 1877 and again in 1884. In 1906 he published an account of his visits to America, Days with Walt Whitman, writing a respectful, even somewhat glorified, portrait of his idol. In 1924, Edward Carpenter told Gavin Arthur of a sexual encounter in his youth with Whitman, the details of which Arthur recorded in his journal.[140][141][142]

While in Southern New Jersey, Whitman spent a good portion of his time in the then quite pastoral community of Laurel Springs, between 1876 and 1884, converting one of the Stafford Farm buildings to his summer home. The restored summer home has been preserved as a museum by the local historical society. Part of his Leaves of Grass was written here, and in his Specimen Days he wrote of the spring, creek and lake. To him, Laurel Lake was "the prettiest lake in: either America or Europe."[101]

Another possible lover was Bill Duckett. As a teenager, he lived on the same street in Camden and moved in with Whitman, living with him a number of years and serving him in various roles. Duckett was 15 when Whitman bought his house at 328 Mickle Street. From at least 1880, Duckett and his grandmother, Lydia Watson, were boarders, subletting space from another family at 334 Mickle Street. Because of this proximity, it is obvious that Duckett and Whitman met as neighbors. Their relationship was close, with the youth sharing Whitman's money when he had it. Whitman described their friendship as "thick". Though some biographers describe him as a boarder, others identify him as a lover.[145] Their photograph [pictured] is described as "modeled on the conventions of a marriage portrait", part of a series of portraits of the poet with his young male friends, and encrypting male–male desire.[146] Yet another intense relationship of Whitman with a young man was the one with Harry Stafford, with whose family Whitman stayed when at Timber Creek, and whom he first met when Stafford was 18, in 1876. Whitman gave Stafford a ring, which was returned and re-given over the course of a stormy relationship lasting several years. Of that ring, Stafford wrote to Whitman, "You know when you put it on there was but one thing to part it from me, and that was death."[[147]

Oscar Wilde met Whitman in America in 1882 and told the homosexual-rights activist George Cecil Ives that Whitman's sexual orientation was beyond question —"I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips."[139] The only explicit description of Whitman's sexual activities is secondhand.

Late in his life, when Whitman was asked outright whether his "Calamus" poems were homosexual, he chose not to respond.[143] The manuscript of his love poem "Once I Pass'd Through A Populous City", written when Whitman was 29, indicates it was originally about a man.[[144]

As the end of 1891 approached, he prepared a final edition of Leaves of Grass, a version that has been nicknamed the "Deathbed Edition." He wrote, "L. of G. at last complete—after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old."[102] Preparing for death, Whitman commissioned a granite mausoleum shaped like a house for $4,000[103] and visited it often during construction.[104] In the last week of his life, he was too weak to lift a knife or fork and wrote: "I suffer all the time: I have no relief, no escape: it is monotony—monotony—monotony—in pain."[105]

Whitman died on March 26, 1892.[106] An autopsy revealed his lungs had diminished to one-eighth their normal breathing capacity, a result of bronchial pneumonia,[103] and that an egg-sized abscess on his chest had eroded one of his ribs. The cause of death was officially listed as "pleurisy of the left side, consumption of the right lung, general miliary tuberculosis and parenchymatous nephritis."[107] A public viewing of his body was held at his Camden home; over 1,000 people visited in three hours.[2] Whitman's oak coffin was barely visible because of all the flowers and wreaths left for him.[107] Four days after his death, he was buried in his tomb at Harleigh Cemetery in Camden.[2] Another public ceremony was held at the cemetery, with friends giving speeches, live music, and refreshments.[3] Whitman's friend, the orator Robert Ingersoll, delivered the eulogy.[108] Later, the remains of Whitman's parents and two of his brothers and their families were moved to the mausoleum.[109]

My published books: