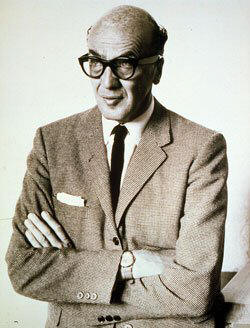

Partner José Limón

Queer Places:

Casa Estudio Luis Barragán, Gral. Francisco Ramírez 12, Ampliación Daniel Garza, Miguel Hidalgo, 11840 Ciudad de México, CDMX

Las Arboledas, 13219 Mexico City, CDMX, Mexico

Jardines del Pedregal, Primera Cerrada las Fuentes, Álvaro Obregón, 01900 Ciudad de México, CDMX, Mexico

Convento de las Capuchinas

Sacramentarias, Col. de, Miguel Hidalgo 43, Tlalpan Centro I, Tlalpan, 14000 Ciudad de México, CDMX

Jardines del Bosque, Av Paseo de la Arboleda, 44520 Guadalajara, Jal., Mexico

Torres de Satélite, Ciudad Satélite, 53100 Naucalpan de Juárez, State of Mexico, Mexico

Lomas Verdes, Pierre Lyonett, 53120 Naucalpan de Juárez, Méx., Mexico

Cuadra San Cristóbal, Los Clubes, Cda. Manantial Ote. 20, Mayorazgos de los Gigantes, 52957 Cd López Mateos, Méx., Mexico

Gilardi House, Calle Gral. Antonio León 82, San Miguel Chapultepec I Secc, Miguel Hidalgo, 11850 Ciudad de México, CDMX, Mexico

Cuernavaca Racquet Club, Francisco Villa No. 100, Santa María Ahuacatitlán, 62100 Cuernavaca, Mor., Mexico

Casa Cristo, C. Pedro Moreno 1612, Col Americana, Lafayette, 44160 Guadalajara, Jal., Mexico

Luis Ramiro Barragán Morfín (March 9, 1902 – November 22, 1988) was a Mexican architect and engineer. His work has influenced contemporary architects visually and conceptually.[1] Barragán's buildings are frequently visited by international students and professors of architecture. He studied as an engineer in his home town, while undertaking the entirety of additional coursework to obtain the title of architect.[2]

Barragán won the Pritzker Prize, the highest award in architecture, in 1980, and his personal home, the Luis Barragán House and Studio, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.[11] In 2019, "Uncovering the Sexuality and Solitude of a Modern Mexican Icon",

a provocative exhibition at Casa Luis Barragán, reframed the architect’s home and studio through his class and gay identity.

Luis Ramiro Barragán Morfín (March 9, 1902 – November 22, 1988) was a Mexican architect and engineer. His work has influenced contemporary architects visually and conceptually.[1] Barragán's buildings are frequently visited by international students and professors of architecture. He studied as an engineer in his home town, while undertaking the entirety of additional coursework to obtain the title of architect.[2]

Barragán won the Pritzker Prize, the highest award in architecture, in 1980, and his personal home, the Luis Barragán House and Studio, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.[11] In 2019, "Uncovering the Sexuality and Solitude of a Modern Mexican Icon",

a provocative exhibition at Casa Luis Barragán, reframed the architect’s home and studio through his class and gay identity.

Barragán was an observant Catholic and closeted gay man; discreet crosses appear throughout the house, in window-cladding or above door jambs. Unlike the 'Glass House' of his closeted contemporary, Philip Johnson, Casa Barragán is a black box of privacy, more akin to a priest’s confessional than a fishbowl. ‘Thanks to a singular strategy for walls,’ the historian Juan Acha once observed, ‘every liveable space begins to revolve around itself and irradiates a convent-like solitude that invites introspection and withdrawal.’ Though Barragán was a famous host, his home has since his death acquired a monastic pink aura.

Jesus ‘Chucho’ Reyes was a closeted Catholic and friend of Barragán’s. In the house, two long ink paintings on paper by Reyes are in the architect’s bedroom, both depicting a flagellated Christ in a style redolent of Japanese ukiyo-e. Jesús Reyes fled Guadalajara in 1938 after being arrested during a raid at a private gathering in his own home being accused of “indecency”—a term used to define alleged homosexual activities. After being beaten by the police and humiliated publicly, Reyes decided to sell his childhood home in Guadalajara and leave to the more progressive capital. Carlos Monsiváis, a recognized writer and journalist, also confirmed these details during a public event inaugurating a museum in Guadalajara in 2008, claiming that Jesús Reyes’s homosexuality and sexual preference was the same as that of other renowned men from Jalisco who at the time no longer lived in Guadalajara, naming various figures (however, not Barragán) who moved to Mexico City at the end of 1935.

Sexuality and solitude resurface in another painting, Mientras me despierto (As I Wake Up, 1985) by Julio Galán. The painting depicts a young man with a sweeping cape peering out a small orange window. Pale bloodied hands claw at the edges of his emerald prison, where a sinister Dalmatian in boxer shorts wags a steak knife. Galán’s own openness as a gay man did not mean he felt any freer in his hometown of Monterrey. A tiny window beside the painting lets just a sliver of light into the room where it hangs, slyly moulded by cruciform shutters.

Miguel Covarrubias and Rosa Rolanda were Zeligs of Mexican modernism: the husband and wife painter-choreographer pair crop up in almost all of the movement’s primal scenes. Covarrubias and Rolanda introduced Barragán to the dancer José Limón, his erstwhile lover, who poses on black volcanic rocks in a series of photographs that rest on a living room lectern. They were taken at El Pedregal, a gated development Barragán designed, and whose fusion of modern principles and hacienda architecture signalled Mexico City’s gentrification.

Luis Barragán set up his studio in Mexico City, the building is currently a museum, but with tours available only by appointment. The building is from 1948 reflecting Barragán's preferred style, where he lived his whole life. Today is owned by Jalisco and the Arquitectura Tapatía Luis Barragán Foundation.

Barragán was born in Guadalajara in Jalisco, Mexico. Educated as an engineer, he graduated from the Escuela Libre de Ingenieros in Guadalajara in 1923. After graduation, he traveled through Spain and France. While in France he became aware of the writings of Ferdinand Bac, a German-French writer, designer and artist whom Barragán cited throughout his life.[3] In 1931, he again traveled to France with a long stop-over in New York. In this trip he met Mexican mural painter José Clemente Orozco, architectural magazine editors, and Frederick Kiesler. In France he briefly met Le Corbusier and finally visited the gardens realized by Ferdinand Bac. He practiced architecture in Guadalajara from 1927–1936, and in Mexico City thereafter.

His Guadalajara work includes over a dozen private homes in the Colonia Americana area of what is today near downtown Guadalajara. These homes, within walking distance of each other, include Barragán's earliest residential projects. One of his first buildings, Casa Cristo, was restored and houses the state's Architects' Guild.

The structure and design of homes answered gay households’ needs, such as a ‘modern residence for a family consisting of two persons’ advertised in 1937. Projected for an urban lot of 225 square metres, it featured a small front garden and carport, a dining room, a living room, a kitchen with butler’s pantry, a breakfast nook on the ground floor and a guest powder room. The main stairwell led to the bathroom, a small hall or den, two bedrooms, a library and a sewing room. A metal spiral staircase in the kitchen led to separate servants’ quarters on the second floor, but their rooms did not connect at all to those of the homeowners on the same floor, on the other side of the bathroom wall. Such designs guaranteed gay couples privacy – and a spare bedroom for visitors. The isolation of the master bedroom from the rest of the house, with an en-suite bathroom, facilitated pre- and post-coital hygiene. The library and sewing room offered couples separate home workspaces, or perhaps a studio for artists. Native and foreign designers decorated these modern residences. Sophisticated, natural, organic design elements incorporated elements of Frank Lloyd Wright’s prairiestyle architecture – particularly in the homes society architect Jorge Rubio built – but also went well with Luis Barragán’s minimalist landscape projects. The furnishings of designers like Cuban-born Clara Porset and American expatriates Michael Van Beuren and Emmett Morley Webb allowed apartment owners to incorporate a modern aesthetic into their domestic spaces that rejected the ornate historicist aesthetics of Porfirian furnishings or the rough-hewn, quaint furniture of rural folk. Modern style thus represented the values and stability to which the middle class aspired, and offered clean lines and high-quality natural finishes. Gay interior designers such as Arturo Pani (with Jay de Laval) and Webb were also in great demand among the gay elite. Posh gays competed to outdo each other in their homes’ expressions of originality, taste and elegance. Composer Gabriel Ruiz and physician Elías Nandino constantly re-upholstered and reappointed their homes, fighting over the best tradesmen and decorators; Nandino’s one-upmanship went so far as to use fishbowls – with live fish – as lampshades.

In 1945 Barragán started planning the residential development of Jardines del Pedregal, Mexico City. In 1947 he built his own house and studio in Tacubaya and in 1955 he rebuilt the Convento de las Capuchinas Sacramentarias in Tlalpan, Mexico City, and the plan for Jardines del Bosque in Guadalajara. In 1957 he planned Torres de Satélite (an urban sculpture created in collaboration with sculptor Mathias Goeritz) and an exclusive residential area, Las Arboledas, a few kilometers away from Ciudad Satélite. In 1964 he designed, alongside architect Juan Sordo Madaleno, the Lomas Verdes residential area, also near the Satélite area, in the municipality of Naucalpan, Estado de México. In 1967 he created one of his best-known works, the San Cristóbal Estates equestrian development in Mexico City.

Barragán visited Le Corbusier and became influenced by European modernism. The buildings he produced in the years after his return to Mexico show the typical clean lines of the Modernist movement. Nonetheless, according to Andrés Casillas (who worked with Barragán), he eventually became entirely convinced that the house should not be "a machine for living." Opposed to functionalism, Barragán strove for an "emotional architecture" claiming that "any work of architecture which does not express serenity is a mistake." Barragán used raw materials such as stone or wood. He combined them with an original and dramatic use of light, both natural and artificial; his preference for hidden light sources gives his interiors a particularly subtle and lyrical atmosphere.

Barragán worked for years with little acknowledgement or praise until 1975 when he was honored with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In 1980, he became the second winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Barragán died at the age of eighty-six in Mexico City. In his will, he designated three people to manage his legacy: Ignacio Díaz Morales, Óscar González González, and Raúl Ferrera.[5] Ignacio Díaz Morales, a friend and fellow architect, was bequeathed Barragán's library. He was tasked with choosing an institution suitable for receiving the book collection. Óscar Ignacio González, a childhood friend, received Barragán's personal objects. Raúl Ferrera, his business partner, received the archives and the copyright to the work. Díaz Morales established the Fundación de Arquitectura Tapatía, a private foundation managed by the Casa Barragán, in co-ownership with the Government of the State of Jalisco. The house is now a museum which celebrates Barragán and serves as a conduit between scholars and architects interested in visiting other Barragán buildings in Mexico.[6] Following Raúl Ferrera's passing away in 1993, the archives and related copyright became the property of Ferrera's widow who, after having unsuccessfully tried to find a collector or institution willing to keep these in Mexico, decided to sell them to the Max Protetch Gallery in New York. The documents were offered to a number of prospective clients, among them the Vitra Design Museum,[8] which in 1994 was planning an exhibition dedicated to Luis Barragán. Following the Vitra[9] company's policy of collecting objects and archives of design and architecture, the archives were finally acquired in their entirety and transferred to the Barragán Foundation in Switzerland. The Barragan Foundation[10] is a not-for-profit institution based in Birsfelden, Switzerland. Since 1996, it manages the archives of Luis Barragán, and in 1997 acquired the negatives of the photographer Armando Salas Portugal documenting Barragán's work. The Foundation's mission is to spread the knowledge on Luis Barragán's cultural legacy by means of preserving and studying his archives and related historical sources, producing publications and exhibitions, providing expertise and assistance to further institutions and scholarly researches. The Barragán Foundation owns complete rights to the work of Luis Barragán and to the related photos by Armando Salas Portugal.

My published books: