BURIED TOGETHER

Partner Mohammed el Adl,

Mattei Radev, Bob Buckingham

Queer Places:

Rooks Nest House, Weston Rd, Stevenage SG1 3RW, UK

Dryhurst, Dry Hill Park Rd, Tonbridge TN10 3BN, UK

Hackhurst Ln, Dorking RH5 6SF, UK

Tonbridge School, High St, Tonbridge TN9 1JP, UK

12 King's Parade, Cambridge CB2 1SJ, UK

3 Trumpington St, Cambridge CB2, UK

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

19 Monument Green, Weybridge KT13 8QT, UK

6 Melcombe Pl, Marylebone, London NW1, UK

11 Drayton Gardens,

Kensington, London, UK

Raymond Buildings (5 Gray's Inn Square, Holborn, London WC1R 5AH)

27 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AW, UK

6 Hammersmith Terrace, London W6 9TS, UK

Arlington Park Mansions, 9 Sutton Ln N, Chiswick, London W4 4LA, UK

Thistle Holborn, 36-37 Bloomsbury Way, London WC1A 2SD, UK

Palazzo Jennings Riccioli, Corso dei Tintori, 7, 50122 Firenze FI, Italia

11 Salisbury Ave, Coventry CV3 5DA, UK

Canley Garden Cemetery & Crematorium, Cannon Hill Rd, Coventry CV4 7DF, UK

Edward

Morgan Forster

OM

CH (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English novelist,

short story writer, essayist and

librettist. Many of his novels examined class difference and hypocrisy

in early 20th-century British society, notably

A Room with a View (1908),

Howards End (1910), and

A Passage to India (1924), which brought him his greatest success.

He was nominated for the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 16 different years.[1][2]

He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. He appears as the writer Benjamin Dexter in The

Third Man (1950) by Graham Greene.

Edward

Morgan Forster

OM

CH (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English novelist,

short story writer, essayist and

librettist. Many of his novels examined class difference and hypocrisy

in early 20th-century British society, notably

A Room with a View (1908),

Howards End (1910), and

A Passage to India (1924), which brought him his greatest success.

He was nominated for the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 16 different years.[1][2]

He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. He appears as the writer Benjamin Dexter in The

Third Man (1950) by Graham Greene.

Hugh Owen Meredith was at

Kings College in 1897 and is the H.O.M. to whom ‘A Room with a View’ was

dedicated. Forster started writing ‘Maurice’, his candid and at the time

unpublishable story of homosexual love, in 1913. It was finished in

1914. Hugh Meredith was one of the friends he showed the incomplete

manuscript to and it is thought that the character of Clive Durham in

the book may have been based on Meredith. Meredith’s reaction was

apparently disappointing for Forster.

Forster was homosexual, which prompted themes in his works, especially

the novel Maurice. Though conscious of his repressed desires, he

was twenty-seven before he yielded to them physically. In 1906 he fell in

love with Syed Ross Masood, a seventeen-year-old future Oxford student he

tutored in Latin. The Indian had more of a romantic, poetic view of

friendship, confusing Forster with constant avowals of his love.[31]

On 7 October 1912, Forster set sail from Naples for India, where he

made his way to Aligarh to visit Masood, and the two of them went on to

Delhi together. In Chhatarpur he met the Maharaja Vishnwarath Singh

Bahadur, lover of boys and seeker of Truth. (This was to be

J.R. Ackerley’s Maharaja of

Chhokrapur.) Then, in December, he met the twenty-four-year-old Maharaja

of Dewas. In their first conversation, the Maharaja made fun of Forster’s

sexual interests, which Forster thought ill-bred of him. In January 1913,

he rejoined Masood in Bankipore.

by

George Platt Lynes

E. M. Forster 1920

Dora Carrington (1893–1932)

National Portrait Gallery, London

The Memoir Club (Duncan Grant; Leonard Woolf; Vanessa Bell; Clive Bell; David Garnett; Baron Keynes; Lydia Lopokova; Sir Desmond MacCarthy; Mary MacCarthy; Quentin Bell; E. M. Forster)

Vanessa Bell (1879–1961)

National Portrait Gallery, London

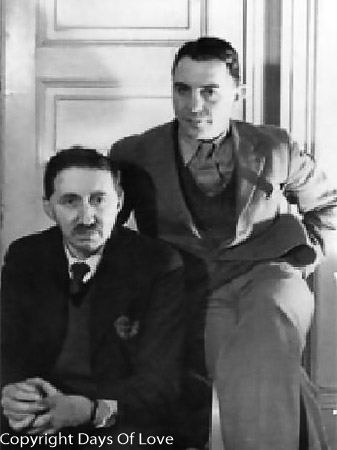

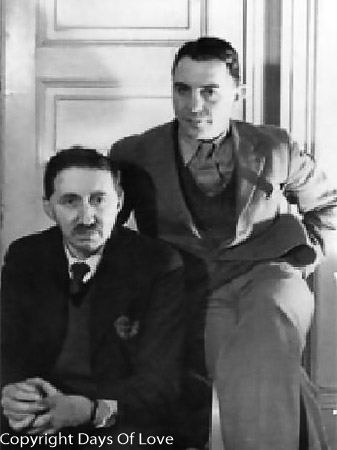

E.M. Forster and Mattei Radev

12 King’s Parade, Cambridge

3 Trumpington St, Cambridge

Forster and his mother stayed at Pensione Simi, now Hotel Jennings Riccioli, Florence, in 1901. Forster took inspiration from this sojourn for the Pension Bertolini in A Room with a View

Forster lived in this house, home of his friends Robert and May

Buckingham, and died here on 7 June 1970. The sign on the wall above the

garage door marks the 100th anniversary of his birth

Canley Garden crematorium

E.M. Forster famously recorded the sight of Cavafy in a street in Alexandria, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe. Forster had been posted to Egypt in October 1915 as a Red Cross searcher, interviewing the wounded for information about the missing. He landed at Port Said on 20 November and took the train to Alexandria, where he booked into the Majestic Hotel. He had come to Egypt for three months but stayed for three years. Through Greek and Grecophile friends, on 7 March 1916, in the Mohammed Ali Club at 2 rue Rosette (now 2 Fouad, Al Attarin Sharq, Al Attarin, Alexandria Governorate), he met Cavafy. It was

Robin Furness – ex of King’s College, now of the Press Censorship Department of the Egyptian Civil Service, translator of the Greek Anthology and of Callimachus – who first took Forster to Cavafy’s flat on the rue Lepsius.

His spirits were then raised by his friendship with a tram conductor,

Mohammed el Adl, aged about seventeen. Forster first spoke to him in

January 1917. Matters developed slowly and it was not until May that they

first met off the tram, in the Municipal Gardens, before going back to

Mohammed’s room. Their first kiss took place at the third of their

off-the-tram meetings, this time in Forster’s room. Obviously proud of

himself, Forster wrote of their romance to friends back in England,

including Edward Carpenter,

Goldsworthy Lowes

Dickinson and Lytton

Strachey. However, in October 1917, Mohammed had to leave Alexandria,

Robin Furness having found him a job with the military on the Suez Canal.

Mohammed got married in October 1918. Forster left Alexandria on 2 January

1919 and was back in England by the end of the month.

In 1921, the Maharaja of Dewas invited Forster to spend six months as

his secretary. On the way back to England in January 1922, he found

Mohammed dying of consumption. He spent a month in Egypt, but seems not to

have called on Cavafy. When he left, Mohammed’s last words to him were,

‘My love to you there is nothing else to say.’ On 17 May he heard that

Mohammed el Adl had died.

In the 1920s, T. E. Lawrence,

who had hardly dared evoke his rape by Turkish soldiers in The Seven

Pillars of Wisdom (‘the citadel of my integrity was irrecoverably lost’),

was delighted by E. M. Forster’s ‘unpublishable’ tales, ‘The Life to Come’

(1922) and ‘Dr Woolacott’ (1927). It was not the skilful reticence that

excited him but the surprising openness: There is a strange cleansing

beauty about the whole piece of writing [‘Dr Woolacott’]. [. . .] I must

confess that it has made me change my point of view. I had not before

believed that such a thing could be so presented – and so credited.

Forster was open to his close friends, but not to the public and a

lifelong bachelor.[13]

He developed a long-term relationship with Bob Buckingham (1904–1975), a

married policeman.[14]

Forster included Buckingham and his wife May in his circle, which included

J. R. Ackerley, a writer and literary editor of

The Listener, the psychologist

W. J. H. Sprott, and for a time, the composer

Benjamin Britten. Other writers with whom Forster associated included

Christopher Isherwood, the poet

Siegfried Sassoon, and the

Belfast-based

novelist

Forrest Reid.

Forster's third novel,

A Room with a View (1908), is his lightest and most optimistic. It

was started as early as 1901, before any of his others; its earliest

versions are entitled "Lucy". The book explores the young Lucy

Honeychurch's trip to Italy with her cousin, and the choice she must make

between the free-thinking George Emerson and the repressed aesthete Cecil

Vyse. George's father Mr Emerson quotes thinkers who influenced Forster,

including

Samuel Butler. The book was adapted as a

film of the same name in 1985 by the

Merchant Ivory team.

Radclyffe Hall wrote The Well

of Loneliness in 1928. As usual, it contained sketches of people she knew:

Noël Coward as Jonathan Brockett,

for instance, and Natalie

Barney as Valérie Seymour. Many prominent readers found the book boring or

ridiculous. T.E. Lawrence said of

it, in a letter to E.M. Forster, ‘I read The

Well of Loneliness: and was just a little bored. Much ado about nothing.’

In 1930, after dining with various homosexual men, including

E.M. Forster and

Lytton Strachey, whose

conversation strayed on to the topic of attractive youths,

Virginia Woolf said she had

received ‘a tinkling, private, giggling impression. As if I had gone into

a men’s urinal.’ Of

Eddy

Sackville-West she said, quite simply, ‘I can’t take Buggerage

seriously.’ Hermione Lee, her biographer, comments, as follows: ‘Like

Simone de Beauvoir twenty years later … the feminist in her deplored the

fact that gay men seemed to want to be women. And she must also have felt

that homosexuality was, for the next generation of writers, an exclusive

exclusive passport for literary success.’

In his essay ‘What I Believe’ (1939), E.M. Forster wrote, ‘if I had to

choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I

should have the guts to betray my country.’

Mattei Radev was a lover of the writer

E.M. Forster, with whom he began an affair in 1960. Radev's friend

Eardley Knollys ran the Storran Gallery in London with his partner Frank Coombs from 1936 and 1944.

Coombs was killed in an air raid in Belfast in 1941, which led to Knollys

closing the gallery in 1944.

Eddy, Lord Sackville-West, who had briefly been Knollys' lover when they were students at Oxford University in the early 1920s, later became a life long friend. In 1945, Knollys, Sackville-West and the music critic

Desmond Shawe-Taylor together bought a Georgian rectory at Long Crichel, Dorset, where they held weekend salons, attended by some of the most notable cultural figures of the period, including

Benjamin Britten,

Nancy Mitford, Graham Greene and

Somerset Maugham. Radev often visited; it was there that he met E.M. Forster. In 1965, Eardley Knollys inherited a large collection of artworks from

Edward Sackville-West, who began the collection in 1938, which he added to and on his death in 1991,

bequeathed to Radev. The collection,

now known as The Radev Collection, consists of more than 800 works of

Impressionist and Modernist art. One of the notable works is Two Male Nudes (1946) by

Keith Vaughan, which was given to E.M. Forster by

Christopher Isherwood. Forster

later gave it to Radev, who he was in love with.

Forster died of a stroke[20]

on 7 June 1970 at the age of 91, at Bob Buckingham' home in Coventry.[16]

His ashes, mingled with those of Buckingham, were later scattered in the rose

garden of Coventry's crematorium, near Warwick University.[21][22]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._M._Forster

- Robb, Graham. Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century

. Pan Macmillan. Edizione del Kindle.

- Rossini, Gill. Same Sex Love 1700-1957: A History and Research

Guide . Pen and Sword. Edizione del Kindle.

- Bourne, Stephen. Fighting Proud . Bloomsbury

Publishing. Edizione del Kindle.

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

- Homosexuals in History, A Study of Ambivalence in Society,

Literature and the Arts, by A.L. Rowse, 1977

Edward

Morgan Forster

OM

CH (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English novelist,

short story writer, essayist and

librettist. Many of his novels examined class difference and hypocrisy

in early 20th-century British society, notably

A Room with a View (1908),

Howards End (1910), and

A Passage to India (1924), which brought him his greatest success.

He was nominated for the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 16 different years.[1][2]

He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. He appears as the writer Benjamin Dexter in The

Third Man (1950) by Graham Greene.

Edward

Morgan Forster

OM

CH (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English novelist,

short story writer, essayist and

librettist. Many of his novels examined class difference and hypocrisy

in early 20th-century British society, notably

A Room with a View (1908),

Howards End (1910), and

A Passage to India (1924), which brought him his greatest success.

He was nominated for the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 16 different years.[1][2]

He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. He appears as the writer Benjamin Dexter in The

Third Man (1950) by Graham Greene.

.JPG)

.JPG)