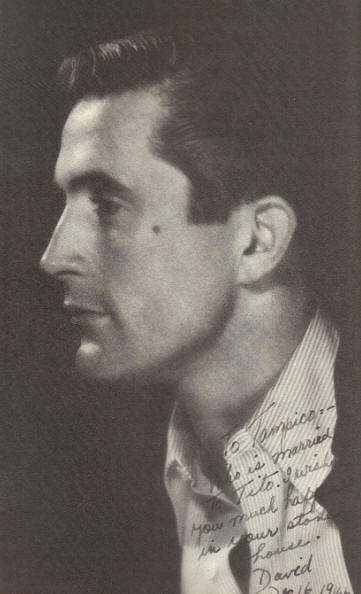

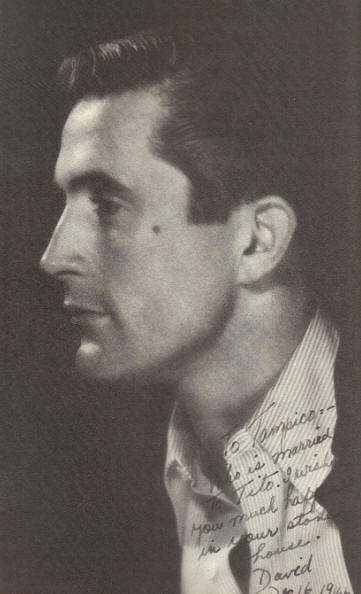

Partner David Gray

Queer Places:

Rainbow Room, 30 Rockefeller Plaza 65th Floor, New York, NY 10112

2118 Kew Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90046

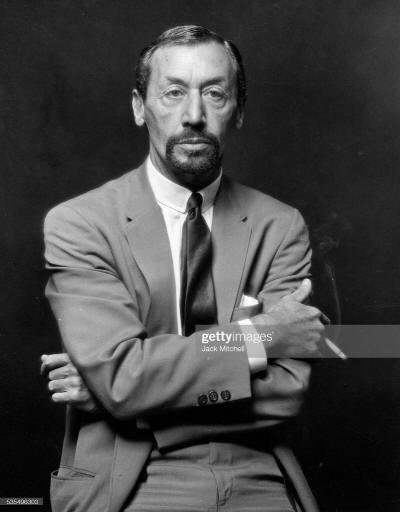

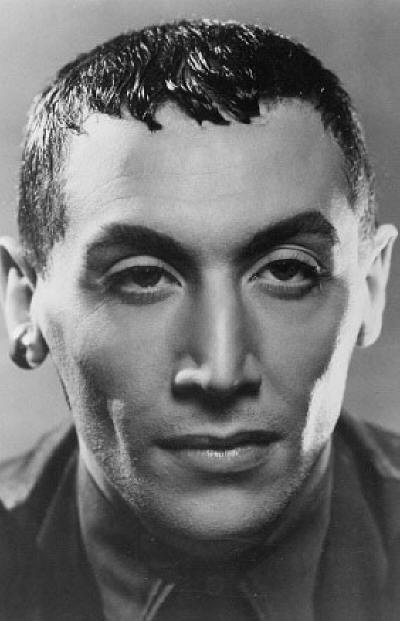

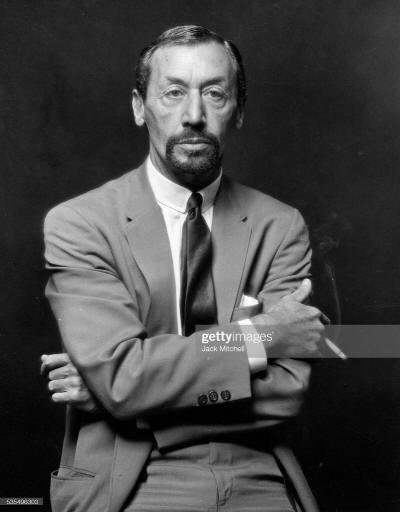

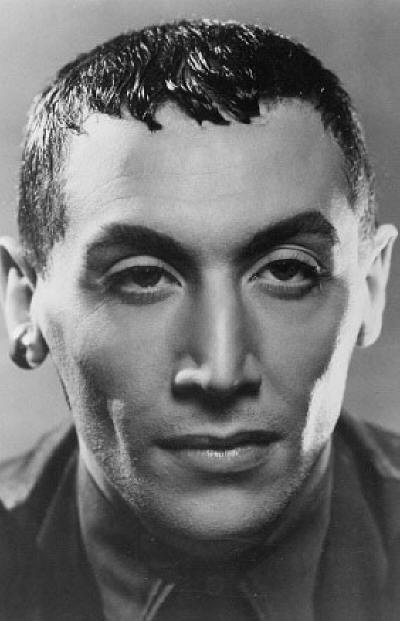

Jack Cole (April 27, 1911 – February 17, 1974) was an American dancer, choreographer, and theatre director known as "the Father of Theatrical Jazz Dance".[1]

Producer Arthur Freed, who was not gay, never had as his purpose the

creation of a team of gay artists for MGM, nor were all the members of the

Arthur Freed unit gay. Freed did want a first-rate team, however, and

hired without regard to sexual orientation. A large number of the gifted

people on it turned out to be gay, including composers

Cole Porter,

Frederick Loewe,

Robert Wright, and

Chet Forrest, choreographers

Robert Alton and

Jack Cole, and directors

Charles

Walters and the closeted Vincente Minnelli.

Influential gay choreographers included Charles Walters, Robert Alton and

Jack Cole (who created Jane Russell’s number with the massed body-builders

in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes).

Jack Cole (April 27, 1911 – February 17, 1974) was an American dancer, choreographer, and theatre director known as "the Father of Theatrical Jazz Dance".[1]

Producer Arthur Freed, who was not gay, never had as his purpose the

creation of a team of gay artists for MGM, nor were all the members of the

Arthur Freed unit gay. Freed did want a first-rate team, however, and

hired without regard to sexual orientation. A large number of the gifted

people on it turned out to be gay, including composers

Cole Porter,

Frederick Loewe,

Robert Wright, and

Chet Forrest, choreographers

Robert Alton and

Jack Cole, and directors

Charles

Walters and the closeted Vincente Minnelli.

Influential gay choreographers included Charles Walters, Robert Alton and

Jack Cole (who created Jane Russell’s number with the massed body-builders

in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes).

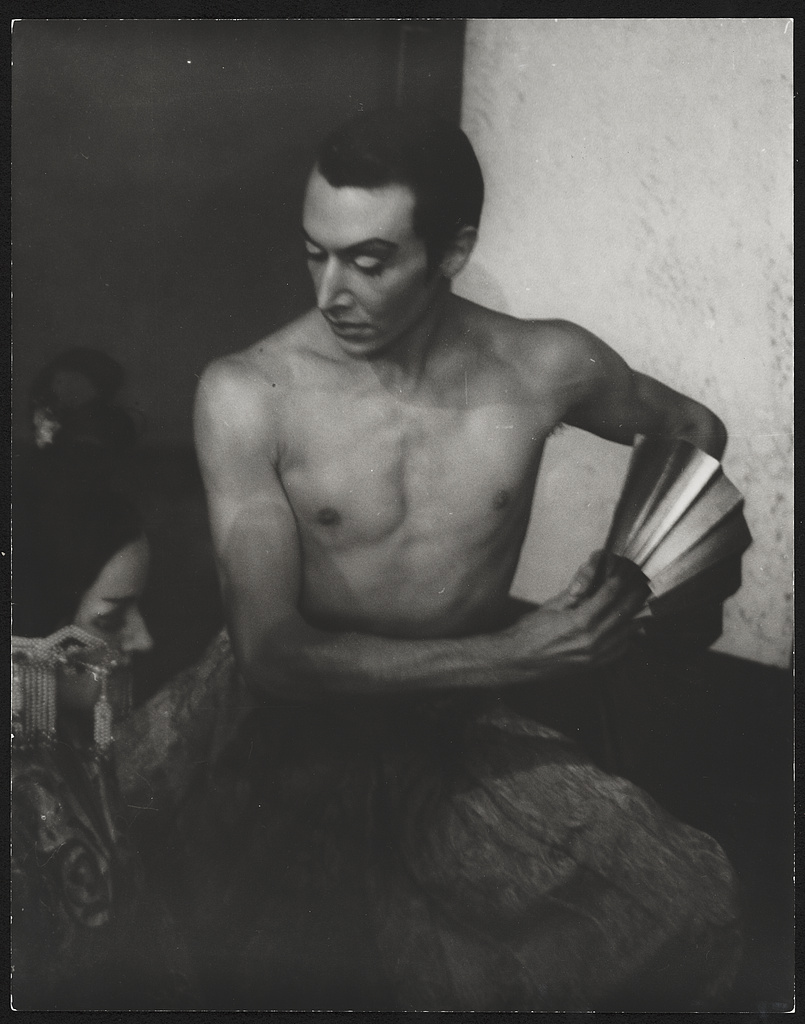

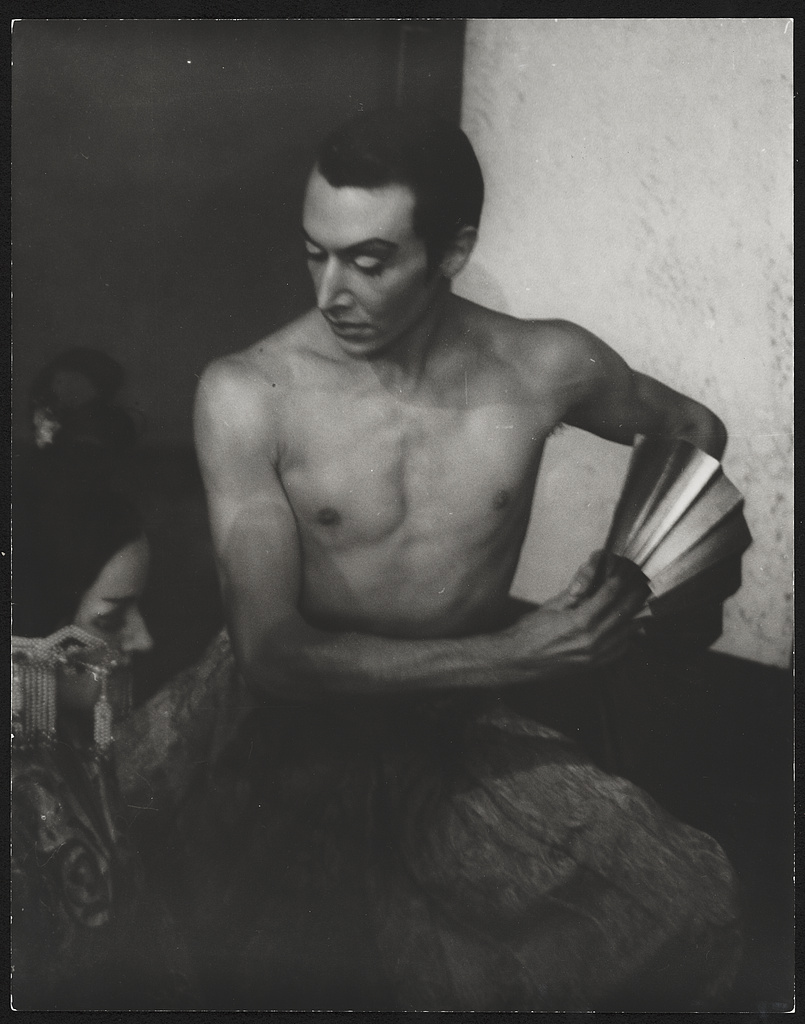

Jack Cole, born John Ewing Richter, made his professional dance debut with Denishawn at Lewisohn Stadium in New York City in August 1930. Only months earlier, he had begun his training as a modern dancer, studying with

Ruth St. Denis and

Ted Shawn. Cole was entranced by the Asian influences Denishawn utilized in its choreography and costuming.[2] Cole also performed briefly with Humphrey-Weidman, and was influenced by the pioneering modernists, Doris Humphrey and

Charles Weidman.[3] Eager to make a living as a dancer during the Depression, Cole soon left the modern dance world and opted for opportunities in nightclubs, where he partnered, first, Alice Dudley, and then for years danced as part of a trio with Anna Austin and Florence Lessing.

Cole's career trajectory was a unique one for an American dance artist. He started at the very roots of modern dance, then segued into a blazing commercial career in nightclubs across the nation, first at Manhattan's Embassy Club, then opening the Rainbow Room on its inaugural evening in October 1934. His career spanned three major arenas: nightclub, Broadway stage, and Hollywood film. He ended his career as a desired coach to Hollywood stars and a highly innovative choreographer for the camera.[4]

by Carl Van Vechten

.jpg)

David Gray

Cole was a performer in Broadway musicals, starting with The Dream of Sganarelle in 1933. His first Broadway credit as a choreographer was Something for the Boys in 1943. Cole is credited with choreographing and/or directing the stage musicals Alive and Kicking, Magdalena, Carnival in Flanders, Zenda, Foxy, Kismet, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Kean, Donnybrook!, Jamaica, and Man of La Mancha.

He studied the Indian dance form Bharata Natyam and used other ethnic material in his dances. The Jack Cole Dancers performed in nightclubs in the late 1930s, including the Rainbow Room.[5]

His film work includes Moon Over Miami, Cover Girl, Tonight and Every Night, Gilda, Down to Earth, The Merry Widow, Meet Me After the Show, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, On the Riviera, There's No Business Like Show Business, The I Don't Care Girl, The Thrill of Brazil, Kismet, Les Girls, Let's Make Love, Some Like it Hot, Designing Woman, Three for the Show, Lydia Bailey, Eadie Was a Lady and many others. He was famous in Hollywood for his work with Rita Hayworth, Betty Grable, Jane Russell, Mitzi Gaynor and Marilyn Monroe. Cole worked closely with Monroe in particular, influencing her iconic performance in "Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend" from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and in five other films.[6] Although Howard Hawks is credited as the sole director of "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes", both the film's co-star Jane Russell and assistant choreographer Gwen Verdon contend that Monroe's iconic musical number, "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend", was actually directed by choreographer Cole. Russell said, "Howard Hawks had nothing to do with the musical numbers. He was not even there."[7]

Cole virtually invented the idiom of American show dancing known as "theatrical jazz dance." He developed a mode of jazz-ethnic-ballet that prevails as the dominant dancing style in today's musicals, films, nightclub revues, television commercials and music videos.[8] According to Martin Gottfried, Cole "won a place in choreographic history for developing the basic vocabulary of jazz dancing—the kind of dancing done in nightclubs and Broadway musicals."[9]

Cole-style dancing is acrobatic and angular, using small groups of dancers rather than a large company; it is closer to the glittering nightclub floor show than to the ballet stage.[10]

Cole is remembered as the prime innovator of the theatrical jazz dance heritage.[1]

Cole's unmistakable style endures in the work of Gwen Verdon, Bob Fosse,

Jerome Robbins, Gower Champion, Peter Gennaro,

Michael Bennett,

Tommy Tune, Patsy Swayze,

Alvin Ailey (who was a dancer in the musical Jamaica), and countless other dancers and choreographers including Wayne Lamb. Cole's choreography in the "Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend" sequence in the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was reinterpreted by Madonna for her music video of "Material Girl".

Cole and his subjects dance. Choreographer Chet Walker titled Heat Wave: The Jack Cole Project, given its world premiere in May 2012 at Queens Theatre in New York's Flushing Meadows Corona Park.[13][14]

"Jack changed musical theater," said Gwen Verdon, who worked both as his

assistant and as one of his dancers. If not for Cole, it is unlikely Gwen

Verdon would have gone on to achieve fame as a dancer; without his

instruction, many now-immortal stage and screen actresses probably would

not be remembered as dancers today.[12] "He is responsible for what we

call jazz today. He introduced ethnic dance. He influenced all the

choreographers in the theater from Jerome Robbins, Michael Kidd, Bob Fosse

down to Michael Bennett and Ron Field today. When you see dancing on

television, that's Jack Cole." Cole made just one picture for the Freed

unit: Kismet in 1955. He'd been set to choreograph for Ziegfeld Follies

but had offended Freed when he'd started denouncing studio politics at

Metro, gripping about all the "queen bees" like

Cedric Gibbons and

Roger Edens. He was more at home

staging numbers on Broadway or in nightclubs, where his word was law. "He

didn't like Hollywood," said Vernon, "but that's where he could make his

money, where he could fill his coffers, as he used to say."

Early on, Cole had married and had a son, but like Minnelli, he tried to

pretend his earl life had never happened, except that Minnelli was trying

to forget the gay part and Cole the straight. "Jack never tried to hide

the fact that he wa gay," said Verdon. "Oh, no, never. There would have

been no reason to. Only his mother had no idea. I remember once, she was

visiting just before we all went onstage, and Jack was in his costume,

with all his jewels, and she looked at him, very innocently, and said,

"You look like something right out of a storybook. You look like a real

fairy!" Of course, we all laughed so hard at that, especially Jack, but

his mother didn't realize what she had said." Many who worked with Cole

had no idea he’d ever been married or was a father. Hal Schaefer heard

about it only obliquely. After years as a touring bachelor musician, he

was thinking of marrying and settling down. He asked Cole’s advice.

Schaefer remembers, ‘He said, ‘I was married once.’ He said it was the

wrong life-style for him. But he had to live that way with a woman to see

if it would work out.”” Anna Austin Crane believes Cole married a girl he

knew in high school, in South Orange, New Jersey, around 1934, after which

a son, Maximilian, was born in 1935. Tragically, Cole’s young wife died in

childbirth. Austin says she had a letter—now lost—in which Cole had

written her the sad details. Because of Cole’s constant touring and

working in nightclubs, it wasn’t possible for him to raise the boy, so he

was cared for by the maternal grandparents. Later, the boy married and had

two sons, of whom Cole was very proud. Cole used to show Austin their

photos and talk about them. Apparently Cole did what he could financially

to help his son and his grandchildren. One Cole colleague remembers Cole

speaking of his son as: “My son, the accountant!” But he doesn’t know

whether that meant the son was actually an accountant. Austin says she has

not been able thus far to establish contact with Cole’s descendants. She

also notes that Cole said that at the time he never told his own mother

about his marriage.

Off the lot, he found the climate more to his liking, living in a fabulous

mansion on Kew Drive in Los Angeles with his lover,

David Gray (Gray was an actor and they met around 1937, together until

Cole's death), where they hosted

"very naughty and very gay" poolside parties, according to

Miles White. "I have this image

in my mind," said White, "of David Gray up on the diving board, getting

ready to jump off, and he's wearing high heels."

Working on The Merry Widow (1952), he "tried to capture the soft, gay

atmosphere of another century," but was stymied when the studio insisted

on bright lights for all the dance numbers. There are few moments as

simple and erotic as Rita Hayworth removing her gloves in her sinewy

rendition of "Put the Blame on Mame" in Gilda. "Provocative, if not

downright hot," said Motion Picture Herald. In Kismet, his one Freed film,

directed by Minnelli, critic Arthur Knight said Cole's "energetic,

angular, pseudo-Oriental routines possess a wit and urbane sureness, a

cleanness and precision visible nowhere else in this handsome, heavy and

stupendously dull production." In The I Don't Care Girl, slinky cat men in

black tights steal much of the erotic impact from Mitzi Gaynor's entrance.

At least one of the male dancers in that film,

Marc Wilder (he catches Mitzi

after a back somersault), was gay; he appeared in a number of Cole's shows

and also in several films (Meet Me in St. Louis, Can-Can.) For gay

auciences, the classic Cole number remains "Is There Anyone Here For

Love?" featuring Jane Russell and a gymnasium full of body-builders in

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). Cole's other numbers in the movie push

the envelope as well. Marilyn Monroe's "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend"

is set up like an orgy, with a vivid red background and women forming a

human chandelier. Cole was close with Monroe, who came to rely on him not

only as dance director but as personal guru. Anxious about the musical

numbers in There's No Business Like Show Business, she requested that Cole

handle her solos instead of Robert Alton, the film's official

choreographer. Monroe became increasingly dependent on him, insisting on

Cole's input even when he wasn't credited (Some Like It Hot) and

conferring with him more frequently than with director

George Cukor in Let's Make Love.

At the end of his life he was a dance teacher a the UCLA (University of California Los Angeles). Gray and Cole lived there from 1943 until Cole's death from cancer at 62 in 1974. Gray inherited Coles estate.

Gray died several months after the November 1979 auction of some of Jack Coles memorabilia, which was held at Sotheby's Auction House in London England.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

-

Jack Cole (choreographer) - Wikipedia

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

- Behind the Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood,

1910-1969, William J. Mann, 2001

- Unsung Genius, The Passion of Dancer-choreographer Jack Cole, By

Glenn Meredith Loney · 1984

Jack Cole (April 27, 1911 – February 17, 1974) was an American dancer, choreographer, and theatre director known as "the Father of Theatrical Jazz Dance".[1]

Producer Arthur Freed, who was not gay, never had as his purpose the

creation of a team of gay artists for MGM, nor were all the members of the

Arthur Freed unit gay. Freed did want a first-rate team, however, and

hired without regard to sexual orientation. A large number of the gifted

people on it turned out to be gay, including composers

Cole Porter,

Frederick Loewe,

Robert Wright, and

Chet Forrest, choreographers

Robert Alton and

Jack Cole, and directors

Charles

Walters and the closeted Vincente Minnelli.

Influential gay choreographers included Charles Walters, Robert Alton and

Jack Cole (who created Jane Russell’s number with the massed body-builders

in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes).

Jack Cole (April 27, 1911 – February 17, 1974) was an American dancer, choreographer, and theatre director known as "the Father of Theatrical Jazz Dance".[1]

Producer Arthur Freed, who was not gay, never had as his purpose the

creation of a team of gay artists for MGM, nor were all the members of the

Arthur Freed unit gay. Freed did want a first-rate team, however, and

hired without regard to sexual orientation. A large number of the gifted

people on it turned out to be gay, including composers

Cole Porter,

Frederick Loewe,

Robert Wright, and

Chet Forrest, choreographers

Robert Alton and

Jack Cole, and directors

Charles

Walters and the closeted Vincente Minnelli.

Influential gay choreographers included Charles Walters, Robert Alton and

Jack Cole (who created Jane Russell’s number with the massed body-builders

in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes).

.jpg)