Partner Edgar Gorby Hellum

Queer Places:

Pendarvis, 114 Shakerag St, Mineral Point, WI 53565

Robert

Neal (July 27, 1906 - July, 1983) was a young man, whom

William Perry Gundry

mentored in interior design. Gundry referred Neal to the English decorator

Syrie Maugham, the estranged wife of author

W. Somerset Maugham, for

employment in her Chicago shop. When Depression-Era economics forced her to

close the Chicago shop, Neal went to work in her New York shop. When that too

had to close, Neal was offered the opportunity to work for her in London, and

he accepted.

Robert

Neal (July 27, 1906 - July, 1983) was a young man, whom

William Perry Gundry

mentored in interior design. Gundry referred Neal to the English decorator

Syrie Maugham, the estranged wife of author

W. Somerset Maugham, for

employment in her Chicago shop. When Depression-Era economics forced her to

close the Chicago shop, Neal went to work in her New York shop. When that too

had to close, Neal was offered the opportunity to work for her in London, and

he accepted.

Neal described meeting the rising star, gay stage designer Oliver Messel: “He is about 28, dark, and is a German Jew. Very wealthy, and very - - - -. After our little visit he extended his hand, which of course I shook. I only hope that I can see more of him, but he flies too high for me. But then.” Presumably, the dashes imply Messel’s homosexuality.

Neal also socialized with young American concert pianist Clifford Herzer from Michigan and gave Gundry reviews of his concerts. Neal described connecting with Emmanuel Braune, a “lad of 22 from Rio de Janeiro.” They went on a several-day Whitsun holiday walking tour of Lambourn and stayed in a private cottage. In another letter, Neal included this interesting tidbit: “I finally mailed a letter of introduction to a Jimmie Watts (an impersonator of women, I understand) that I had given to me in N.Y. before I left.”

During these early days in London, Neal appreciated his association with his employer, Syrie Maugham, who even took him on a quick five-hour visit to Paris. By September 1933, however, he was no longer fascinated with Maugham. Complicating matters was the fact that Neal’s visa renewals required him to state that he was not employed in London. And his duties in the shop were limited when Maugham brought in another partner. Suddenly, Neal’s income was not sufficient to enable him to do the things he wanted to do in London, such as buying handmade English suits from Savile Row.

Neal’s return to America in 1934 after exploring the homosexual world of England shows how another country’s liberating influences could reinforce an individual’s gay identity upon return to the States. Bob Neal’s return to Mineral Point in 1934 would spark his interests in historic preservation, pioneer Cornish culture, and his partner, Edgar Hellum of Stoughton. These were all wrapped up together in a package called Pendarvis. Pendarvis began as an antiques shop and eventually became a restaurant with a Cornish flavor, where the initial meals of full tea were similar to those served at The House Next Door, Cooksville. Neal and Hellum’s restoration of nineteenth-century buildings with pioneer furnishings also followed Ralph Warner’s model.

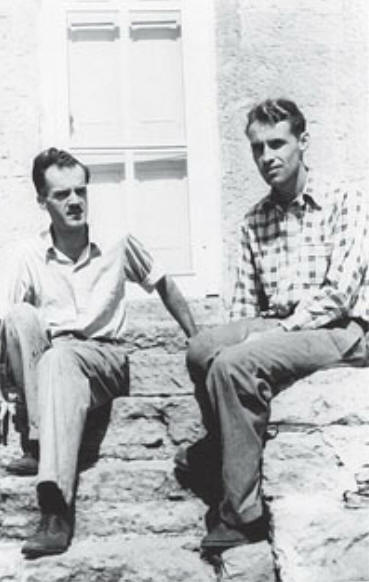

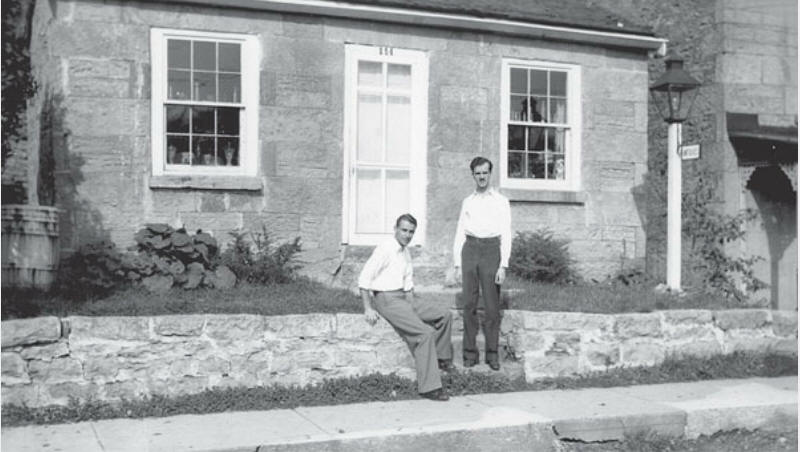

Edgar Hellum (left) and Bob Neal pose in front of the Pendarvis House, one

of several buildings they restored in Mineral Point. MINERAL POINT LIBRARY

ARCHIVES

Most writers who covered Pendarvis during its early period, and even later on, stressed Bob Neal’s time working abroad as a decorator with Syrie Maugham. Sometimes they noted the rooms and sets he and Maugham had worked on in England for Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who performed on the London stage. Neal preserved the autographed celebrity photos the actors presented to him.

William Perry Gundry’s patronage to the local boys extended to his will, in which he left Neal a thousand dollars and Hellum five hundred (which today would represent at least $15,000 and $7,500). When the Gundry estate, Orchard Hill, was threatened with demolition in the late 1930s, Bob Neal was able to devise a strategy to save it by forming the Mineral Point Historical Society and renaming the property Orchard Lawn, thereby getting it off the tax rolls. Later, Bob Neal would serve on the city council, create Wisconsin’s first historic district, and establish the local history room at the Mineral Point library. He lectured frequently on Cornish culture. Hellum, who was of Norwegian descent, would gain fame as a designated Cornish Bard (an old Celtic honor bestowed by a society in the United Kingdom charged with preserving Cornish language and culture). The couple’s success and genuine involvement in their community was undeniable.

After they sold the Pendarvis complex in the 1970s, Neal and Hellum lived separately. Whether this was a result of their growing apart or the need to obscure the nature of their relationship is not known for sure. Later in life, Hellum would recall that Neal’s relatives had treated him “just like I was a member of the family.” That their relationship remained strong and loving even after they sold Pendarvis was made apparent when Neal became sick and Hellum took him in: “We set up a bed and I took care of him for two years.” Hellum remembered telling Neal, “You sure as hell don’t want to go to a nursing home. I said if I have to crawl on my hands and knees [I’ll] look after you as long as I’m able.” When Neal died in 1983, some stories and obituaries noted that his partner survived him; others did not. When Hellum died in 2000, all notices stated that he had been predeceased by his partner.

My published books: