Ralph

Lorenzo Warner (November 28, 1875 - 1941) was a legend in his own time. His creations in Cooksville

quickly brought attention to himself, to his “House Next Door,” and to the

Village of Cooksville, no doubt much to his surprise.

Ralph

Lorenzo Warner (November 28, 1875 - 1941) was a legend in his own time. His creations in Cooksville

quickly brought attention to himself, to his “House Next Door,” and to the

Village of Cooksville, no doubt much to his surprise. Queer Places:

The House Next Door, 11219 N Webster St, Evansville, WI 53536

Eastern Cemetery

Quincy, Gadsden County, Florida, USA

Ralph

Lorenzo Warner (November 28, 1875 - 1941) was a legend in his own time. His creations in Cooksville

quickly brought attention to himself, to his “House Next Door,” and to the

Village of Cooksville, no doubt much to his surprise.

Ralph

Lorenzo Warner (November 28, 1875 - 1941) was a legend in his own time. His creations in Cooksville

quickly brought attention to himself, to his “House Next Door,” and to the

Village of Cooksville, no doubt much to his surprise.

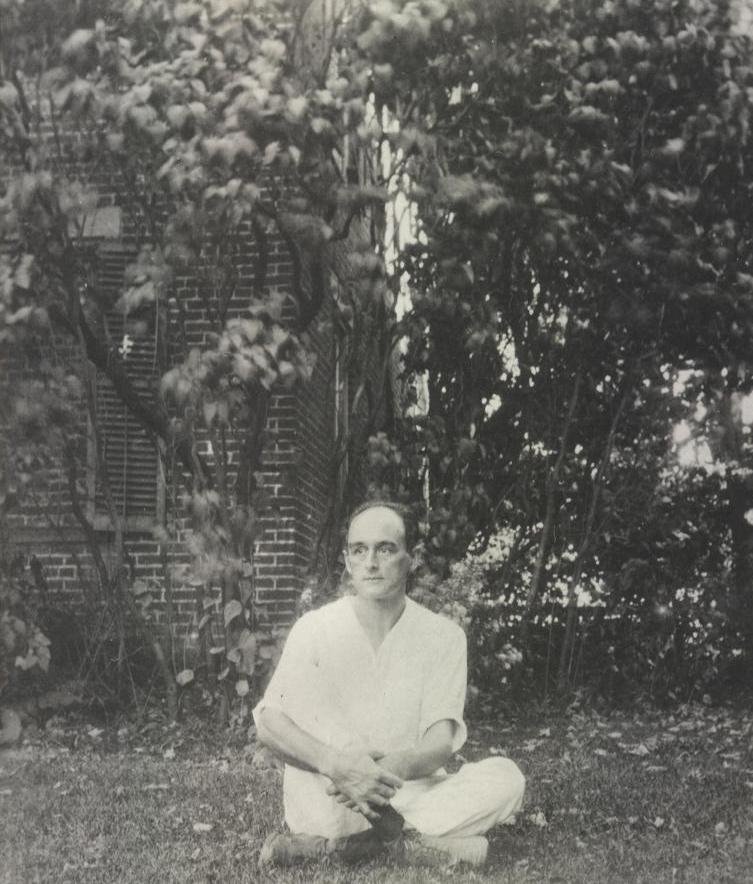

Born in Milwaukee on November 23, 1875, the son of a locomotive engineer, Warner grew up in the fast-growing city. He studied piano, including a stint in Chicago in the late 1890s, and later taught others to play. While living in Racine, Warner made the acquaintance of Susan Porter, a teacher at Racine High. She was a native of Cooksville, Wisconsin, an unincorporated place in the Town of Porter in northern Rock County. Warner arrived in Cooksville in 1911, bought the old Duncan House, and from then on the village was never quite the same.

Milwaukee-born Ralph Lorenzo Warner came to Cooksville from Racine where he lived and where he heard about the quaint village from Susan Porter, a teacher-colleague who had grown up in Cooksville and owned the Backenstoe-Howard House (“Waucoma Lodge”) on Webster Street. Warner bought the “House Next Door” to Susan’s home and immediately set about restoring the old brick Duncan House. He filled it with his growing collections of antiques—furniture, domestic items, art works—many found locally and at the same time he began cultivating his special old-fashioned gardens of herbs, vegetables and flowers.

Warner was undoubtedly the most well-known and influential artist, antiquarian, collector, musician, and gardener that Cooksville—and perhaps, at the time, Wisconsin— ever welcomed, inspired, admired and encouraged. His creativity flourished while residing in the village from 1911 until a stroke caused him to leave in 1933 and live elsewhere, ultimately with his sister in Florida.

His vermilion Cooksville-brick “House Next Door,” built in 1848 was a show case for his extensive collection of antique furnishings and objects from the 18th and 19th centuries, and his quaint residence was surrounded by his old-fashioned gardens. His achievements generated wide-spread interest and praise in the public and in local state and national newspapers and magazines, and the high praise seems to have been especially true when his guests were entertained at his lunches, dinners, teas and occasional over-nights.

The House Next Door

In those 22 years, through his endeavors, Warner’s ability to give present life to the past and to graciously celebrate and share that history was unusual and newsworthy at that time. No doubt some came out of curiosity to see and experience this “antiquarian’s” unusual and single-handed accomplishment. Certainly, Warner’s appreciation—and his sharing— of the “olden days” of early rural Wisconsin village life was unique at the time, a time when the country and the world were changing and entering into the war-torn, industrialized and energetic 20th century.

In a sense, Warner was creating what today might be called an “artistic environment” in which he (and others) could experience, admire and enjoy his re-creations and his interpretation of the past. His home, his gardens, his life were a very personal artistic expression.

He happily shared his accomplishments with neighbors, friends and guests, far and near, and was by all accounts a gracious host and popular member of the community, making cider, entertaining neighbors, and swimming in the Badfish Creek. And he was a gifted pianist and a teacher of piano and arts and crafts, and a talented weaver, a hooker of rag-rugs, and a photographer, producing a number of images of his home, his collections and his gardens. And he traveled extensively and brought back additions to his collections.

“The most remarkable thing about The House Next Door is its owner,” Adelaide Harris wrote in a 1923 House Beautiful article, “It is not easy to catalogue him at all, except to say that he is — in the broader meaning of the term — an artist.”

While some press stories claimed that Warner was a recluse, it seems more likely that Warner was actually a publicity hound, as he was featured repeatedly in the Wisconsin press and national periodicals, including House and Garden in May 1914, House Beautiful in January 1923, the Wisconsin State Journal in 1923, the Wisconsin Magazine in September 1925, the Milwaukee Journal in 1926, Madison journalist Betty Cass’s column Madison Day by Day in the Wisconsin State Journal, and the Ladies’ Home Journal of March 1933.

The diaries he kept during a 1928–1929 trip to Europe show a very sociable man going to the theater and dinner parties and chatting up shopkeepers. The published stories also noted he made multiple trips abroad. During his 1928–1929 trip in London, Warner engaged with two young men. One was Hamilton Beatty of Madison, whom Warner knew was in the English city and eventually discovered at the theater several rows in front of him one night. “Ham,” Warner wrote, “certainly looked good to me and I had the warmest little feeling bout my heart all evening. He did make me feel he was glad to see me.” He subsequently asked the Madisonian to dinner for “a real visit.” On another occasion, he recorded lunch with “Ham.”

Warner was a good friend of Edgar Hellum, who was a teenager growing up in Stoughton when he met Warner in 1923. Hellum appreciated Warner’s preservation efforts, his gardening, his collections and his “antiquarianism.” Ten years later at Warner’s urging, Hellum bought Cooksville’s oldest house, the Cook House (1842), which he remodeled but apparently lived in only infrequently. Shortly thereafter, Hellum went on to Mineral Point to pursue his preservation efforts, no doubt inspired by Warner, and there met his partner Robert Neal with whom he restored several stone houses and served meals, bringing fame to their Pendarvis restorations beginning in the mid-1930s.

In 1940 a notice addressed to Warner’s friends stated: “Ralph Warner revitalized in The House Next Door something important of the early days in Wisconsin and he has done it so faithfully that he has given to the people of today and tomorrow an ‘original document.’ No one could enter that front door without feeling that he was stepping into ‘yesterday,’ a yesterday complete and alive in spirit. Coupled with the material side of the house and its garden was something of a happy philosophy which Ralph Warner gave to all who knew him…”

Warner, a true antiquarian, had found the perfect village and the perfect house in which to immerse himself in his pursuit of his self-fulfillment. He surrounded himself with the best of antique furnishings and decorative objects from the past; he planted his famous gardens with period flowers and shrubs; he expressed himself as an accomplished musician and as a talented artist and immersed himself in his image of the 19th century. In short, in Cooksville he succeeded in creating an outer world that complemented and completed his inner world.

Debilitated by a stroke in 1933, Warner spent his final years with a sister in Florida. Ralph died in Florida in 1941, where he is buried.

My published books: