BURIED TOGETHER

Partner Irene “Renee” Barlow

Queer Places:

Yale University (Ivy League), 38 Hillhouse Ave, New Haven, CT 06520

University of California, Berkeley, California, Stati Uniti

Brandeis University, 415 South St, Waltham, MA 02453, Stati Uniti

General Theological Seminary, 440 W 21st St, New York, NY 10011, Stati Uniti

Hunter College, 695 Park Ave, New York, NY 10065, Stati Uniti

Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, 906 Carroll St, Durham, NC 27701, Stati Uniti

Howard University, 2400 Sixth St NW, Washington, DC 20059, Stati Uniti

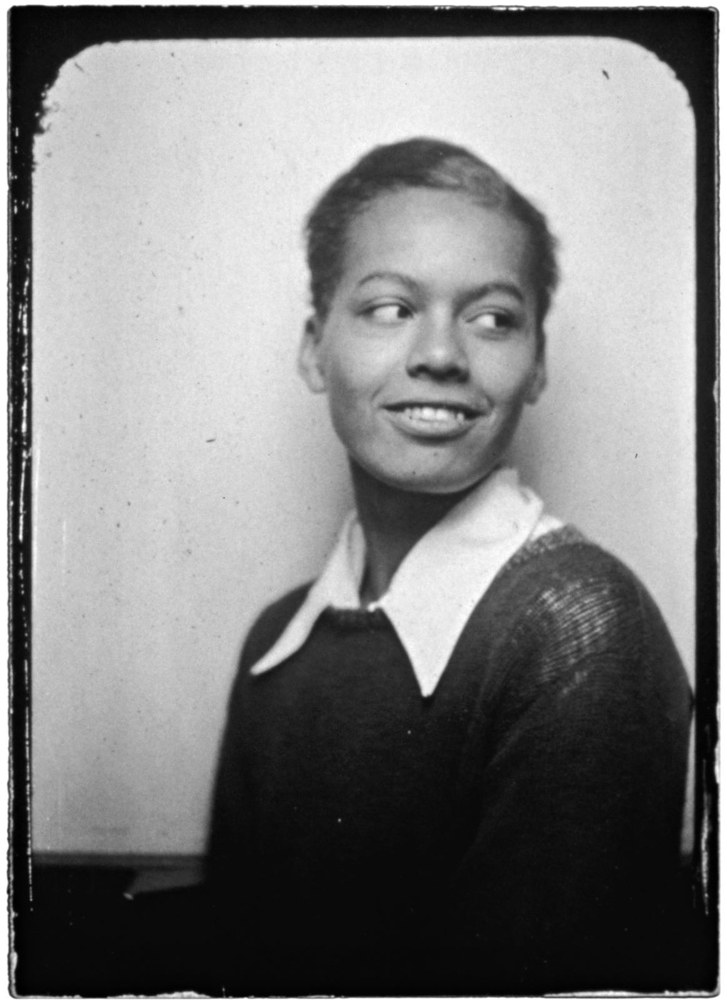

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (1910–1985) was an American civil rights

activist, women's rights activist, lawyer, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn

to the ministry, in 1977 Murray became the first black woman to be ordained as

an Episcopal priest and she was among the first group of women to become

priests in that church.[1][2] Murray was an African American activist. She married briefly in the 1930s, but her most important and lasting relationships were with women. Murray held a variety of jobs; employers included the Works Progress Administration and the Workers' Defense League. In the early 1970s, Murray had a calling to the Episcopal priesthood; in 1976 she received a Master of Divinity degree from General Theological Seminary in New York City. She was the first African American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest; her ordination took place in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on January 8, 1977. Before her retirement in 1984, she served as priest at the Church of the Atonement in Washington, D.C., and at the Church of the Holy Nativity in Baltimore, MD.

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (1910–1985) was an American civil rights

activist, women's rights activist, lawyer, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn

to the ministry, in 1977 Murray became the first black woman to be ordained as

an Episcopal priest and she was among the first group of women to become

priests in that church.[1][2] Murray was an African American activist. She married briefly in the 1930s, but her most important and lasting relationships were with women. Murray held a variety of jobs; employers included the Works Progress Administration and the Workers' Defense League. In the early 1970s, Murray had a calling to the Episcopal priesthood; in 1976 she received a Master of Divinity degree from General Theological Seminary in New York City. She was the first African American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest; her ordination took place in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on January 8, 1977. Before her retirement in 1984, she served as priest at the Church of the Atonement in Washington, D.C., and at the Church of the Holy Nativity in Baltimore, MD.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Murray was raised mostly by her maternal

grandparents in Durham, North Carolina. At the age of 16, she moved to New

York City to attend Hunter College, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

degree in English in 1933. In 1940, Murray sat in the whites-only section of a

Virginia bus with a friend, and they were arrested for violating state

segregation laws. This incident, and her subsequent involvement with the

socialist Workers' Defense League, led her to pursue her career goal of

working as a civil rights lawyer. She enrolled in the law school at Howard

University, where she also became aware of sexism. She called it "Jane Crow",

alluding to the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern

United States. Murray graduated first in her class, but she was denied the

chance to do post-graduate work at Harvard University because of her gender.

She earned a master's degree in law at University of California, Berkeley, and

in 1965 she became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical

Science degree from Yale Law School.

General Theological Seminary, NYC

University of California, Berkeley, CA

Hunter College

As a lawyer, Murray argued for civil rights and women's rights. National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Chief Counsel

Thurgood Marshall called Murray's 1950 book, States' Laws on Race and Color,

the "bible" of the civil rights movement.[1]

Murray served on the 1961–1963 Presidential Commission on the Status of Women,

being appointed by John F. Kennedy.[4]

In 1966 she was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women. Ruth

Bader Ginsburg named Murray a coauthor of a brief on the 1971 case Reed v.

Reed in recognition of her pioneering work on gender discrimination, which

articulated the "failure of the courts to recognize sex discrimination for

what it is and its common features with other types of arbitrary

discrimination."[4]

Murray held faculty or administrative positions at the Ghana School of Law,

Benedict College, and Brandeis University.

In 1973, Murray left academia for activities associated with the Episcopal

Church, becoming an ordained priest in 1977, among the first generation of

women priests. Murray struggled in her adult life with issues related to her

sexual and gender identity, describing herself as having an "inverted sex

instinct". She had a brief, annulled marriage to a man and several deep

relationships with women. In her younger years, she occasionally had passed as

a teenage boy.

In addition to her legal and advocacy work, Murray published two well-reviewed

autobiographies and a volume of poetry.

Murray struggled with her sexual and gender identity through much of her

life. Her marriage as a teenager ended almost immediately with the realization

that "when men try to make love to me, something in me fights".

Although acknowledging the term "homosexual" in describing others, Murray

preferred to describe herself as having an "inverted sex instinct" that caused

her to behave as a man attracted to women would. She wanted a "monogamous

married life", but one in which she was the man.

The majority of her relationships were with women whom she described as

"extremely feminine and heterosexual".

In her younger years, Murray often was devastated by the end of these

relationships, to the extent that she was hospitalized for psychiatric

treatment twice, in 1937 and in 1940.

Murray wore her hair short and preferred pants to skirts; due to her slight

build, there was a time in her life when she was often able to pass as a

teenage boy.

In her twenties, she shortened her name from Pauline to the more androgynous

Pauli.

At the time of her arrest for the bus segregation protest in 1940, she gave

her name as "Oliver" to the arresting officers.[69]

Murray pursued hormone treatments in the 1940s to correct what she saw as a

personal imbalance

and even requested abdominal surgery to test if she had "submerged" male sex

organs.

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (1910–1985) was an American civil rights

activist, women's rights activist, lawyer, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn

to the ministry, in 1977 Murray became the first black woman to be ordained as

an Episcopal priest and she was among the first group of women to become

priests in that church.[1][2] Murray was an African American activist. She married briefly in the 1930s, but her most important and lasting relationships were with women. Murray held a variety of jobs; employers included the Works Progress Administration and the Workers' Defense League. In the early 1970s, Murray had a calling to the Episcopal priesthood; in 1976 she received a Master of Divinity degree from General Theological Seminary in New York City. She was the first African American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest; her ordination took place in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on January 8, 1977. Before her retirement in 1984, she served as priest at the Church of the Atonement in Washington, D.C., and at the Church of the Holy Nativity in Baltimore, MD.

Anna Pauline "Pauli" Murray (1910–1985) was an American civil rights

activist, women's rights activist, lawyer, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn

to the ministry, in 1977 Murray became the first black woman to be ordained as

an Episcopal priest and she was among the first group of women to become

priests in that church.[1][2] Murray was an African American activist. She married briefly in the 1930s, but her most important and lasting relationships were with women. Murray held a variety of jobs; employers included the Works Progress Administration and the Workers' Defense League. In the early 1970s, Murray had a calling to the Episcopal priesthood; in 1976 she received a Master of Divinity degree from General Theological Seminary in New York City. She was the first African American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest; her ordination took place in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on January 8, 1977. Before her retirement in 1984, she served as priest at the Church of the Atonement in Washington, D.C., and at the Church of the Holy Nativity in Baltimore, MD.