Queer Places:

5 Rue des Écoles, 75005 Paris

15 Rue de l'Echaudé, 75006 Paris

26 Rue de Condé, 75006 Paris

Cimetière Parisien de Bagneux, 92220 Bagneux

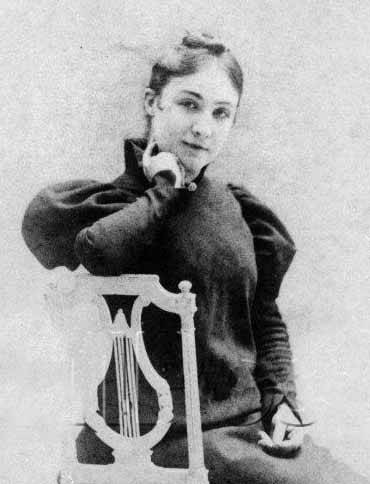

Rachilde was the

pen name

and preferred identity of novelist and playwright Marguerite

Vallette-Eymery (February 11, 1860 – April 4, 1953). In Rachilde’s witty

novel, Monsieur Vénus (1884), published when she was twenty-four, the

amazonian Raoule (‘the Christopher Columbus of modern love’) seduces

Jacques, who has the body of a girl and the soul of a woman.

Rachilde was the

pen name

and preferred identity of novelist and playwright Marguerite

Vallette-Eymery (February 11, 1860 – April 4, 1953). In Rachilde’s witty

novel, Monsieur Vénus (1884), published when she was twenty-four, the

amazonian Raoule (‘the Christopher Columbus of modern love’) seduces

Jacques, who has the body of a girl and the soul of a woman.

Born near Périgueux, Dordogne, Aquitaine, France during the Second French Empire, Rachilde went on to become a symbolist author and the most prominent woman in literature associated with the Decadent Movement of fin de siècle France.

A diverse and challenging author, Rachilde's most famous work includes the darkly erotic novels Monsieur Vénus (1884), La Marquise de Sade (1887), and La Jongleuse (1900). She also wrote a 1928 monograph on gender identity, Pourquoi je ne suis pas féministe ("Why I am not a Feminist"). Her work was noted for being frank, fantastical, and always with a suggestion of autobiography underlying questions of gender, sexuality, and identity.

She said of herself, "I always acted as an individual, not thinking to found a society or to upset the present one."[1]

Rachilde remained socially active for much of her life, appearing around town with young men even into her sixties and seventies. There were naturally rumors of licentious adultery, but she had always preferred the company of gay men and men like Maurice Barrès, for whom there was pleasure in the torture of restraint. In 1935, however, when Rachilde was seventy-five years-old, her husband Alfred Vallette died at his desk. Her truly Bohemian phase had ended with her marriage to Vallette. Her active social presence ended with his death. After more than fifty years, her Tuesday salons came to an end.[15][2]

Although Rachilde was married to a man, her experience was not typical of a woman of her day. She distrusted women and envied the privilege of men.[1] She referred to women as the inferior brothers of men.[16] Rachilde was known to dress in men's clothes, even though doing so was in direct violation of French law.[17] Her reasons are not entirely clear, as there is both boldness and polite reserve in a request she filed for a permit to do so:

Dear Sir, please authorize me to wear men's clothing. Please read the following attestation, I beg you and do not confuse my inquiry with other classless women who seek scandal under the above costume.[18]

She did refer to herself as androgynous, but her definition was functional and pragmatic. There was such a thing as a man of letters, not a woman of letters. Hence, she was both a woman and man. Nor was she shy about that, identifying herself on her cards as, "Rachilde, homme de lettres," a man of letters.[19] Her views on gender were strongly influenced by her distrust of her mother and her envy of the privileged freedom she saw in men like her philandering father.[3][4]

I never trusted women since I was first deceived by the eternal feminine under the maternal mask and I don't trust myself anymore. I always regretted not being a man, not so much because I value the other half of mankind but because, since I was forced by duty or by taste to live like a man, to carry alone the heavy burden of life during my childhood, it would have been preferable to have had at least the privileges if not the appearances.[1]

Apart from her marriage and her often flirtatious friendships, Rachilde did engage in love affairs. She had an early affair with a man named Léo d' Orfer, to whom she dedicated Monsieur Venus.[2] Just prior to writing Monsieur Venus, she had an fruitless passion for Catulle Mendès.[4] Though she would later deny even a slight attraction to women, Rachilde also had a relationship with the enigmatic Gisèle d'Estoc, a bisexual woman of some notoriety at the time. It was an affair that unfolded in playful secrecy and ended with tremendous drama in 1887.[20][3][2]

It is unclear just what her thoughts were about sexual pleasure and sensual attraction. Her friend and admirer Maurice Barrès quotes her as suggesting that God erred in combining love and sensuality, that sensual pleasure is a beast which should be sacrificed: "Dieu aurait dû créer l'amour d'un côté et les sens de l'autre. L'amour véritable ne se devrait composer que d'amitié chaude. Sacrifions les sens, la bête."[13] In her work, while she certainly portrays sexual pleasure, she also portrays sexual desire as something powerful, beyond control, and perhaps frightening.[5][21]

Her own sexuality and gender may have been conflicted, but she was not confused in her support of others. In the public sphere, she wrote articles in defense of homosexual love, albeit sometimes with mixed results.[22][3] She counted among her friends openly lesbian writer Natalie Clifford Barney, who found her an enchanting enigma and a tender friend.[7][16] She was well known at the time for her close friendships with gay men, including such prominent and notorious dandies as Barbey d’Aurevilly, Jean Lorrain, and Oscar Wilde, who brought his lover Lord Alfred Douglas to her salons.[5][23] She is known to have appeared at events with Lorrain while he was wearing female disguise.[14] She offered shelter and support to tormented poet Paul Verlaine.[2][3] She may not have been settled with herself, but she did not let it make her unsettled with those she cared about.

The most important impact that Rachilde had was upon the literary world in which she lived. Monsieur Venus caused great scandal, but in general her works were not widely read by the general public and were almost forgotten. There has been a resurgence of interest in her after the 1977 reissue of Monsieur Venus, but even that is often relegated to literary scholars with an interest in feminist or LGBTQ topics.[30]

My published books: