Partner E.M. Forster

Queer Places:

Mansoura, Mansoura Qism 2, El Mansoura, Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt

For

most critics the central event of

E.M. Forster’s life in

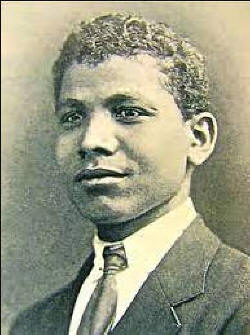

Alexandria was his intimate relationship with Mohammed el-Adl (1900 -

May 8, 1922), an Arab Egyptian.

For

most critics the central event of

E.M. Forster’s life in

Alexandria was his intimate relationship with Mohammed el-Adl (1900 -

May 8, 1922), an Arab Egyptian.

Born in the late nineteenth century, Mohammed El Adl grew up doubly subjected to the Ottoman Empire and British occupation. He lived his final years, between 1914 and 1922, in the intersections of the First World War and British colonialism. Arriving in Alexandria around the same time as Forster, he had grown up in Mansourah, a small town in the lower Nile delta. Although provincial, early-twentieth-century Mansourah was one of a number of Egyptian towns that had acquired importance as a regional center for the cotton export industry, and was as a consequence linked by railway to Alexandria. The character of pre-war Mansourah was a function of European interests in Egypt as a producer of raw cotton for export. El Adl’s identity and the nature of his war experience are shaped by these urban origins and their connection to colonialism.

On arriving in Alexandria he worked as a wage laborer on the trams, but inherited property from his father in 1918.

In the winter of 1916-1917, that is during World War I, E. M. Forster was in Alexandria, Egypt serving with the Red Cross. At Ramlah Station, near Alexandria, Forster met the 17 year old boy Mohammed el-Adl, a Muslim tram conductor. They fell in love and Forster enjoyed his first satisfactory sexual relationship. Unlike Forster, who never learned his lover’s native language, El Adl was sufficiently educated to write to Forster in English, and to hold a clerical position with the British military. His letters to Forster demonstrate considerable fluency and a self-consciousness about his level of literacy. From the canal zone he writes that “I can read all your letters easily. I think that my English is greatly improved for I spend all my time going with the Englishmen. I want you to correct my mistakes but not to blame me”.

As a town dweller El Adl was less likely to serve in the Egyptian army and protected from recruitment to the Egyptian Labour Corps, which drew largely from Egypt’s rural population. El Adl’s urban upbringing probably accounts too for his being partially secularized. He writes to Forster that, “Yes, I had kept Ramadan this year owing that my wife is very simple and is very pious” At the same time his letters suggest a strong religious affiliation, in for example, his insistence that Forster “Be sure that your religious opinions do not put me off you as you respect mine as I do yours . . . God has created everything on and beneath the globe”.

El Adl was able to use Forster’s social networks, which included Cambridge connections, the Red Cross, and the Army, to move from the trams to clerical work in the British army. As a clerical worker, El Adl earned significantly more and seemed to be on his way to middle-class status and economic security. However, the job came near to killing him: working in the restricted military zone of the Canal, El Adl was hospitalized for a minor illness, and nearly died because of the terrible conditions of native hospitals. His escape was largely due once again to Forster’s networks. Back home in Mansourah, he wrote Forster that “I am allright now, better than before I want to tell you how happy I will be if I found a job outside the Canal Zone and it will be better if it was not a military job”. Less understated in his reaction, Forster wrote to his friend Florence Barger that the army “shovels Egyptians around like dirt”.

The rest of El Adl’s life was spent in Mansourah, where he inherited his father’s house, married, and set up as a middle man in Egypt’s commodity business, first as a cotton broker and then buying and selling beans. The everyday story of his declining health and finances turn out to be also connected to the war. In August or September of 1918 El Adl was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which over the next few years was to make him increasingly financially dependent on Forster as his health declined. In 1919 he was imprisoned for five months on a false charge of selling firearms. His letters to Forster detail his trial under Martial Law, heard by “a Major, two Lieuts.; and a soldier.,” with the Australian soldiers who framed El Adl acting as witnesses. Following his release, in part enabled by money from Forster, he writes about the conditions in the Egyptian prison, including the guards’ extortion of sex and money in exchange for basic necessities. Already a supporter of Egyptian nationalism, which he comments on in his letters to Forster, El Adl was further politicized and embittered by his experiences, turning the words English and cruel into synonyms in his letters. He wishes that Forster was American, because the “English are revengable.”. El Adl’s health and his finances never recovered, and two years later he and his young son were both dead, remembered by friends and family, and in British modernism via Forster’s writings. Mohammed el-Ad was to become one of the principal inspirations for Foster's literary work. Mohammed el-Adl died the year before "A Passage to India" was finished.

After this loss, Forster was driven to keep the memory of the youth alive, and attempted to do so in the form of a book-length letter, preserved at King's College, Cambridge. The letter begins with the quote from A.E. Housman: "Good-night, my lad, for nought's eternal; No league of ours, for sure" and concludes with an acknowledgement that the task of resurrecting their love is impossible.

My published books: