Partner Florence Reynolds, Margaret Anderson, Elspeth Champcommunal

Queer Places:

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 116 S Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60603, Stati Uniti

27 W 8th St, New York, NY 10011

24 W 16th St, New York, NY 10011, Stati Uniti

44 Rue Jacob, 75006 Paris, France

36 Hamilton Terrace, London NW8, UK

East Finchley Cemetery, 122 E End Rd, London N2 0RZ, Regno Unito

Jane

Heap (November 1, 1883 – June 18, 1964) was an American publisher and a

significant figure in the development and promotion of literary modernism.

Together with

Margaret Anderson, her friend and business partner (who for some years was

also her lover), she edited the celebrated literary magazine The Little

Review, which published an extraordinary collection of modern American,

English and Irish writers between 1914 and 1929. Heap herself has been called

"one of the most neglected contributors to the transmission of modernism

between America and Europe during the early twentieth century."[1]

Jane’s pithy pronouncements were legendary. She famously called the Paris

publisher Robert McAlmon “an

epileptic without gumption enough to have fits” and said that Burton Rascoe,

literary editor of the Herald Tribune, “wouldn’t have recognized the Sphinx

outside of Egypt.” Once, paying tribute to someone who had (briefly)

understood her, Jane remarked: “A hand on the exact octave that is me.”

Another time, responding to Margaret’s cry that “life should be ecstasy,” Jane

laconically replied, “Why limit me to ecstasy?”

Jane

Heap (November 1, 1883 – June 18, 1964) was an American publisher and a

significant figure in the development and promotion of literary modernism.

Together with

Margaret Anderson, her friend and business partner (who for some years was

also her lover), she edited the celebrated literary magazine The Little

Review, which published an extraordinary collection of modern American,

English and Irish writers between 1914 and 1929. Heap herself has been called

"one of the most neglected contributors to the transmission of modernism

between America and Europe during the early twentieth century."[1]

Jane’s pithy pronouncements were legendary. She famously called the Paris

publisher Robert McAlmon “an

epileptic without gumption enough to have fits” and said that Burton Rascoe,

literary editor of the Herald Tribune, “wouldn’t have recognized the Sphinx

outside of Egypt.” Once, paying tribute to someone who had (briefly)

understood her, Jane remarked: “A hand on the exact octave that is me.”

Another time, responding to Margaret’s cry that “life should be ecstasy,” Jane

laconically replied, “Why limit me to ecstasy?”

Heap was born in Topeka, Kansas, where her father, George Heap, worked as an "engineer" at the Insane Asylum (later known as the Topeka State Hospital). Jane Heap graduated from Topeka High School on May 28, 1901. In October 1901, at the age of 17, she enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago. She later became a student at the Lewis Institute in Chicago, where Marie Blanke became her mentor, close friend and lover. Marie Blanke and Heap organized and operated "Blanke and Heap's Nickel Theatre" at the Lewis Institute. Marie Blanke was the "James" to whom Jane Heap refers in her letters to Reynolds in 1908-1909. Jane Heap met Florence Reynolds through Marie Blanke's "Chicago group," a circle of friends which included Esther Blanke (Marie's sister), Florence Reynolds, Elsa Koop, and Olive Garnet. The "Chicago group" was comprised of young women from affluent families who shared an interest in the arts.

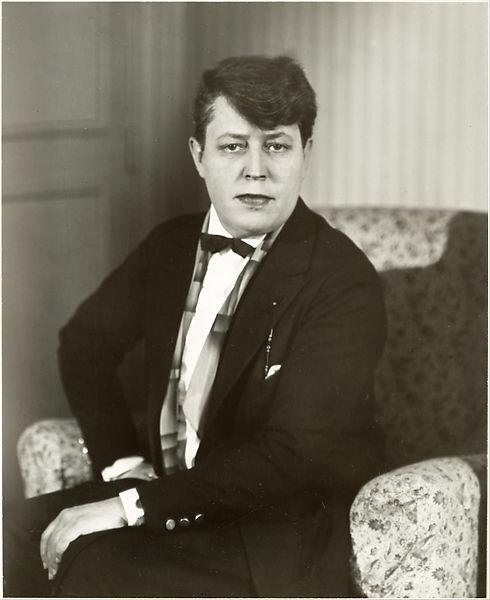

Jane Heap ca. 1928 by Berenice Abbott

Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, middle standing; Ezra Pound, right

standing; Man Ray, with camera; Mina Loy, front center; Tristan Tzara, to her

right; and Jean Cocteau, with cane; in Paris

Tristan Tzara (second from right) in the 1920s, with Margaret C. Anderson, Jane Heap, and John Rodker

.jpg)

Studebaker Building/Fine Arts Building, 410-418 S Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL 60605

24 W 16th St

Reynolds and Heap became lovers, in 1910 travelling together to Germany, where Heap studied tapestry weaving. The two women remained friends throughout their lives, although they often lived apart, and despite the fact that Heap formed romantic attachments with many other women.[2][3]

As an artist, Jane Heap received recognition for her watercolor drawings. In a 1911 Chicago Tribune review of an exhibition which included Heap's work, Harriet Monroe favorably mentioned Jane Heap's watercolors. An article in the December 15, 1915 issue of the Topeka Capital noted that Heap had established a studio in Chicago and had received several commissions for murals. Heap also designed scenery and costumes for Maurice Brown's "Little Theatre" in Chicago, as well as acting in their productions.

In 1912, Heap helped found Maurice Browne's Chicago Little Theatre, an influential avant-garde theatre group presenting the works of Chekhov, Strindberg and Ibsen and other contemporary works.

Around 1915, Jane Heap met and became intricately involved in the life of Margaret Anderson, creator and editor of The Little Review. Jane Heap's first appearance as a writer occurred in the June-July 1915 issue of The Little Review, with a review titled "The Nine." Heap used a number of pseudonyms, such as "R" and "Garnerin" and signed many contributions with the nearly anonymous "jh." During the final years of The Little Review Heap was the primary editor and indeed it was she, not Margaret Anderson, who wrote the farewell editorial for the magazine.

The Little Review played a leading role in the literary modernism of the 1920s. The magazine's regular contributors included Sherwood Anderson, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and William Carlos Williams. Anderson and Heap published relative unknowns such as Hart Crane, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Ford Maddox Ford. In addition to featuring young American expatriates living in Paris, The Little Review introduced readers to numerous European authors and artists, including Francis Picabia, Juan Gris, Fernand Leger, Remy de Gourmont, and Constantin Brancusi.

In February 1916 the he Little Review was now two years old and Margaret Anderson had just moved back to downtown Chicago, her lakefront interlude having come to a close. One day an heiress whom Margaret had impishly dubbed Nineteen Millions (Aline Barnsdall) was visiting the magazine offices. Margaret, of course, was hoping that her wealthy guest might be willing to part with a few pennies in the interest of “Art.” The courtship was well under way. Minutes earlier, Jane Heap had come in. A perfect stranger, she stood quietly to the side, big-boned and imposing, listening as Nineteen Millions spouted opinions. Jane watched with interest. Finally, letting out a tender laugh, she interjected a wry observation. Nineteen Millions glared at Jane with fury. Then she abruptly stomped out, muttering that, above all things, she “disliked frivolity.” Margaret’s reaction was just the opposite. She knew instantly that she wanted to live with this kind of frivolity forever. All that spring Margaret had been casting about for a housing solution to the summer. One day it occurred to her that Nineteen Millions had extended an open invitation to visit her in California. Margaret wrote immediately to say she was coming—she and her “helpmate” Jane Heap—choosing to overlook the minor matter of their earlier spat. Nineteen Millions was less forgetful. Margaret was of course welcome, she wrote; Jane Heap was emphatically not. Undeterred, Margaret insisted they go anyway. Though this time it was Margaret who stomped out in a huff, only moments after Nineteen Millions had pronounced Jane “odious” for a second time. Margaret never doubted their luck would turn.

In 1917 Anderson and Heap moved The Little Review to New York, and with the help of critic Ezra Pound, who acted as their foreign editor in London, The Little Review published some of the most influential new writers in the English language, including Hart Crane, T. S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Pound himself, and William Butler Yeats. The magazine's most published poet was New York dadaist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, with whom Heap became friends on the basis of their shared confrontational feminist and artistic agendas.[5] Other notable contributors included Sherwood Anderson, André Breton, Jean Cocteau, Malcolm Cowley, Marcel Duchamp, Ford Madox Ford, Emma Goldman, Vachel Lindsay, Amy Lowell, Francis Picabia, Carl Sandburg, Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, Arthur Waley, and William Carlos Williams. Even so, however, they once published an issue with 12 blank pages to protest the temporary lack of exciting new works.

In March 1918, Ezra Pound sent them the opening chapters of James Joyce's Ulysses, which The Little Review serialized until 1920, when the U.S. Post Office seized and burned four issues of the magazine and convicted Anderson and Heap on obscenity charges. Although the obscenity trial was ostensibly about Ulysses, Irene Gammel argues that The Little Review came under attack for its overall subversive tone and, in particular, its publication of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's sexually explicit poetry and outspoken defense of Joyce.[6] The Baroness paid tribute to Jane Heap's combative spirit in her poem "To Home," which is dedicated to "Fieldadmarshmiralshall/ J.H./ Of Dreadnaught:/ T.L.R."[7] At their 1921 trial, they were fined $100 and forced to discontinue the serialization. Following the trial, Heap became the main editor of the magazine, taking over from Anderson, and introducing brightly coloured covers and experimental poetry from surrealists and Dadaists.[8]

At about the same time, the Little Review editors accepted their first story by Djuna Barnes, beginning an uneasy friendship that, in Margaret Anderson’s words, “might have been great had it not been that Djuna always felt some fundamental distrust of our life—of our talk.” Margaret had initially been taken by the tall, dashing Djuna, with her mordant wit and elegant voice, her trill of sharp laughter. She was moved by Djuna’s maternal side. “You two poor things,” Djuna would say in her warm, laughing voice. “You’re both crazy of course, God help you. I suppose I can stand it if you can, but someone ought to look out for you.” Djuna looked out for them by bringing in the first strawberries of spring and the last oysters of winter, said Margaret, “but to the more important luxuries of the soul she turned an unhearing ear. Djuna would never talk. . . . She said it was because she was reserved about herself. She wasn’t, in fact, reserved—she was unenlightened.” On Djuna’s part, she viewed Margaret with wary respect. Though she mocked Margaret’s fastidiousness, saying that she even washed her soap before using it, decades later, recalling Margaret in a letter, she wrote: “In her young years I never thought her very good-looking, as many people did, but now she is beautiful—I mean it really. Her serious face is beautifully tragic and her smile has the loveliest, most touching charm.” Later Margaret would accuse Djuna of having an “outside that was often stunning” and an inside that she didn’t know anything about. Margaret said it embarrassed her “to attempt a relationship with anyone who was not on speaking terms with her own psyche.” The truth was more complicated. The seed of Margaret’s hostility was sown, no doubt, by an affair rumored to have taken place between Djuna and Jane Heap sometime between 1918 and 1919. The only witness to the full fury produced by the incident comes in a short passage from the memoirs of the artist Maurice Sterne, Mabel Dodge’s third husband and briefly one of Barnes’s lovers. As Sterne remembered: I had dinner with Djuna Barnes, the avant-garde writer, occasionally. She ordinarily spoke very little, being more interested in observing the people she was with. One night at Polly’s restaurant in Greenwich Village, Djuna suddenly exclaimed that she saw someone she knew. She took me over to a table where a mousy girl was dining with some friends. Djuna began hissing,—hate you, I hate you, I hate you over and over again. The tan mouse smiled sweetly but there was an electric spark in her smile and they had an ominously quiet, violent fight before Djuna stalked out with that long stride of hers. The “mouse” was Margaret Anderson and the matter in dispute was her lover Jane. Djuna’s letters to another friend, written sometime in 1938, refer to Jane Heap as a “shit,” perhaps indicating that the affair ended badly.

Heap met G. I. Gurdjieff during his 1924 visit to New York, and was so impressed with his philosophy that she set up a Gurdjieff study group at her apartment in Greenwich Village. In 1925, she moved to Paris, to study at Gurdjieff's Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, where Margaret Anderson had moved the previous year alongside her new lover, soprano Georgette Leblanc. Although they now lived separately, Heap and Anderson continued to work together as co-editors of The Little Review until deciding to close the magazine in 1929. Heap also at this time adopted Anderson's two nephews, after Anderson's sister had had a nervous breakdown, and Anderson herself had shown no interest in becoming a foster mother.

Heap established a Paris Gurdjieff study group in 1927, which continued to grow in popularity through the early 1930s, when Kathryn Hulme (author of The Nun's Story) and journalist Solita Solano (Sarah Wilkinson) joined the group. This developed into an all-women Gurdjieff study group known as "the Rope", taught jointly by Heap and by Gurdjieff himself.

Anderson and Heap moved The Little Review from Chicago for a brief time to Mill Valley, California, for a longer period to New York City, and finally to Paris where they were both living in the late 1920s. In New York, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heapwere exposed to the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff, an eastern philosopher who had fled post-czarist Russia and established the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at Fontainbleau outside of Paris. One of Gurdjieff's students, A.E. Orage, former editor of the London magazine New Age, had been sent to New York to introduce the Gurdjieffian teachings to Americans.

In 1928 Berenice Abbott took an iconic portrait of Heap.

Anderson and eventually Jane Heap pursued the teachings and moved to France. There was great transition in their lives during the 1920s as they moved to Paris; as Heap took over custody of Tom and Fritz Peters, the children of Anderson's institutionalized sister; as Anderson became the companion of Georgette LeBlanc, former companion and accompanist of Maurice Maeterlinck; and as finally, in 1929 they issued the last Little Review.

By the 1930s, Jane Heap had moved to London where she taught the Gurdjieffian philosophies to a new circle of students. Heap did not continue with any literary or creative ventures but devoted the rest of her life to teaching. Heap lived in London with Elspeth Champcommunal until her death on June 22, 1964. Florence Reynolds maintained her lifelong support of her friend Jane Heap with regular gifts, correspondence, visits, and the benefits of her final will.

In 1935, Gurdjieff sent Heap to London to set up a new study group. She would remain in London for the rest of her life, with her new partner, Elspeth Champcommunal, including throughout The Blitz. Her study group became very popular with certain sections of the London avant-garde, and after the war its students included the future theatre producer and director, Peter Brook.

Apart from her Little Review work, Heap never in her lifetime published an account of her ideas, although both Hulme and Anderson published collections of memoirs, and particularly their memories of working with Gurdjieff. After Heap's death from diabetes in 1964, former students put together a collection of her aphorisms (both her own and Gurdjieff's) and, in 1983, some notes reflecting her expression of some of the key Gurdjieff ideas. Some of her aphorisms are given below:[9]

In 2006 Heap and Margaret Anderson were inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame.[10]

My published books: