Sir

Robert Helpmann CBE (9 April 1909 – 28 September 1986) was an Australian

dancer, actor, theatre director and choreographer.

Sir

Robert Helpmann CBE (9 April 1909 – 28 September 1986) was an Australian

dancer, actor, theatre director and choreographer. Partner Michael Benthall

Queer Places:

3 Trevor Pl, Knightsbridge, London SW7, UK

Sir

Robert Helpmann CBE (9 April 1909 – 28 September 1986) was an Australian

dancer, actor, theatre director and choreographer.

Sir

Robert Helpmann CBE (9 April 1909 – 28 September 1986) was an Australian

dancer, actor, theatre director and choreographer.

He was born Robert Murray Helpman (specifically spelt with one "n") in Mount Gambier, South Australia, and was known as "Bobby" by those close to him. Helpmann was educated at Prince Alfred College, Adelaide, but left school at 14 to focus entirely on ballet. From childhood, Helpmann had a strong desire to be a dancer. This was an unusual ambition in provincial Australia of the 1920s. In a 1974 interview, Helpmann recalled that he was taught the moves and dances of a girl because his dance teacher had no prior experience teaching boys.

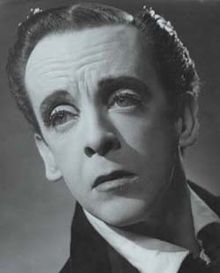

In the Margot Fonteyn biography, Helpmann is described as being dark-haired, pale and having large dark eyes. He had a younger sister Sheila Mary Helpman, and a younger brother Max, or Maxwell Gardiner Helpman, and he welcomed them both into his theatrical world, both of them becoming part of it like audience members and then becoming involved into his style of work as actors themselves.

In 1926 he joined the touring dance company of the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. The introduction came via his father, who was on a business trip to Melbourne, where he met Pavlova who was dancing there. One of the many versions of the cause for his decision to change his surname from Helpman to Helpmann, was that Pavlova, a devotee of numerology, suggested that he should change his surname to avoid his name Robert Helpman having 13 letters.[1]

Robert Murray Helpmann, by Angus McBean, 1946

Following the wartime return of the Sadler's Wells Ballet from the newly occupied Netherlands, Helpmann took a central role in Ninette de Valois' new ballet of 1940, The Prospect Before Us.[2]

TThe highpoint of Helpmann's career as a dancer was the Sadler's Wells Ballet tour of the United States in 1949, with Fonteyn and Helpmann dancing the leading roles in The Sleeping Beauty. The production caused a sensation, which made the names of both the Royal Ballet and its two principals; public and press alike referred to them affectionately as Bobby and Margot. Although Helpmann was past his best as a dancer, the tour opened doors for him in the United States as an actor and director.

In the 1940s, Helpmann turned to production and to acting. He produced his own ballets — Comus (1942), Hamlet (1942), The Birds (1942), Miracle in the Gorbals (1944), Caravan (1946), Adam Zero (1946) and Elektra (1963). He performed roles from Shakespeare at the Canadian Stratford Shakespeare Festival and at the Old Vic theatre company in London, playing the title role in Hamlet two years after having danced the same part.

Helpmann also appeared in many films, including the two Powell and Pressburger ballet films The Red Shoes (1948), for which he was the choreographer, and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951). In 1942 he played the Dutch Quisling in the Powell/Pressburger film One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942) and later played the Chinese Prince Tuan in 55 Days at Peking (1963).

After his return to Australia as co-director of The Australian Ballet, he continued to appear in films. Notable productions included one of his most recognized screen roles, the evil and sinister Child Catcher in the family classic Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). His performance in the film was later rated by Empire magazine as among the 100 most frightening ever filmed. Another family film he starred in was Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1972), in which he portrayed the Mad Hatter. And for The Australian Ballet he co-directed with Rudolf Nureyev the ballet-film Don Quixote (1973), in which he also played the title role. He also starred in the cult 1978 horror film Patrick, in which he broke his back in a scene where he lifted the title character.

In 1965 Helpmann returned to Australia to become co-director of the Australian Ballet, bringing with him an international theatrical reputation and connections with dancers, choreographers and companies across the world. Since he was gay and flamboyant, his arrival in what was at that time a very conservative country caused some consternation. Australians were proud of his international fame, but not sure what to make of him personally. He did not endear himself with the comment: "I don't despair about the cultural scene in Australia because there isn't one here to despair about."

His most significant contribution to the development of dance in Australia was his time with the Australian Ballet, where he created a series of important choreographic works and led the company on a number of international tours. Helpmann joined Dame Peggy van Praagh at the helm of the fledgling company, as her co-director until 1974 and sole director until 1976. He choreographed ballets including Yugen (1965), Elektra (1967, revised from the original version created for the Royal Ballet in 1963), Sun Music (1968), Perisynthyon (1974) and produced and directed The Merry Widow (1975). This was not his first encounter with The Merry Widow – he had directed a production of the operetta in His Majesty's Theatre in London in 1944, with Madge Elliott as "Anna" and Cyril Ritchard as "Danilo". In the 1930s he had also danced in a production with Gladys Moncrieff as "Anna".

The avant-garde nature and sexual overtones of much of his work unsettled many Australians. His most controversial work was The Display (1964), with music by Malcolm Williamson. Helpmann claimed that this was the "first one hundred per cent Australian ballet to have been choreographed", although it was predated by several works and the true first all-Australian ballet was Edouard Borovansky's Terra Australis which premiered in Melbourne on 25 May 1946.[3] The Display used the courtship dance of the lyrebird as a metaphor for Australian male attitudes. Helpmann dedicated the ballet to his friend American actress Katharine Hepburn, who wanted to see a male lyrebird dancing during her visit to Australia in 1955. The novelist Patrick White wrote the scenario, but Helpmann disliked it intensely. It was rejected, causing a furious row between these two extremely opinionated artists. Both the subject matter and the presentation of the ballet were well in advance of Australian tastes at the time.

In 1981 Helpmann worked with the Australian Opera, directing Alcina by Handel, a production later re-staged with Joan Sutherland in the title role. In 1983 he celebrated his sixtieth year in theatre with involvement in productions in the three main auditoriums of the Sydney Opera House: in the Concert Hall he directed Anson Austin and Glenys Fowles in Gounod's Roméo et Juliette for the Australian Opera; in the Opera Theatre he re-choreographed The Display for the Australian Ballet.

IIn the Drama Theatre he starred for the Sydney Theatre Company in the world premiere of Justin Fleming's play The Cobra.. Helpmann's portrayal of the elderly Lord Alfred Douglas, reflecting bitterly on his notorious youthful relationship with Oscar Wilde, was unforgettable. He also played the manservant in the stageplay Stardust,, with Googie Withers and John McCallum.

Helpmann directed the London production of the stage musical Camelot, with designs by John Truscott.

He also did work on a short family cartoon film, Don Quixote of La Mancha,, where he provided the voice of the main character Don Quixote.

According to the novel based upon the life of Dame Margot Fonteyn, Helpmann is characterized as being a very hard man, but also a very kind one. Fonteyn said herself that out of all her partners, Helpmann was her favourite--even more so than her longer and more famous partnership with Rudolph Nureyev. He was also extremely confident and always pushed Fonteyn to her highest potential. The novel also says that Helpmann would stand up to anyone, and that he could look into the face of the devil himself and laugh.

Helpmann retained much of his dancer's agility for years after he had stopped dancing, as shown by a story from Dick Van Dyke about filming Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Whilst filming one of the scenes where the Child Catcher (Helpmann) rides his horse and carriage out of the village, the Cage/Carriage uptilted with Helpmann on board. Van Dyke recalls Helpmann being able to swing out of the carriage and literally skip across the crashing vehicle, and claims that Helpmann did this with incredible grace and agility. Adrian Hall and Heather Ripley, who played Jeremy and Jemimah, described Helpmann as a very generous and kind man. Both would later attend Helpmann's funeral in Australia in the 1980s.

HHelpmann was openly gay. In 1938, Helpmann met a young Oxford undergraduate while fulfilling an invitation to dance at the university. He was immediately drawn to the handsome and intelligent Michael Benthall, and the pair formed a relationship that was to last for 36 years until Benthall's death in 1974. The couple lived and often worked together quite openly for the time. Although devastated by the loss of his longtime companion and collaborator, Helpmann continued to act, direct and produce with his legendary theatrical flair until his death.[1]

Sir Robert Helpmann died in Sydney in 1986, of smoking-related illness. His obituaries in the Australian media were suitably laudatory, but also reserved. The country paid him the highest final recognition it could by honouring him with a state funeral in Sydney,[4] the eulogy calling him "a genius, an outstanding communicator of unique inspiration and insight. He asserted his rights to pursue a path that improved the quality of life of the nation, and defeated the common herd of detractors".[5]

However, an anonymous obituary in The Times of London, likely penned by John Grigg, the former Lord Altrincham, caused upset, particularly one paragraph which stated: "His appearance was strange, haunting and rather frightening. There were, moreover, streaks in his character that made his impact upon a company dangerous as well as stimulating. A homosexual of the proselytising kind, he could turn young men on the borderline his way." It provoked letters of protest, but formed part of a precedent for candid commentary in newspaper obituaries.[6]

My published books: