Partner Geraldine Thompson,

Anna Spicer Gladding

Queer Places:

Clark University, 950 Main St, Worcester, MA 01610, USA

1833 N Verdugo Rd, Glendale, CA 91208, USA

Pine Hill Cemetery, Sherborn, Massachusetts 01770, Stati Uniti

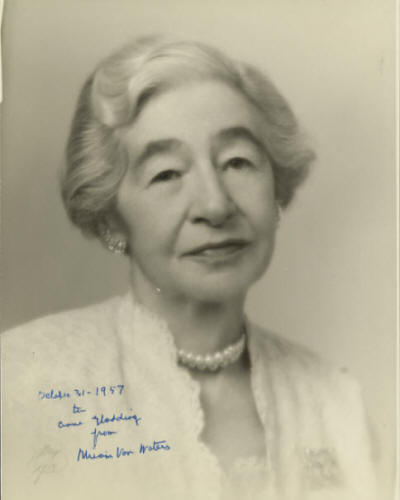

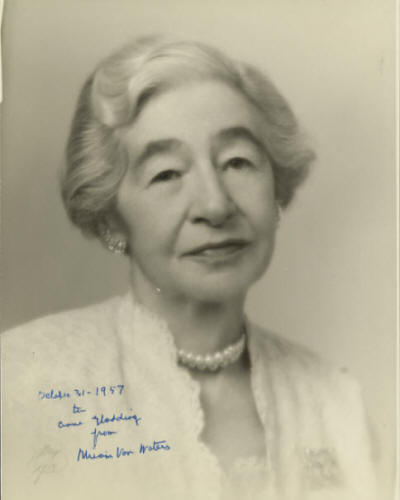

Miriam

Van Waters (October 4, 1887 – January 17, 1974) was an American prison

reformer of the early to mid-20th century whose methods owed much to her

upbringing as an Episcopalian involved in the Social Gospel movement.

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior designer

Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. Van Waters was

superintendent of the Reformatory for Women in Framingham, Mass. (1932-1957).

Her liberal views on penal reform brought her both praise and condemnation. In

January 1949 she was fired because of alleged administrative failings, such as

condoning lesbianism among the "students" (as she called the prisoners) and

failing to supervise a work-release program properly. After a lengthy hearing

process she was reinstated. Van Waters was the author of Youth in Conflict

(1925) and Parents on Probation (1927). Van Waters also served as director of

El Retiro (1919-1920), a school for delinquent girls in California, referee

for the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court (1920-1930), consultant for the

Wickersham Commission (1928-1931), and on a number of other boards and

commissions.

Miriam

Van Waters (October 4, 1887 – January 17, 1974) was an American prison

reformer of the early to mid-20th century whose methods owed much to her

upbringing as an Episcopalian involved in the Social Gospel movement.

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior designer

Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. Van Waters was

superintendent of the Reformatory for Women in Framingham, Mass. (1932-1957).

Her liberal views on penal reform brought her both praise and condemnation. In

January 1949 she was fired because of alleged administrative failings, such as

condoning lesbianism among the "students" (as she called the prisoners) and

failing to supervise a work-release program properly. After a lengthy hearing

process she was reinstated. Van Waters was the author of Youth in Conflict

(1925) and Parents on Probation (1927). Van Waters also served as director of

El Retiro (1919-1920), a school for delinquent girls in California, referee

for the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court (1920-1930), consultant for the

Wickersham Commission (1928-1931), and on a number of other boards and

commissions.

In 1932,

Anna Spicer Gladding

began a 42-year association with the Reformatory for Women in Framingham,

Mass., where she was involved in the mother-child program and served as prison

librarian, organist and choir director, and leader of the literary and nature

study clubs. Her partner, Miriam Van Waters, was superintendent of the

Reformatory for Women (1932-1957). Van Waters’s liberal views on penal reform

brought her both praise and condemnation.

Historian Estelle Freedman records the terse diary entry, “The burning of

letters continues,” which alerted her to pioneer prison superintendent Miriam

Van Waters's erasure of her correspondence with her beloved friend Geraldine Thompson.

Miriam Van Waters, who formed a deeply romantic relationship with her

benefactor Geraldine Thompson, herself a married woman, struggled with the

definition of being lesbian. In the 1920s, when the two women first met, the

concept of homosexuality was no mystery, and Van Waters had read the work of

the sexologists. But “lesbianism” suggested gender inversion, the “mannish”

lesbian, or a Freudian notion of pathology, and Miriam and Geraldine

considered themselves “normal.” Yet they were also careful to conceal their

relationship in certain situations, and Van Waters expressed doubt about her

own sexuality. When Van Waters later came under attack for tolerating

homosexuality at the women's prison she supervised, she and Thompson

systematically burned their letters. Van Waters did not consider her

relationship with Thompson in the same category as the lesbianism among prison

inmates, but she was afraid others would.

During

her career as a penologist, which spanned most of the years from 1914 through

1957, Van Waters served as superintendent of three prisons: Frazier Detention Home

for boys and girls in Portland, Oregon; Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall for

girls, and the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women at Framingham. While in

California, Van Waters established an experimental reformatory school, El

Retiro, for girls age 14 to 19. In each case, Van Waters developed programs

that favored education, work, recreation, and a sense of community over

unalloyed incarceration and punishment.

Born in Pennsylvania, she grew up in Portland after her father, a clergyman

and Social Gospel advocate, accepted a position there as rector of St. David's

Episcopalian Church. As the eldest daughter of an ailing mother, she often

served as a surrogate mother, as she did later as a supervisor of imprisoned

women and children. Her first crush was at 15, a girl named Genevieve, who she

declared her soulmate. Genevieve eventually moved to Greenwich Village. After graduating from secondary school, Van Waters

attended the University of Oregon, majoring at first in philosophy and

graduating in 1910 with a master's degree in psychology. At Oregon, Van Waters

had a mostly female circle of friends and at least one of these blossomed into

a romantic relationship. Three years later, at

Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, she completed a doctorate in

anthropology.

Van Waters' public-speaking skills, assertive manner, and charisma drew

national as well as local attention to her methods, and she was supported

financially by philanthropists including Ethel Sturges Dummer, who helped pay

for El Retiro and for leaves of absence from her supervisory duties to work on

two books, Youth in Conflict (1925) and Parents on Probation

(1927). Another wealthy philanthropist,

Geraldine Morgan Thompson, supported Van Waters financially and

emotionally from the mid-1920s until Thompson's death in 1967.

Eleanor

Roosevelt, a first lady, and Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard law professor

and then a Supreme Court justice, were among Van Waters' many admirers and

political supporters, but her methods drew the ire of opponents who viewed

them as over-lenient and ineffective. Opposition in Los Angeles led to her

departure from California in 1932 and to much-publicized hearings in

Massachusetts after she was fired as Framingham superintendent in January

1949. Re-instated in March, she continued running the reformatory until 1957.

After retiring, she remained in the town of Framingham, living in a

woman-centered household, as she had often done, until her death in 1974.

In the 1920s Orfa Jean Shontz, Van

Waters, Van Waters' friends Sara Fisher

and Emily "Pole" Reynolds, a

teacher of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and

Elizabeth "Bess" Woods, founder

of the educational-research department for the Los Angeles Board of Education,

all lived in a group of residences called the Colony, between Los Angeles and

Pasadena. When the Colony burned down, Van Waters, Woods, and Shontz rented a

house in Glendale that they called the "Stone House".[5]

During the latter half of the decade, Van Waters entered what was to be a

strong, eventually intimate 40-year relationship with another wealthy

philanthropist, Geraldine Morgan Thompson,

who supported prison reform in her home state of New Jersey and elsewhere.

Encouraged by Thompson, Dummer, and Frankfurter, Van Waters relocated to

Cambridge in 1931.

In that same year, publication of her 175-page Wickersham Commission report,

The Child Offender in the Federal System of Justice, enhanced her

reputation as an expert on juvenile justice.

After declining a job offer from Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot, as an

administrator in the state welfare department, she learned in November that

she would soon be offered the position of superintendent at the Massachusetts

Reformatory for Women at Framingham, replacing Jessie Donaldson Hodder, who

had recently died.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miriam_Van_Waters

- Rupp, Leila J.. A Desired Past (p.14). University of

Chicago Press. Edizione del Kindle.

- Ferentinos, Susan,. Interpreting LGBT History at

Museums and Historic Sites (Interpreting History) . Rowman &

Littlefield Publishers. Edizione del Kindle.

-

Improper Bostonians Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to

Playland By History Project Staff · 1998

-

The Hub of the Gay Universe, An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown, and

Beyond, by Russ Lopez, 2019

-

Rupp, Leila J.. Sapphistries (Intersections) (p.156). NYU Press. Edizione

del Kindle.

-

Home -

LGBTQ - Research Guides at Harvard Library

-

Miriam Van Waters | Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard

University

Miriam

Van Waters (October 4, 1887 – January 17, 1974) was an American prison

reformer of the early to mid-20th century whose methods owed much to her

upbringing as an Episcopalian involved in the Social Gospel movement.

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior designer

Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. Van Waters was

superintendent of the Reformatory for Women in Framingham, Mass. (1932-1957).

Her liberal views on penal reform brought her both praise and condemnation. In

January 1949 she was fired because of alleged administrative failings, such as

condoning lesbianism among the "students" (as she called the prisoners) and

failing to supervise a work-release program properly. After a lengthy hearing

process she was reinstated. Van Waters was the author of Youth in Conflict

(1925) and Parents on Probation (1927). Van Waters also served as director of

El Retiro (1919-1920), a school for delinquent girls in California, referee

for the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court (1920-1930), consultant for the

Wickersham Commission (1928-1931), and on a number of other boards and

commissions.

Miriam

Van Waters (October 4, 1887 – January 17, 1974) was an American prison

reformer of the early to mid-20th century whose methods owed much to her

upbringing as an Episcopalian involved in the Social Gospel movement.

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior designer

Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. Van Waters was

superintendent of the Reformatory for Women in Framingham, Mass. (1932-1957).

Her liberal views on penal reform brought her both praise and condemnation. In

January 1949 she was fired because of alleged administrative failings, such as

condoning lesbianism among the "students" (as she called the prisoners) and

failing to supervise a work-release program properly. After a lengthy hearing

process she was reinstated. Van Waters was the author of Youth in Conflict

(1925) and Parents on Probation (1927). Van Waters also served as director of

El Retiro (1919-1920), a school for delinquent girls in California, referee

for the Los Angeles County Juvenile Court (1920-1930), consultant for the

Wickersham Commission (1928-1931), and on a number of other boards and

commissions.