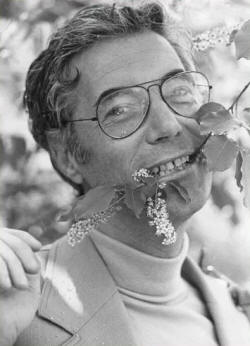

Partner Arthur Marceau

Queer Places:

55 Valley Rd, New Rochelle, NY 10804

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

New York University, 70 Washington Square S, New York, NY 10012

Richard

W. Hall (November 26, 1926 – October 29, 1992), sometimes credited as Richard Walter Hall, was an American novelist, playwright and short story writer.[1]

In the short Country People, a gay writer finds Pride and mystery in a small town. Based on award winning story by writer Richard Hall, Country People is a love letter to LGBT history and literature.

Richard

W. Hall (November 26, 1926 – October 29, 1992), sometimes credited as Richard Walter Hall, was an American novelist, playwright and short story writer.[1]

In the short Country People, a gay writer finds Pride and mystery in a small town. Based on award winning story by writer Richard Hall, Country People is a love letter to LGBT history and literature.

Richard Walter Hirshfeld was born in Manhattan in 1926 to Jewish parents, who later changed the family's name to Hall after experiencing an antisemitic incident.[2] Raised in Westchester County, Hall served in the United States Army during World War II, and was educated at Harvard University and New York University.[3] He worked in advertising and public relations, and taught at Inter American University in San Juan, Puerto Rico in the 1970s.[3]

His first novel, The Butterscotch Prince, was published in 1975.[3] As a book critic and essayist, he contributed to publications including The New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice and The Advocate.[3] He was the first openly gay critic ever admitted to the National Book Critics Circle.[3] His other published books included the short story collections Couplings (1981), Letter from a Great Uncle (1985) and Fidelities (1992), the novel Family Fictions (1991) and Three Plays for a Gay Theater (1983), a compilation of his stage plays Happy Birthday Daddy, Love Match and Prisoner of Love.[3] He died on October 29, 1992, in New York City, of AIDS-related causes.[3] He was predeceased in 1989 by his longtime partner Arthur Marceau (1923–1989).[3]

He posthumously won a Gaylactic Spectrum Award in 2005 for "Country People",[4] a supernatural-themed short story originally from Fidelities which was republished in the 2004 anthology Shadows of the Night and adapted to a short film in 2019.[5][6] Couplings was the subject of an essay by Jonathan Harper in the 2010 non-fiction anthology The Lost Library: Gay Fiction Rediscovered.[7]

Below an essay by Richard Hall, Gay Fiction Comes Home, published in the New York Times in June 19, 1988:

DURING this century, a few lonely voices -not all of them gay males - have created landmark fiction about the homosexual experience. One thinks of Thomas Mann, E. M. Forster, Andre Gide, Jean Genet, Christopher Isherwood, William Burroughs, Gore Vidal, Carson McCullers, James Baldwin. But in the last few decades, these singular voices have blended into a larger chorus. In fact, gay literature has broadened into a general, if controversial, category with clearly definable patterns. To oversimplify the matter, we could say that gay writing has changed since World War II from a literature of guilt and apology to one of political defiance and celebration of sexual difference. But in the last few years it has eased into more private matters, family relations and the search for domestic contentment. Even AIDS hasn't stopped the progression toward self-acceptance and socialization in gay stories and novels. There may be little or no sleeping around (unless the tale is set in a pre-plague era) but there are plenty of characters - friends, relatives, schoolmates, colleagues -who find homosexuality interesting but hardly news, and certainly no reason why a protagonist should duck the basic quest for love, status, power, a mate, career and so forth. (I'm speaking here of fiction about gay males only.) Nowadays, a gay novel rarely explains, complains or apologizes. It assumes that ignorance about homosexuality is a thing of the past and that bigotry signifies either a poor education or a retrograde conscience. Where Zeke Farragut in John Cheever's ''Falconer'' (1977) had to go to jail to discover his love for another man, to learn ''the utter poverty of erotic reasonableness'' (jail presumably being the ideal container for his illegal impulses), the new writers of gay fiction prefer different settings entirely. Quite often their protagonists' difficulties center not on acknowledging sexual tastes but on when to bring a lover home and how to find a spot for the newcomer in the family's affections.

THIS is not to say that pain and unhappiness are absent from gay books, simply that they have become diffused onto a larger area. There is plenty of general unhappiness to which gay men and lesbians may lay claim - Eric Bentley once called it ''the privilege of being no unhappier than other people'' - but it is a universal, shared condition. No more slashed wrists or leaps into the sea. The isolation and ignorance that are the preludes to such crises are harder to come by nowadays, when the flood of information about homosexuality engulfs us all - mostly, and paradoxically, because of AIDS. It is quite possible that the common reader, as Virginia Woolf put it, is ready to allow us ''affection, laughter and argument'' simply because our writers are so engaging and their books so interesting. And because the time has come.

The period of waiting is well dramatized by the appearance in 1984 of the English translation of Marguerite Yourcenar's ''Alexis'' - a mere 55 years after its initial publication in France. ''Alexis'' is the tale of a young aristocrat born in central Europe during the twilight of the Hapsburg empire. It documents his vain struggle to control his erotic urges toward other men. At the end, Alexis stops struggling: ''Life has made me what I am, the prisoner . . . of instincts which I did not choose but to which I resign myself.'' He knows that inner peace will follow self-acceptance.

In reviewing the English translation, I mentioned that Alexis at first suffers from ''self-hatred.'' This provoked a swift response from the author. Writing from Maine, she admonished me that ''Alexis does not feel self-hatred.'' True, he goes through a period of anguish and fear ''in presence of inclinations which his milieu thinks reprehensible,'' and which might lead to social difficulties. But, she concluded, ''Self-hatred is a feeling that does not interest me.''

I was properly chastised. I had been careless, and Yourcenar, publishing this first novel in 1929 when she was 26 years old, was decades ahead of her time. Steeped in my own history, I had missed the clues. Alexis stands as one of the earliest examples of a type now common - the gay man who refuses to perceive his sexuality as a medical or moral problem, who will not internalize the stigmas of his society, and who rejects the shackles of language, whether as silence or evasion, that distort his private truths. Unfortunately, the radical message of ''Alexis'' was very familiar when the translation appeared here and the novel caused little stir.

Yet Alexis' struggles with bourgeois scruples have a wonderfully modern ring. ''Not having known how to live according to a common morality,'' Alexis writes to the wife he is leaving, ''I endeavor at least to be in harmony with my own.'' In the same way, the common morality is generally missing from today's homosexual writing. There will be conflict, a character may slope downward into tragedy, but the causes are not connected to sexual ethics. These have taken a back seat to other despotisms, other dislocations. This is not to say that judgments are-n't being passed in some parts of America, only that fewer writers are paying attention.

Consider ''I Look Divine'' by Christopher Coe, published last year, the story of Nicholas, a beautiful and self-centered young man whom we follow in a narrative told by his older brother after Nicholas's death. There was never a point at which Nicholas worried about being gay. It never occurred to him to question his sexual taste. That came naturally, along with his good looks, his high I.Q. and the adoration of his parents. Nor does he give his sexual choice a name. A name implies other names, opposites, perhaps better and worse. Nicholas has no need for comparisons; he is unique. When a woman at a party asks him what he's going to be when he grows up, Nicholas decides, ''If I have to be something, I think I shall be captivating.'' This he achieves, at some trouble and expense to those who fall under his spell.

IF Nicholas resembles anyone it is Dorian Gray, but without the rotting portrait in the locked room. Nothing Nicholas does - and he does plenty - keeps his soul from shining or turns him into a secret mass of decay. Perhaps the author is commenting on the self-absorbed 80's; if so, his view intersects nicely with Nicholas's narcissism. Being homosexual, living selfishly, imply no evil. There are no psychiatrists to tout the values of the majority. Nor is there a hint of retribution in the fact that the 37-year-old Nicholas is killed by someone unknown. The murder is simply bad luck, a spin at roulette.

All this is far from ''Burning Houses'' by Andrew Harvey (1986), which proves that insouciance like Nicholas's is not a universal of gay fiction. Mr. Harvey writes of an aging homosexual film maker, Adolphe, and his young disciple, Charles, a novelist. Both live in Paris. Adolphe is every inch a queen of the old style, full of self-mockery, self-pity and celebrity gossip. He likes to wear drag and to talk about ''rough trade'' and memories of Maria Callas. Once he came close to suicide. Young Charles, his mirror image, embarks on a hopeless love affair with a married man, which results both in misery and in a novel he reads aloud to Adolphe.

Mr. Harvey is a gifted writer, but this series of turns and arabesques on the gay sensibility in extremis has a tired sound. In style the work looks backward to the jeweled prose of Ronald Firbank, Jean Cocteau, Djuna Barnes and early Thornton Wilder. It also faintly echoes ''Dancer From the Dance'' by Andrew Holleran, the brilliant doomed-queen novel of a decade ago. But instead of genuine humor, poignancy and tragedy, Mr. Harvey gives us cattiness and camp. It is all very arch. Some stereotypes never die; they just go to Paris for a new wardrobe.

The rather prosaic problems facing the young gay couple in last year's ''Surprising Myself'' by Christopher Bram are worlds away from those of either Nicholas or Adolphe. In fact, narcissism is precisely what Joel, the narrator and more volatile of the pair, must overcome in order to make his partnership with Corey endure. The novel contrasts the marriage of the two men with that between Joel's sister Liza and Capt. Bob Kearney of the Army. Although the two gay men have troubles galore, they are not as awful as those facing Liza, who is emotionally bankrupt and has simply ''stopped existing except as Bob's Wife.''

This switch - the successful gay couple and the failing straight one - is refreshing. More striking is the ultimate formation of a new kind of family on a farm in Virginia, a family consisting of Joel's divorced mother, her newly divorced daughter Liza, her baby granddaughter, Joel and his lover. The forces that once had propelled them apart have now been overcome and they can begin to make peace with one another and with their respective pasts. This reinvention of the American family -based on friendship, common interests and choice rather than on sacraments and sex - represents a new social arrangement.

Indeed, finding a family of sorts has become the chief interest of characters in much gay fiction. Protagonists are settling down with relatives, heterosexual women, buddies, lesbians, lovers. Children, the final imprimatur to family life, are being borrowed, adopted, created by artificial insemination. Everyone is trying to get along under one roof. The sexual outlaw, long a staple of gay fiction (the phrase was the title of a book by John Rechy, one of the pioneers in the genre), is giving way to the sexual in-law.

Thus ''Surprising Myself,'' like other new novels, establishes the ordinariness of gay people, their need for relation and intimacy, their commonplace problems of fidelity, power-sharing, home-making. The old need to posit a gay identity and defend it lags behind other, more general human needs. And the tone of this novel reinforces the scaling down of difficulties. Where the old epics, in which the protagonist committed suicide or waged a Rambolike attack on his enemies, used to be shrill or distraught, Mr. Bram writes with an air of puzzled jauntiness. The outside world, his gay characters know, is really more indifferent than hostile.

An interesting variation on the search for domestic bliss is presented by David Leavitt in his richly observed novel, ''The Lost Language of Cranes'' (1986). Both Philip Benjamin and his father, Owen, are gay. But the resemblances in their erotic lives are few. When Philip comes out of the closet in college, he makes up for lost time by approaching near-strangers on campus and saying, ''Hi - I just wanted to let you know, I'm gay!'' Telling his parents requires more time. Philip's main job is to find a lover who, it turns out, does not appear in the book until Philip's childish panics end and he has learned how to be alone. Owen, his father, has problems of a different magnitude - 40 years of hiding his nature, 27 years of marital deceit, more than a decade of furtive sex.

In its history of father and son, the novel sums up the history of gay books themselves. Owen, released finally by his son's frankness, enters the brave new world of the 80's - confessing to his wife, arranging for a second date with a man he likes, making honest contact with his son. He can step out of long years of self-oppression and become a hero in his own story.

The novel - whose third major character is Rose, the wounded wife and mother of these men -may also be viewed as a variation on the new theme of family formation. Owen is his son's erotic heir. He learns, grows, enters new manhood, by using his son as teacher and guide. The young, freed by luck or history, can show the old how to live. ''I'd never imagined you might be gay,'' Owen tells his son at the close, ''I guess because I was so caught up in how I'd tell my straight son the truth about me. Everything you said terrified me, but it also inspired me. . . . That night, I realized, I couldn't go back to the way things were.'' At the same time, Philip can extend his own gay family by including his father in it, reinforcing his homosexuality through blood and kinship. A new, double bond is forged.

No doubt AIDS has rearranged the furniture in much contemporary fiction. But other factors contribute to the renewed interest in family life by gay people. For one thing, readmission to this basic social unit, however modified or reinvented, is a logical corollary to self-acceptance. The lonely pilgrimages to Paris, San Francisco, Capri, Mykonos, Rugen Island, can end. It's easier to go home again, both in life and on the page. Social isolation, self-exile, were sterile solutions after all. Assimilation, or steps toward it, may be possible as America's cultural diversity expands to include different sexual choices.

Another reason for the change in literary venue stems from the passage of time. The gay political movement in America is almost two decades old -long enough for the second and third waves of writers to be heard. Many of the younger ones did not experience the freedoms of the pre-AIDS era. Their world didn't crumble; they simply inherited a new one with AIDS in it. Ghetto life, one-night stands, drugs in the fast lane - all these are receding into the past, along with Saigon and discomania.

The same goes for political action, except where AIDS is involved. The early, tough political battles have been fought and won, or at least advanced to a draw. Now it's time to throw the complex images of gay life onto a different screen, to investigate more complex, less doctrinaire, aspects. The result is a literature more socially nuanced, wider in cast and subject, more appealing to all. It is probably a slight exaggeration to claim that the distance traversed by gay literature in the last 20 years is comparable to the distance between Richard Wright and Toni Morrison or between Sholem Aleichem and Philip Roth, but it is a claim worth making.

NOT that gay men have suddenly been promoted to a new ''maturity'' - a word I've always believed should be applied to bonds and not to people. If it should happen that fast-food sex becomes safe again, then the old thrills and threats, the highs and lows, may well become an obsession of gay fiction. But even then, a primary shift will have taken place - away from secrecy, isolation and taboo. The post-AIDS novel will be quite different from the pre-AIDS model.

Not that the coming-out novel in its pristine liberationist form is dead. Mostly it's just weary. Two recent novels illustrate the problems of breathing new life into an aging form.

With ''The Catholic'' by David Plante (1986), we're back in an anguished world when homosexuals had to wrestle with inauthenticity and alienation, when sex might trigger acute anxiety and genuine love severe religious conflict. Dan Francoeur, the protagonist (aging from 19 to 24), is doubly afflicted - not only gay but a devoted Catholic. In fact, his is ''a personality completely determined'' by religion. The dissection of Dan's remorse, the lawyering of his guilt, occupies - or rather, pre-empts - the book. He is socially quite isolated, trapped in a boring job, with no family in sight. A casual overnight affair provokes an extended crisis. Only at the end does he begin to justify his need for another man when, in an exegetical epiphany, he locates his love among the religious mysteries. The narrow focus of ''The Catholic'' confers a fine intensity and Mr. Plante writes with unsparing honesty. But homosexual guilt and expiation are overfamiliar in fiction. Do we really want a long session with a tortured conscience again? And is a gay affair per se all that interesting?

Perhaps these considerations led Edmund White, in ''The Beautiful Room Is Empty,'' his new novel, to use every stylistic trick in his considerable arsenal. Here is another coming-up-and-out story, taking the narrator into adolescence and young manhood, but the tale is told with wit, humor and aphoristic elegance, and it includes a large cast. Mr. White gives us plenty of surface sunshine to neutralize the familiar and melancholy core of the story, and there are some post-modern literary games along the way. Because of the period covered - from the mid-50's to 1969 - the narrator can be placed midway between David Leavitt's father and son. He faces ignorance, bigotry and self-hatred but at the end there is light. In fact, the narrator turns up at the revolt against police harassment at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village that sparked the modern gay political movement. He imagines a time when ''gays might constitute a community rather than a diagnosis.'' That is just what has happened.

A new work that combines the coming-out novel with the family novel is ''Nebraska,'' a powerful tale by George Whitmore. Here, as in the Leavitt book, there is a blood relative who is homosexual -young Craig McMullen's uncle, Wayne, discharged from the Navy under mysterious circumstances. At one point Uncle Wayne, quite harmlessly, brushes against the boy's genitals. Craig exaggerates the gesture into a monstrous lie of seduction to justify his own attempt to seduce a teen-age friend. In lying he betrays his burgeoning sexuality and his uncle's love. The lie eventually leads to divorce, insanity, even to kidnapping and suicide. It is only after much time and suffering that the adult Craig can locate his uncle in California and make amends.

Mr. Whitmore, who was born in 1945, is writing about the American heartland of an earlier time, but ''Nebraska'' is far from being a tale of singular obsession. It involves three generations of the family. The action flows into all corners of Lincoln, Neb. - courts, stores, factories, churches, bars. Although the novel hinges on sexual self-acceptance, much of it deals with other matters entirely. Young Craig is never yanked out of his social matrix.

If serious gay fiction is signaling a new connection to the larger culture, or at least the hope of it, gay genre fiction never doubted that connection for a moment. The characters in thrillers, mysteries, westerns, even juveniles, interact widely. (Science fiction is a separate case, but in the hands of masters like Samuel R. Delany and others, the matter of same-sex affection on other worlds is getting enthusiastic attention.) Perhaps the characters who move most comfortably through the great world are gay detectives, of whom there are many. One is David Brandstetter, the creation of the prolific Joseph Hansen, who has published nine mysteries in the Brandstetter series, from ''Fadeout'' in 1970 to ''Early Graves'' in 1987. Over the years, Brandstetter, an insurance investigator who happens to be homosexual, has found a lover, learned about himself and grown older, but these events are incidental to his main job. You can't moon about your love life or your identity if you have a corpse on your hands. Indeed, as Mr. Hansen moves his private eye around, he gives us, quite by the way, what other writers work so hard at - a sense of the ordinariness, even the triviality, of gay concerns. This lack of attention to the ''problem'' was delightful when Brandstetter first appeared; it is no less so now.

If our heroes are relaxing, what about minor gay characters? There are as many attitudes as there are authors, and the treatment of small gay roles depends in part on their function in the story. But in some fiction, at least, acceptance of the right of others to be gay marks an important step in the emotional development and erotic freedom of the main characters. By ceasing to condemn, by coming closer, heterosexual protagonists are saying they feel better about all sexuality.

THIS marks a further change in the fortunes of literary homosexuality, since gay characters, over the years, have stood for just about everything undesirable - not only outlaws and aliens but heretics, witches, radicals, criminals, esthetes, Nazis, traitors, spies, you name it. This must be a case of metaphor as illness. Of course, there is always a need for symbols and scapegoats, and the departure of gay people from the list may leave a hole in the demonology of American fiction that will have to be occupied by other minorities less organized and less gentrified.

Not all gay fiction describes worlds in which rifts are closing, breaches ending. There is a large body of work that is still separatist, angry, polemical and highly critical of the middle-class values embedded in the books mentioned here. There is also exciting experimental fiction. And a new literature of the plague, in all its horror, is being born. The number of established authors is expanding too, writers from whom we expect work of predictable style and value - among them Robert Ferro, Andrew Holleran, Armistead Maupin, Ethan Mordden, Felice Picano and others. Still, there is no general agreement about the label ''gay'' as a literary category, either by writers or readers. Many find it confining and prejudicial, a label they would like to escape, believing that it poses the same limitations as do other minority tags. Despite this, some writers are shelving or ignoring ancient fears and moving to a cautious optimism about the future place of homosexuality in American life and letters.

My published books: