Queer Places:

The Art Students League of New York, 215 W 57th St, 10019

Algonquin Hotel, 59 W 44th St, 10036

57 W 57th St, New York, NY 10019

Rhinebeck Cemetery

Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, New York, USA

Neysa Moran McMein (January 24, 1888 – May 12, 1949) was an American

illustrator and portrait painter who studied at

The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and

Art Students League of New York.

Alexander Woollcott never

married or had children, although he had some notable female friends,

including

Dorothy Parker and

Neysa McMein, to whom he reportedly proposed the day after she had just

wed her new husband, Jack Baragwanath. Woollcott once told McMein that “I’m

thinking of writing the story of our life together. The title is already

settled.” McMein: “What is it?” Woollcott: “Under Separate Cover.”[4]

Neysa Moran McMein (January 24, 1888 – May 12, 1949) was an American

illustrator and portrait painter who studied at

The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and

Art Students League of New York.

Alexander Woollcott never

married or had children, although he had some notable female friends,

including

Dorothy Parker and

Neysa McMein, to whom he reportedly proposed the day after she had just

wed her new husband, Jack Baragwanath. Woollcott once told McMein that “I’m

thinking of writing the story of our life together. The title is already

settled.” McMein: “What is it?” Woollcott: “Under Separate Cover.”[4]

McMein began her career as an illustrator

and during World War I, she traveled across France entertaining military

troops with

Dorothy Parker and made posters to support the war effort. She was made an

honorary

non-commissioned officer in the

United States Marine Corps for her contributions to the war effort.

McMein was a successful illustrator of magazine covers, advertisements, and

magazine articles for national publications, like

McClure's,

McCall's,

The Saturday Evening Post, and

Collier's.

McMein created the portrait of a fictional housewife "Betty

Crocker" for

General Mills. She was also a successful portrait painter who painted the

portraits of presidents, actors, and writers.

Algonquin Round Table members were entertained at her West 57th Street

studio, where she was known for her active parties.

Life magazine wrote an article about adult party games, which featured

stories about McMein's parties. She had an open marriage to John G.

Baragwanath, during which she had affairs with

Charlie Chaplin and

George Abbott. Baragwanath described their marriage as a successful one

based upon a deep friendship.

Sally James Farnham, Neysa Moran McMein, 1920, sculpture.

McMein and Farnham worked in neighboring studios at 57 West 57th Street. The

bust is dated 1920 and signed Sally James, a shortening of her full

signature, which she used randomly between 1917-1920. The bust is in a private

collection today.

Edna St Vincent Millay by Neysa McMein

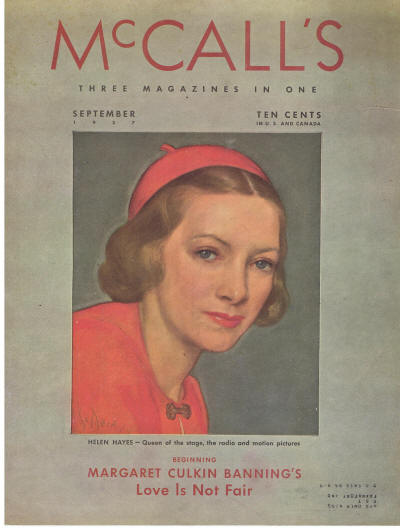

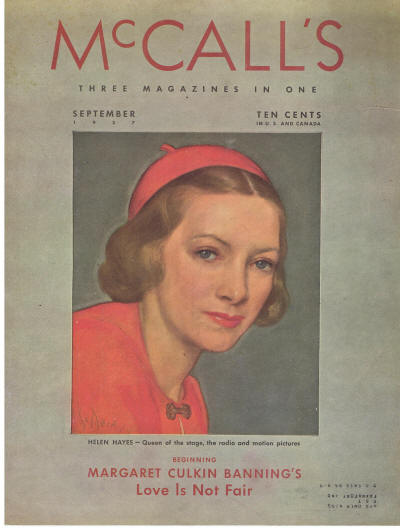

Helen

Hayes by Neysa McMein

Helen

Hayes by Neysa McMein

Dorothy Thompson by Neysa McMein

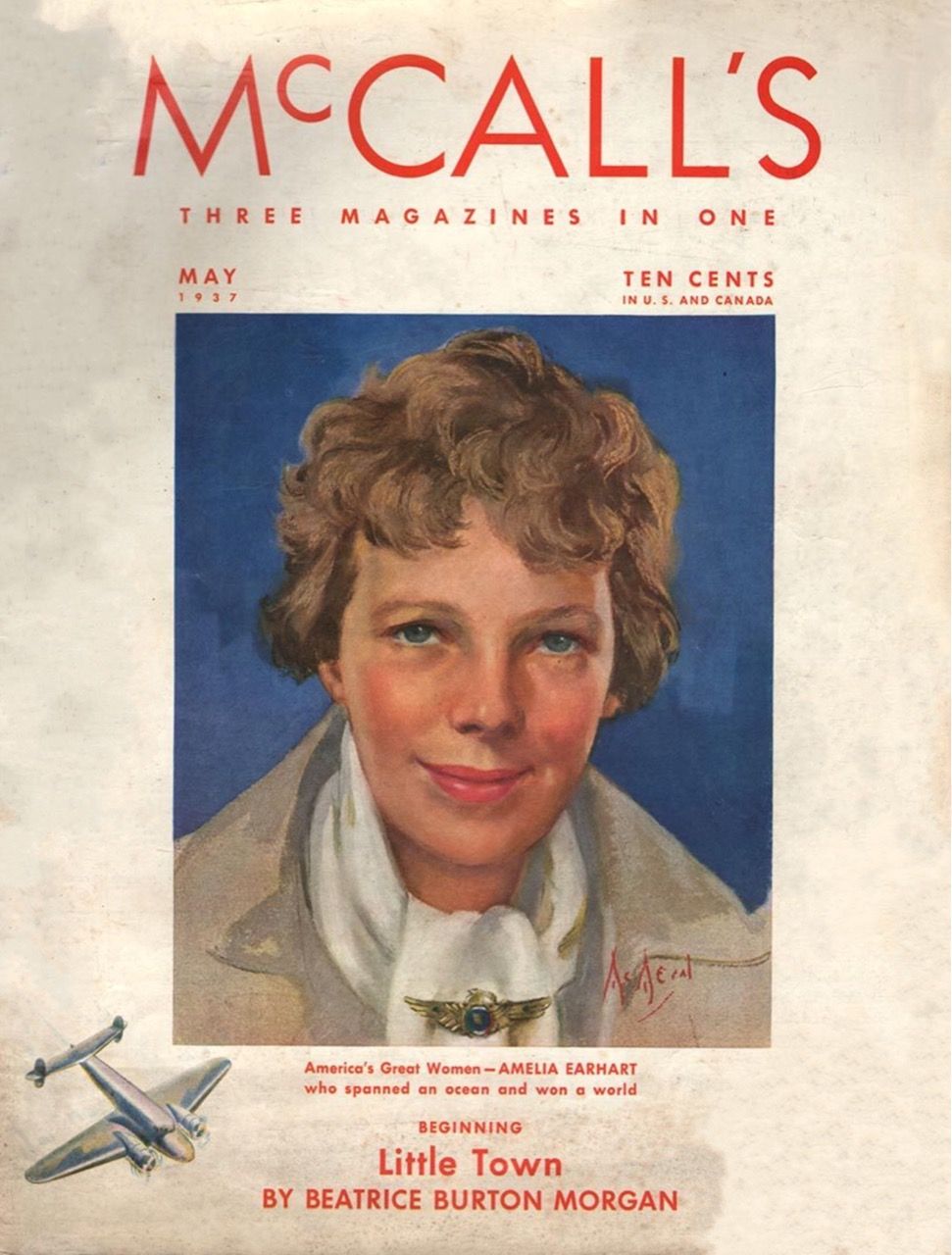

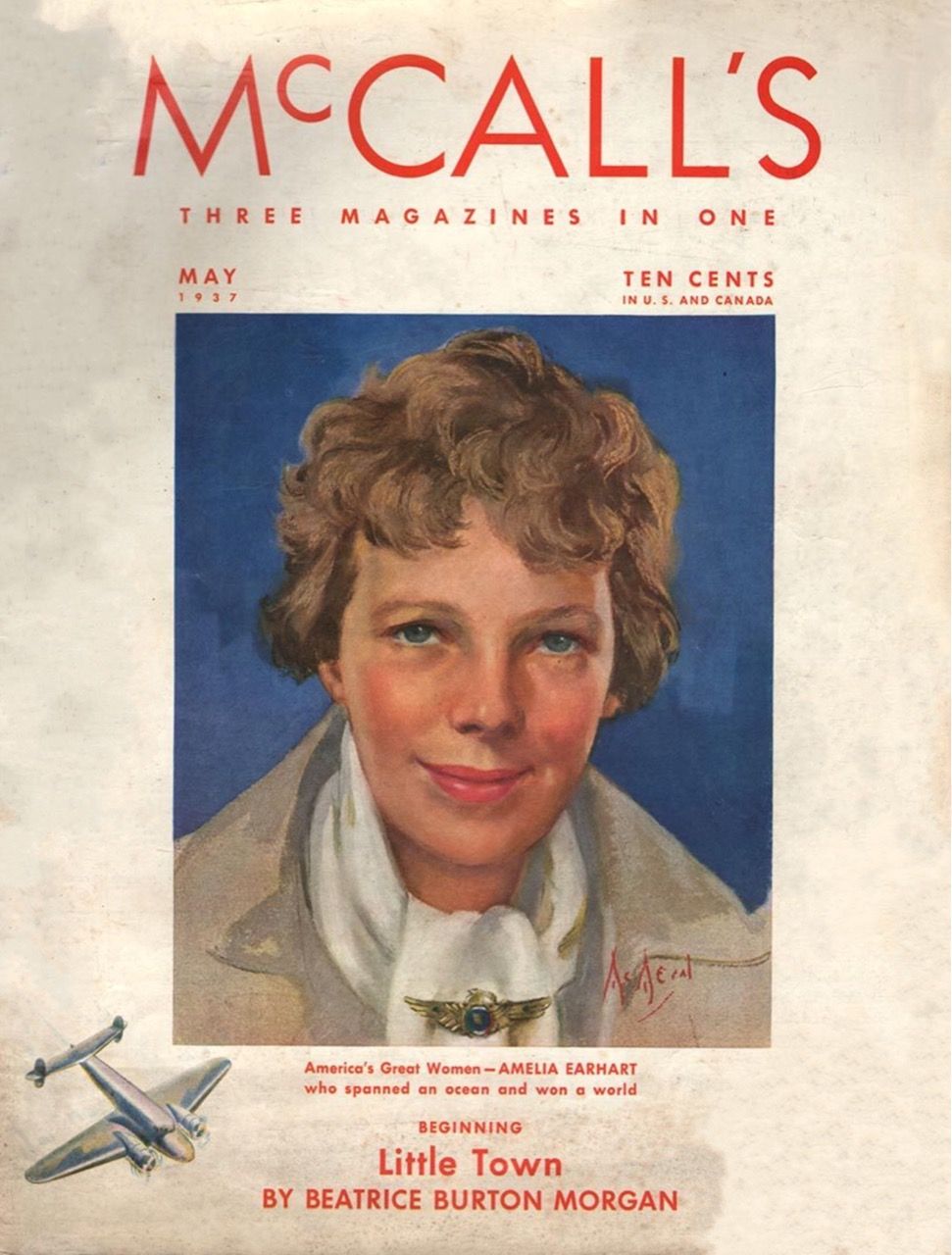

Amelia Earhart by Neysa McMein

Beatrice Lillie by Neysa McMein

Billie Burke by Neysa McMein

Janet Flanner by Neysa McMein

While in New York, Janet Flanner

moved in the circle of the Algonquin Round Table, but was not a member. She

also met the couple, Jane Grant and Harold Ross, through Neysa McMein. It was based on this connection that Harold Ross offered

Flanner the position of French Correspondent to the New Yorker.[1]

She was inducted into the

Society of Illustrators' Hall of Fame in 1984, 35 years after her death.

McMein was one of 20 Society of Illustrators' artists to have their work

published on a United States Postal Service Collectible Stamp sheet in 2001.

Marjorie Frances McMein[a]

was born in

Quincy, Illinois[2]

on January 24, 1888.[3]

She was the daughter of Harry Moran and Isabelle Parker McMein.[4]

Harry McMein was a reporter before he worked for the McMein Publishing

Company, a family business. Due to his alcoholism, his relationship with his

wife was strained.[5]

McMein had musical, acting, and artistic talent. After graduating with

honors in 1907 from the Quincy High School,[4]

she attended

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. McMein worked at a large

millinery firm, where she became lead designer.[4]

In 1911[4]

or 1913, she went to New York City[1][5]

and after a brief stint as an actress

[2] in several of

Paul Armstrong's plays,[6]

she turned to commercial art. On the advice of a

numerologist, she adopted the name Neysa.[2]

John Baragwanath, her husband, stated that she chose the name Neysa after

meeting one of

Homer Davenport's fillies at his stables. Whatever the original impetus

for the change, McMein thought that the name Neysa "had a commercial value"

above that of her birth name.[4]

McMein studied at the

Art Students League of New York[7][1]

in 1914.[5]

McMein sold her first drawing to the

Boston Star in 1914.[5]

She created

Harry Horowitz's portrait in 1915 before he was executed for

Herman Rosenthal's murder.[5]

That year, she sold an illustration for the cover of

The Saturday Evening Post[5]

and her Misinformation illustration appeared on the May 8, 1915, cover

of

Puck magazine.[8]

She became known for her portrayal of "All American Girls."[4]

McMein made posters for French and United States governments during World

War I, as did Thelma Cudlipp, Helen Hyde[7]

and

Mary Brewster Hazelton.[9]

Posters that she made also were used by the

American Red Cross in its fund-raising campaigns.[4]

She traveled across France to entertain the troops in 1918.[4]

Of her time at the

Western Front, McMein said, "Since I have lived through air bombing I

never will be frightened by anything on earth. The terror of air raids cannot

be imagined. They are heralded by the blowing of sirens and the ringing of

church bells, and amid this din the lights are extinguished and then suddenly

come the bombs, falling no one knows where. The noise they made is worse than

that of the battles."[5]

McMein made portraits of some of the soldiers, drew cartoons, and colored

the design of the Indian head insignia that was then used by the

93rd Bomb Squadron to denote the number of German planes that a given

plane shot down by drawing a German black cross over one of the bear teeth in

a necklace worn around the Indian head.[10][b]

She returned to the United States to care for her mother after her father

died.[4]

While in Quincy, she spoke at two fund-raising drives. "[McMein] was the main

attraction. The theater was filled. She was an excellent speaker; very witty

and clever," according to Sarah Carney.[4]

For her efforts supporting the U.S. war effort, McMein was appointed an

honorary

non-commissioned officer in the

United States Marine Corps, one of only three women to be so honored.[11]

Her illustrations appeared on the covers and within articles for

McClure's

magazine by 1919.[13][c]

By the 1920s, McMein and

Jessie Willcox Smith were two of the major women magazine illustrators of

their time. Together, they created hundreds of covers for

McCall's

and

Good Housekeeping magazines.[14]

Joseph Bernt, author of the article "The Girl on the Magazine Cover: The

Origins of Visual Stereotypes in American Mass Media" found that both women

and

Norman Rockwell generally portrayed women in covers and illustrations as

mothers, with scenes centered around children, during the 1920s and 1930s.

Within the covers of the magazine were illustrations made by the three artists

to sell consumer products, like Orange Crush, Ivory soap, Chesterfield

cigarettes, and Holeproof Hosiery.[15]

Following World War I, increased emphasis of family life was presented in mass

media following a period when

woman's suffrage and the

New Woman

were depicted in publications from the late 1800s according to Bernt.[15]

Carolyn Kitch, author of the book The Girl on the Magazine Cover,

finds, however, that McMein created illustrations of confident, modern

New Women

for her magazine covers,[16]

while Jessie Wilcox Smith concentrated more steadily on children.[16]

From 1923 through 1937, McMein created all of McCall's covers.[16]

She also supplied work to

National Geographic,

Woman's Home Companion,[4]

Collier's, and

Photoplay.[3]

McMein earned up to $2,500 (estimated equivalent to $32,777 in 2019)[d]

per cover illustration.[2]

She created advertising graphics for

Cadillac,

Lucky Strike cigarettes and

Palmolive soap.[3][4]

Together with artists

Howard Chandler Christy and

Harrison Fisher, McMein constituted the jury for Motion Picture Classic

magazine's "Fame and Fortune" contest of 1921/1922, which discovered the

It girl Clara Bow.[17]

Other promotional activities including judging Coney Island beauty contests or

opening movie houses.[18]

McMein designed silk textiles in the mid-1920s, three examples of which are in

the collection of the

Metropolitan Museum of Art.[19]

In December 1929, she consulted with

Studebaker's design department, with five other women artists and

decorators.[20]

General Mills commissioned her to create the image of

Betty Crocker, a fictional housewife in 1936. She created an official

portrait of Betty Crocker by combining features of the home economists

employed by the company, which helped reinforce that Crocker was a real

person.[21]

The image of the "ageless" 32-year-old was used in advertising and on

packaging until 1955 when Hilda Taylor painted an updated Betty, who also wore

bright red and white clothing.[22]

Like the Betty Crocker image, "Miss McMein was herself a kind of American

demigoddess: the most courted of commercial artists, hostess in her New York

studio to all of the 'Algonquin

wits'—Benchley,

Parker,

Franklin P. Adams—a wit herself. Sophistication lay rouge-deep upon the

personalities of her cover girls; beneath lay reassuring testimonials to

health and wholesomeness," wrote James Gray, author of Business Without

Boundary: The Story of General Mills.[23]

In April 1938, McCall's Magazine did not renew McMein's contract to

produce illustrations for the magazine. By then, magazines could

cost-effectively publish color photographs using four-color machines.[5]

McMein entered the field of portraiture, at first using pastels to depict

Dorothy Parker,

Edna St. Vincent Millay, and

Helen Hayes.[18]

She painted portraits of presidents

Herbert Hoover and

Warren G. Harding, author

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and actors

Charlie Chaplin and

Beatrice Lillie.[3]

McMein also painted

Katharine Cornell,[24]

Kay Francis,[25]

Janet Flanner,

Dorothy Thompson,

Anatole France,

Charles Evans Hughes and Count

Ferdinand von Zeppelin.[5]

She mentored photographer

Lee Miller.[18]

Her father died in 1918 while McMein was overseas entertaining the troops.

She moved her mother Belle from Quincy, Illinois to live with her in New York.[4]

She was an "ardent supporter" of women's political, sexual, and economic

rights.[5]

By 1920, McMein had walked in suffrage parades, traveled overseas extensively,

and had ridden in Count Zeppelin's dirigible.[6]

She rode across an Arab desert with a woman journalist and friend and was

proposed to by an Arab sheik in Algiers. McMein, who was a talented musician,

had written an opera by that time, too.[6]

In 1921, McMein was among the first to join the

Lucy Stone League, an organization that fought for women to preserve their

birth names after marriage in the manner of

Lucy

Stone.[1][26]

McMein—described as a tall, athletic, grave, and beautiful red-head[e]—became

a regular member of the

Algonquin Round Table set,[28][4]

formed after the end of the war.[5]

Her West 57th Street studio in New York City became an "outpost" to the

Algonquin Hotel,[28][4]

which appealed to the "Bohemian" nature of its members,[2]

which included

Dorothy Parker,

Alexander Woollcott,

Edna

Ferber,

Irving Berlin,

Robert Sherwood,

Franklin Pierce Adams,

Robert Benchley,

Alice Duer Miller,

Harpo

Marx, and

Jascha Heifetz.[28]

She was prone to working in her smock at an easel as her guests enjoyed lively

discussions and piano playing.[5]

Berlin finished composing

What'll I Do at McMein's piano during one of her Round Table parties.[29]

McMein provided the cover illustration of Berlin's biography by Alexander

Woollcott.[29]

Walt

Disney,

Ethel Barrymore,

Cole

Porter,[4]

George Gershwin,

H.G. Wells, and

George Bernard Shaw were friends.[5]

Dorothy Parker moved in with McMein in 1920 before renting an apartment in the

same building.[5]

McMein's mother died in 1923.[4]

The same year, McMein married John G. Baragwanath, a mining engineer and

author,[4]

whom she met at a party given by

Irene Castle. Baragwanth was interested in the striking, fine-featured

woman playing the piano while others danced and sang around her.[5]

McMein and Baragwanath had a daughter Joan[4]

in 1924.[5]

Theirs was an

open marriage, and though the proprieties generally were observed, there

were exceptions. In his memoirs, the lyricist and publicist

Howard Dietz recalled hearing that on one occasion, when Neysa noticed

that her model for the day was impatient to leave, she asked: "Have you got a

heavy date?" Model: "Yes, with a great guy, Jack Baragwanath."[30]

Meanwhile, Neysa was involved for several years with the Broadway director

George Abbott, leading

Alexander Woollcott to say that "we now call Neysa’s place in

Port Washington the 'Abbottoir.'"[31]

She also had affairs with

Robert Benchley,[5]

Charlie Chaplin,[2]

who had a house near her cottage in Port Washington,[18]

and a platonic relationship with

Irving Berlin.[2]

This occurred during a period when "[w]omen are for the first time demanding

to live the forbidden experience directly and draw conclusions on this basis,"

according to

Beatrice Hinkle in an article for The Nation.[5]

McMein lived a varied life in search of fun. She interspersed her life as

an artist with riding on the back of an elephant in a parade, taking a swim on

a whim, and enjoying parties.[18]

She hosted parties with games for adults to entertain artists, writers, actors

and other celebrities. Her guests—like

Bing

Crosby,

Anne

Shirley,

Robert Young, and

Bennett Cerf—engaged in games like a quickfire, multiple team version of

charades called "The Game", that is sometimes attributed to McMein.[32]

The spelling game, where each person on a team wore a sign with one letter and

played against another team so see who could arrange themselves the fastest in

the proper order to spell a word, was played at her parties. McMein and the

games that she employed at her parties were featured in a

Life magazine article in 1946.[32]

McMein also entertained at the house she bought with Baragwanath on the

North Shore of

Long

Island in

Sands Point.[5]

In 1942, she broke her back by falling downstairs during a sleepwalking

episode. McMein was then required to have surgery to graft part of her hip to

her spine.[5]

McMein died of cancer on May 12, 1949,[3][5]

in New York City[1]

and was survived by daughter Joan and her husband John Baragwanath.

In her will, McMein bequeathed monies to purchase works of arts annually by

the

Whitney Museum of American Art. The museum bought 72 purchases from 1956,

none of which were McMein's works. Like other illustrators' works, her

illustrations were not considered fine art.[33]

In 1984, McMein was inducted into the

Society of Illustrators' Hall of Fame.[34]

The United States Post Office released a 20-stamp collection in February

2001 that are based upon works created by 20 Society of Illustrators' artists,

including McMein,

Rockwell Kent,

Al Parker,

Howard

Pyle,

Jessie Smith, and

Joseph Leyendecker.[35][36]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neysa_McMein

Neysa Moran McMein (January 24, 1888 – May 12, 1949) was an American

illustrator and portrait painter who studied at

The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and

Art Students League of New York.

Alexander Woollcott never

married or had children, although he had some notable female friends,

including

Dorothy Parker and

Neysa McMein, to whom he reportedly proposed the day after she had just

wed her new husband, Jack Baragwanath. Woollcott once told McMein that “I’m

thinking of writing the story of our life together. The title is already

settled.” McMein: “What is it?” Woollcott: “Under Separate Cover.”[4]

Neysa Moran McMein (January 24, 1888 – May 12, 1949) was an American

illustrator and portrait painter who studied at

The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and

Art Students League of New York.

Alexander Woollcott never

married or had children, although he had some notable female friends,

including

Dorothy Parker and

Neysa McMein, to whom he reportedly proposed the day after she had just

wed her new husband, Jack Baragwanath. Woollcott once told McMein that “I’m

thinking of writing the story of our life together. The title is already

settled.” McMein: “What is it?” Woollcott: “Under Separate Cover.”[4]

Helen

Hayes by Neysa McMein

Helen

Hayes by Neysa McMein