Friend Katharine Hepburn

Queer Places:

Cedar Hill Cemetery, 453 Fairfield Ave, Hartford, CT 06114, Stati Uniti

Phyllis

Marian Wilbourn (May 11, 1903 - April 28, 1995) was the live in secretary

(and companion) of Constance

Collier. In the 1950s, after Collier died, Phyllis Wilbourn,

went to live with Katharine Hepburn, and

when she died, she was buried in the Hepburn family plot. Katherine Hepburn

did not make her home with Spencer Tracy but rather within a community of

women.

Laura Barney Harding, Emily

Perkins,

Constance Collier,

Eve March,

Frances Rich,

Phyllis Wilbourn, and finally

Cynthia McFadden were the ones

to provide anchor, solace, and family. Part of Hepburn’s legend has always

been about forbearance: tears are for sissies. Indeed, the people of her inner

circle would always be those who had the steel to grin and bear:

Laura Barney Harding,

Phyllis Wilbourn,

Irene Selznick,

George Cukor.

Phyllis

Marian Wilbourn (May 11, 1903 - April 28, 1995) was the live in secretary

(and companion) of Constance

Collier. In the 1950s, after Collier died, Phyllis Wilbourn,

went to live with Katharine Hepburn, and

when she died, she was buried in the Hepburn family plot. Katherine Hepburn

did not make her home with Spencer Tracy but rather within a community of

women.

Laura Barney Harding, Emily

Perkins,

Constance Collier,

Eve March,

Frances Rich,

Phyllis Wilbourn, and finally

Cynthia McFadden were the ones

to provide anchor, solace, and family. Part of Hepburn’s legend has always

been about forbearance: tears are for sissies. Indeed, the people of her inner

circle would always be those who had the steel to grin and bear:

Laura Barney Harding,

Phyllis Wilbourn,

Irene Selznick,

George Cukor.

With her short brown hair, heavy eyebrows, and precise manner of speech, Phyllis fit the image of the classic spinster. Four years older than Katharine Hepburn, she was born in Rochford, Prittlewell, Essex, in May 1903, the middle of three daughters of Horace and Florence Wilbourn. “Faded gentility,” the family was called by Janet Jordon, whose nanny was Phyllis’s sister Jeannie. Horace Wilbourn may have rolled his sleeves up as a trader on the Baltic Exchange, but his wife’s family had a distinguished pedigree of service to the Crown: Sir George Pocock, an admiral in the Royal Navy, was interred in Westminster Abbey.

By Phyllis’s generation, however, the family had been reduced to moving from town to town—from Westcliff to Teddington to Malden—as Horace struggled to find work. Yet even as they bowed to the reality that their three daughters would need to find jobs, so conscious of their heritage did the family remain that the girls were not allowed, according to Janet Jordon, “to enter a profession which would have required the wearing of a uniform.” While it’s been written that Phyllis received nursing training in England, Jordon said that was not true; a nurse’s uniform was forbidden. Rather, Phyllis was sent to secretarial school.

Of the three daughters of Horace and Florence Wilbourn, “the only one who showed any ‘go’ was Phyllis,” according to her cousin George Andrew Pocock. Her sisters, who also never married, became nannies. Phyllis had other ideas. In 1925, the ambitious twenty-two-year-old somehow came to the attention of Constance Collier, then one of the most popular actresses on the London stage. Soon Phyllis was part of a dazzling, cosmopolitan world. Her cousin George remembered being taken backstage to meet Collier and Ivor Novello. In 1931, Phyllis even played a small part in Peter Ibbetson, which Collier directed on Broadway.

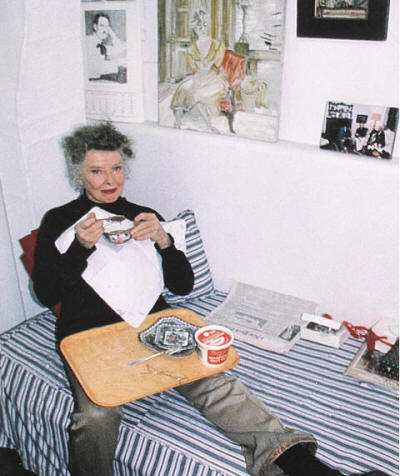

A KATHARINE HEPBURN PAINTING OF HER LONGTIME SECRETARY PHYLLIS WILBOURN WHICH HUNG IN HER HOME

It is a testament to her affection for Phyllis Wilbourn that Katharine Hepburn not only created this beautiful portrait, but kept it in her kitchen, a place where she spent a lot of time and where guests naturally gathered. Wilbourn was, in Hepburn's words, "my right hand" for over forty years. She was known as Hepburn's lady-in-waiting because, as she herself declared when asked what her job was, "I wait." She seems to be doing exactly that in this painting. Hepburn met Wilbourn when she received coaching from actress Constance Collier, for whom Wilbourn had worked. According to Hepburn's goddaughter, Valentina Fratti, "Phyllis was calm and never fazed by the tumult on 49th street, in Fenwick, or anywhere else. She would sit quietly and without knowing it, make the most astute comments in her gentle British accent." Hepburn called her "a selfless person working for a totally selfish person ... an angel."

Since the 1930s, Constance Collier, a diabetic, had been tended to by a devoted companion, an English girl named Phyllis Wilbourn. “In those days, they called them be-withs,” said Noel Taylor. Collier preferred the term secretary, but everyone knew Phyllis did far more than answer telephones. She was there to eat breakfast with Collier, to read the newspapers to her, to clasp her diamond necklace for her on those evenings they went to the theater. In return, Collier gave Phyllis—a rather simple girl from a small town in Essex—access to a sparkling world. “I spent my life with an angel,” Phyllis later told Hedda Hopper. They came as a pair, and everyone respected that. When Katharine Hepburn asked Collier to travel with her to London for The Millionairess, she was dismayed to see that Binkie Beaumont had paid for only two transatlantic passages. Knowing Collier would never leave without her Phyllis, Hepburn exchanged the two first-class tickets for three fares on a less expensive ship. Some friends assumed that, early on, Collier and Wilbourn had been lovers. By the 1950s, however, when Collier was over seventy, their relationship was devoted yet platonic, according to Noel Taylor, who knew both of them. Still, Collier had always been close with some of the theater’s best-known lesbians. She was an early mentor and lifelong intimate of Eva Le Gallienne, and she often socialized with Mercedes de Acosta. Some friends believed Collier first met Hepburn in the early 1930s at a party given by Hope Williams. Such a Sapphic association swirled around Collier that Alfred Hitchcock hired her in 1948 specifically for the lesbian air she’d bring to a small part in Rope—though Arthur Laurents said Hitch later worried that her husky voice might actually be pushing it too far.

In 1951, Hepburn set off on her journey, first to London and then to Europe. She travelled with Constance Collier while Collier’s companion, Phyllis Wilbourn. Hepburn embarked on the America in 1952, with Constance Collier and Phyllis Wilbourn once more at her side. For much of 1953, Irene Selznick would be a boon companion for Hepburn, who had just turned forty-six. When Hepburn wasn’t with Selznick, she was with Collier and Wilbourn, or at dinner parties with Nancy Hamilton or Eve March. In 1954 Hepburn was in Venice with Collier and Wilbourn.

When Collier died in New York in 1955, Katharine Hepburn was unable to return to New York in time for the memorial service; she stopped by on her way to Australia and invited the bereaved Phyllis Wilbourn to accompany her on the tour. Wilbourn was grateful for the offer, but she and Marjorie Steele, wife of the grocery chain heir Huntington Hartford, were taking Constance’s ashes back to England for burial. Hepburn assured her that the tour would be her own tribute to Collier.

When Collier died, Wilbourn’s world had come to a crushing standstill. Her grief was overwhelming. “I have never had any contact with death before,” she wrote to George Cukor, “but now I find myself remembering the oddest little things and the wonderful wisdom and humor.” What brought Wilbourn out of her depression was “a wonderful talk” with Hepburn. “Greta Garbo wanted me to look after her,” Wilbourn later told Scott Berg, “but then Miss Hepburn stepped in and swept me away, thank goodness.”

Exactly when Wilbourn became Hepburn’s steady companion is unclear. She may have joined her for the last part of the Australian tour. By February 1957, during the filming of Desk Set, Louella Parsons reported that Phyllis Wilbourn “now with Katie.” Hepburn said, “Isn’t it from the sublime to the ridiculous? Constance was so social-minded and loved people and had so many visitors, and I live so quietly and see almost no one.”

Becoming a U.S. citizen in 1957, Wilbourn understood her life was now inextricably bound with Hepburn’s. She cooked, cleaned, and typed letters, and for miles and miles of highway she sat beside Hepburn and endured her moods. She was simply there for a woman who could not, ever, abide being alone. “She is a totally selfless person,” Hepburn said in her memoir, “working for a totally selfish person.” Hepburn wasn’t totally selfish—her ministrations to Spencer Tracy prove that—but once she’d made him his dinner and seen him safely tucked into bed, she’d come back home to Wilbourn and expect her own dinner to be waiting for her. And it always was.

Hepburn and Wilbourn were not, as some have presumed, lovers. Though Wilbourn was with Hepburn from sunrise until late at night, she maintained her own apartment on East Seventy-second Street, which, at least for a time, she shared with another woman. When it came to the word lesbian, Wilbourn could be as touchy as Laura Barney Harding. Introducing Wilbourn to Scott Berg, Hepburn called her “my Alice B. Toklas,” prompting great umbrage from Wilbourn, who complained the description made her sound like “an old lesbian.” Hepburn was amused. “You’re not what, dearie, old or a lesbian?”

“Neither,” Wilbourn insisted. Those who remembered her relationship with Collier, however, thought she may have been protesting too much.

My published books: