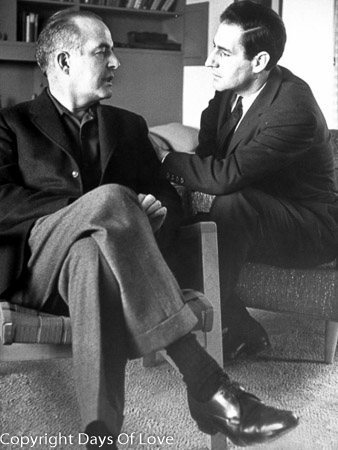

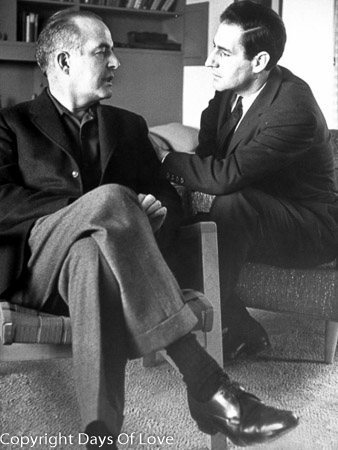

Partner Gian Carlo Menotti

Queer Places:

107 S Church St, West Chester, PA 19382, USA

Curtis Institute of Music, 1726 Locust St, Philadelphia, PA 19103, Stati Uniti

Capricorn, Haines Rd, Bedford, NY, Stati Uniti

Oaklands Cemetery, 120 Market St # 1, West Chester, PA 19382, Stati Uniti

Samuel

Osborne Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer

of orchestral, opera, choral, and piano music. He is one of the most

celebrated composers of the 20th century: music critic Donal Henahan stated

that "Probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such

persistent and such long-lasting acclaim."[1]

Samuel

Osborne Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer

of orchestral, opera, choral, and piano music. He is one of the most

celebrated composers of the 20th century: music critic Donal Henahan stated

that "Probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such

persistent and such long-lasting acclaim."[1]

Addressing the post-WWI period in his enormous overview of

twentieth-century music, but without the ulterior agenda of the anti-gay

conspiracy theorists, Alex Ross writes: Homosexual men, who make up

approximately 3 to 5 percent of the general population, have played a

disproportionately large role in composition of the last hundred years.

Somewhere around half of the major American composers of the twentieth century

seem to have been homosexual or bisexual:

Aaron Copland,

Virgil Thomson,

Leonard Bernstein,

Samuel Barber,

Marc Blitzstein,

John Cage,

Harry Partch,

Henry Cowell,

Lou Harrison,

Gian Carlo Menotti,

David Diamond, and

Ned Rorem, among many others.

Barber's Adagio for Strings (1936) has earned a permanent place in the

concert repertory of orchestras. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music

twice: for his opera Vanessa (1956–57) and for the Concerto for Piano

and Orchestra (1962). Also widely performed is his Knoxville: Summer of

1915 (1947), a setting for soprano and orchestra of a prose text by James

Agee. At the time of his death, nearly all of his compositions had been

recorded.[1]

Barber was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the son of Marguerite McLeod

(née Beatty) and Samuel Le Roy Barber.[2]

He was born into a comfortable, educated, social, and distinguished American

family. His father was a physician; his mother, called Daisy, was a pianist of

English-Scottish-Irish descent whose family had lived in the United States

since the time of the American Revolutionary War.[3]

His aunt, Louise Homer, was a leading contralto at the Metropolitan Opera; his

uncle, Sidney Homer, was a composer of American art songs. Louise Homer is

known to have influenced Barber's interest in voice. Through his aunt, Barber

had access to many great singers and songs.

by Carl Van Vechten

At a very early age, Barber became profoundly interested in music, and it

was apparent that he had great musical talent and ability. He began studying

the piano at the age of 6 and at age 7 composed his first work, Sadness,

a 23-measure solo piano piece in C minor.[1]

At the age of nine he wrote to his mother:

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now

don't cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I

suppose I will have to tell it now without any nonsense. To begin with I

was not meant to be an athlet [sic]. I was meant to be a composer,

and will be I'm sure. I'll ask you one more thing.—Don't ask me to try to

forget this unpleasant thing and go play football.—Please—Sometimes

I've been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad (not very).[4]

Barber attempted to write his first opera, entitled The Rose Tree,

at the age of 10. At the age of 12, he became an organist at a local church.

When he was 14, he entered the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia,

where he studied piano with Isabelle Vengerova, composition with Rosario

Scalero and George Frederick Boyle,[5]

and voice with Emilio de Gogorza.[1]

He began composing seriously in his late teenage years. Around the same time,

he met fellow Curtis schoolmate

Gian Carlo

Menotti, who became his partner in life as well as in their shared

profession. At the Curtis Institute, Barber was a triple prodigy in

composition, voice, and piano. He soon became a favorite of the conservatory's

founder, Mary Louise Curtis Bok. It was through Mrs. Bok that Barber was

introduced to his lifelong publishers, the Schirmer family. At the age of 18,

Barber won the Joseph H. Bearns Prize from Columbia University for his violin

sonata (now lost or destroyed by the composer).[1]

From his early to late twenties, Barber wrote a flurry of successful

compositions, launching him into the spotlight of the classical music world.

His first orchestral work, an overture to The School for Scandal, was

composed in 1931 when he was 21 years old. It premiered successfully two years

later in a performance given by the Philadelphia Orchestra under conductor

Alexander Smallens.[1]

Many of his compositions were commissioned or first performed by such famous

artists as

Vladimir Horowitz, Eleanor Steber, Raya Garbousova, John Browning,

Leontyne Price, Pierre Bernac,

Francis Poulenc,

and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. In 1935, at the age of 25, he was awarded the

American Prix de Rome and was the recipient of a Pulitzer traveling

scholarship which allowed him to study abroad in 1935–1936. He was later

awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1946.[1]

When Barber was 28, his Adagio for Strings was performed by the NBC

Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Arturo Toscanini in 1938, along with

his first Essay for Orchestra. The Adagio had been arranged from the

slow movement of Barber's String Quartet, Op. 11. Toscanini had only rarely

performed music by American composers before (an exception was Howard Hanson's

Second Symphony, which he conducted in 1933).[6]

At the end of the first rehearsal of the piece, Toscanini remarked, "Semplice

e bella" (simple and beautiful).

In 1942, Barber joined the Army Air Corps; there, he was commissioned to

write his Second Symphony, a work he later suppressed. (It was released in a

Vox recording by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew

Schenck.) Composed in 1943, the symphony was originally titled Symphony

Dedicated to the Air Forces and was premiered in early 1944 by Serge

Koussevitsky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Barber revised the symphony in

1947; it was published by G. Schirmer,[7]

and recorded the following year by the New Symphony Orchestra of London

conducted by the composer,[8]

but in 1964 Barber destroyed the score. It was reconstructed from the

instrumental parts.[9]

According to another source, however, it was precisely the parts to the

symphony that Barber had torn up.[10]

Hans Heinsheimer was an eyewitness, and reported that he accompanied Barber to

the publisher's office where they collected all the music from the library and

Barber "tore up all these beautifully and expensively copied materials with

his own hands"[11]

Doubt has been cast on this story, however, on grounds that Heinsheimer, as an

executive at G. Schirmer, would have been unlikely to have allowed Barber into

the Schirmer offices to watch him "rip apart the music that his company had

invested money in publishing".[12]

In 1943, Barber and Menotti purchased a house in Mount Kisco, New York.[13]

Barber won the Pulitzer Prize twice: in 1958 for his first opera

Vanessa, and in 1963 for his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra.

Barber spent many years in isolation after the harsh rejection of his third

opera Antony and Cleopatra. He suffered from depression, and was also

beset by alcoholism.[14]

The opera was written for and premiered at the opening of the new Metropolitan

Opera House on September 16, 1966. After this setback, Barber continued to

write music until he was almost 70 years old. The Third Essay for

orchestra (1978) was his last major work.

Barber died of cancer in 1981 in New York City at the age of 70. He was

buried in Oaklands Cemetery in his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania.[15]

Samuel Barber (1910-1987),

Horatio Alger (1832-1899),

Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876)

and Bill Sherwood (1952-1990),

all descend

from the same Pilgrims, Degory Priest (arrived with the Mayflower), Isaac

Allerton and his wife Mary Morris (arrived with the Mayflower), and Robert

Cushman.

Tony

Scupham-Bilton - Mayflower 400 Queer Bloodlines

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Samuel

Osborne Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer

of orchestral, opera, choral, and piano music. He is one of the most

celebrated composers of the 20th century: music critic Donal Henahan stated

that "Probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such

persistent and such long-lasting acclaim."[1]

Samuel

Osborne Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer

of orchestral, opera, choral, and piano music. He is one of the most

celebrated composers of the 20th century: music critic Donal Henahan stated

that "Probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such

persistent and such long-lasting acclaim."[1]