Queer Places:

1442 Williamson St, Madison Dane, Wisconsin

Forest Hill Cemetery

Madison, Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

Theodore

"Ted" Pierce (March 18, 1907 - January 2, 1999) was a member of a middle class African-American family in Madison, Wisconsin and an associate of several Wisconsin governors. He was very interested in art, especially dance, and was a significant figure in the local homosexual communities.

Theodore

"Ted" Pierce (March 18, 1907 - January 2, 1999) was a member of a middle class African-American family in Madison, Wisconsin and an associate of several Wisconsin governors. He was very interested in art, especially dance, and was a significant figure in the local homosexual communities.

Pierce was born in Chicago on March 18, 1907 to Omar Adams and Ida Pierce Adams Caire. In 1910, he went to live in Madison, Wisconsin with his mother's brother and his wife, Samuel S. and Mollie Pierce, who raised him as their own son. Samuel Pierce was a Pullman porter and an executive messenger to several Wisconsin governors.

The Pierce family on his father’s side came from Louisiana, where his

grandfather had been a member of the Reconstruction state legislature and a

New Orleans judge. Ted Pierce would later claim that the family tradition of

“graceful living” came from the New Orleans branch of the family, whom he

called “suave and polished people.” Also part of the family group was Theodore Pierce's grandmother, Hettie Pierce, who died in 1945 at the age of 115.

She was born into slavery in Rochester, North Carolina, in 1829. Her husband,

John, had been born into slavery in Virginia. Both had been moved into the

Cotton Kingdom lands of Louisiana; when the Civil War ended in 1865, they were

living and working on a plantation. Pierce had several sisters and brothers, including Edwina, Harold, Edgar, and Alyce who lived with their mother in New Orleans.

In her later years, Hettie was often featured in the local press because of

her age and her experiences under slavery. Wisconsin Republican governor

Walter Kohler Sr. and his wife, Charlotte, visited Hettie Pierce with flowers

on her 102nd birthday.

Samuel Pierce had been a Pullman porter, a high-status job for African

Americans, working the Northwestern Railroad’s line between Milwaukee and

Madison. The Pierce family also ran the Sam Pierce Loraine Tailor Shop in the

Hotel Loraine, the most prestigious hostelry in Madison. Sam was an advocate

in 1928 for “a Negro community house” to help new members of the African

American community, since they had no public place for youth activities. When

Samuel Pierce died in 1936, Governor Philip La Follette ordered capitol flags

to fly at half-staff as a token of the community’s esteem of the deceased.

Pierce’s portrait was painted and presented to the State Historical Society in

1958.

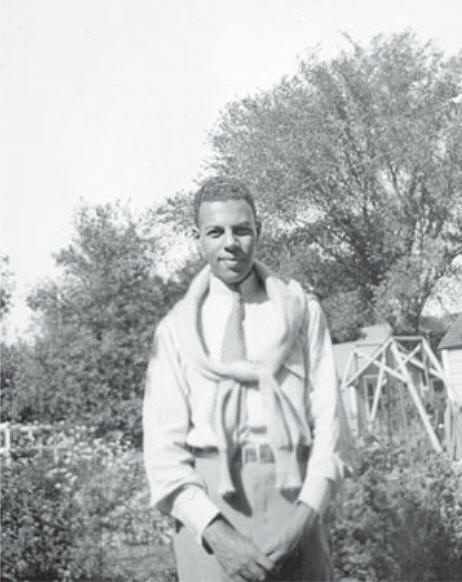

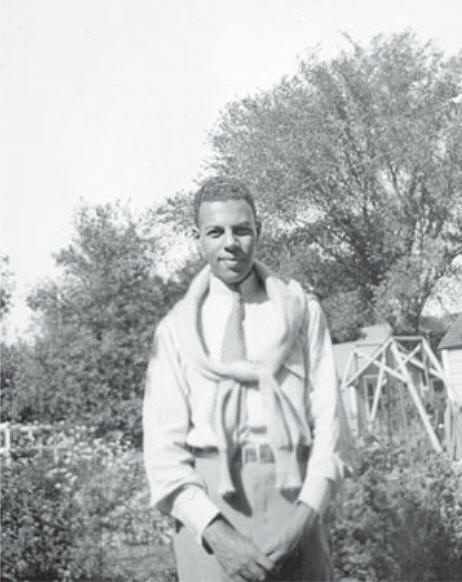

As a student in Madison, a young Ted Pierce attended East High School and

the UW. WHI IMAGE ID 71483

Ted Pierce poses in a living room near a window. He is wearing a tuxedo, with no jacket. PH Mss 934.26.

Professional portrait of Dudley Williams, who was a dancer with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Mr. Williams was a friend of Theodore Pierce.

From 1913 to 1924, Pierce attended Marquette Elementary, Emerson Junior High, Central High schools, and he graduated from East High School in 1924.

The East High School yearbook of 1924 dubbed Pierce “Our Fashion Plate.” His

high school activities included chorus, the technical club, and the Latin

club. A photo of black high schoolers of the era including Pierce remains in

his papers and bears the note “The Elite Club.”

Pierce attended the University of Wisconsin in 1924 and 1925, but did not graduate. Between 1926 and 1936 Pierce managed the tailor shop owned by Samuel Pierce in the Loraine Hotel. Following the elder Pierce's death in 1936, Theodore was appointed to fill his uncle's position of executive messenger by Governor Philip La Follette. He held this job for 11 years under four Wisconsin governors until Governor Oscar Rennebohm eliminated the position in 1947.

Pierce recalled that during the period between the wars, the bellhops at the

Loraine were part of Madison’s gay sexual underground. Single male

travelers—often salesmen, lobbyists, and others who came to do business at the

Capitol—were likely targets for seduction. Perhaps the frequent presence of

single men in Madison was why the Pegasus Bar of the Belmont Hotel on the

other side of Capitol Square was also a gay hangout, a place recalled by

Pierce as “a dream of beauty” on weekends.

Pierce’s boyfriend during the war, originally from St. Louis, worked at the

military base at Truax Field. Within the military, there was a concern about

the possible blackmail of gay folks as security risks regarding sensitive war

equipment.

While working in the governor’s office, Pierce observed how networks

functioned. As the governor’s aide, he met the iconic American actress

Tallulah Bankhead when she came to the

governor’s mansion during Philip La Follette’s tenure. Pierce observed that

Bankhead and La Follette had known each other growing up in Washington, DC,

because their respective fathers had been senators.

Among the gay men in Pierce’s network was actor

Don Pryse Jones, a native of

Portage who sometimes stayed at the American Students’ and Artists’ Center in

Paris. Jones once chattily wrote, “I will go by the Ecole Militaire and watch

the handsome officers, and find a lovely one and send him in this letter to

you.” Pierce truly admired the physical form. He was a major fan of ballet and

recalled bringing “the eternally young, truly beautiful people the performers

of the Dance from the various Ballet companies” to his gay house parties.

One dance enthusiast whom Pierce met was

David Zellmer. While a student at

the UW in the late 1930s, Zellmer performed in campus productions of the

Haresfoot Club, the school’s all-male, cross-dressing theatrical troupe, and

also wrote a column on dance for the Daily Cardinal. After graduating, Zellmer

headed east and joined Martha Graham’s dance troupe, where he also met a

fellow gay dancer, Merce Cunningham.

An occasional letter from Cunningham, the future dance icon, to Pierce

mentions Zellmer. Zellmer’s own correspondence with Pierce after he left

campus continued into the mid-1940s. After World War II, during which Zellmer

served as an officer aviator, he returned to the dance world of New York and

married. In an early letter to Pierce, apparently written when Zellmer was

first in New York with Graham, Zellmer tartly referenced his competition with

Cunningham in those days. “Admit you never really dreamed I could be

interested in glorifying Merce,” he challenged Pierce. In the same letter,

Zellmer deprecated the “chi-chi world” of an artist Pierce had written about

and disparaged gay photographer

George Platt Lynes. In late 1945, Pierce wrote to Zellmer about the

public’s tolerance and acceptance of gay men in dance. Zellmer was annoyed by

the communication. While admitting in his response that “one’s homosexuality

or bisexuality is an integral part of one’s personality,” Zellmer wrote, “I

especially resent the presence of the half-men in dance. They alone have

impeded the progress of male dancing in America by several decades; and

Ted Shawn, to name but one, is a monument to

the decadence and singular lack of taste brought into the theatre by them.

Broadway today still reeks of their influence and presence.”

Before arriving in Madison in the 1950s, world-famous travel writer

Herb Kubly, a New Glarus native, sent

a postcard to Pierce picturing the Chalet of the Golden Fleece and asked to be

“put up at the Pierce Youth Hostel if reservations are still available.”

Lee Hoiby wrote a letter to Pierce

in the early 1950s describing sex in the Milwaukee parks—specifically, meeting

someone at the Solomon Juneau statue. Hoiby, a classical pianist and, later,

composer, hailed from Stoughton; he played at UW’s Memorial Union on Sunday

afternoons and was part of the gay circles in the capital city.

Once Pierce connected with his east side neighbor

Keith McCutcheon, they

discussed their many mutual acquaintances.

Pierce’s interest in young men brought him letters of solicitation for

photos of the male physique in the mid-1950s. Several decades later,

Olin Wood, a UW instructor in French,

sent Pierce and other Madisonians photos of Richard Thomas, John-Boy from

television’s The Waltons, on the beach wearing only a posing strap.

Pierce’s gaydar seems to have been well tuned. He collected fan items of

handsome stars long before they came out. Some of the oldest go back to 1943,

when he collected extensive clippings about

David Gaspar Bacon, an actor who

was stabbed to death at age twenty-nine. Bacon had supposedly gone to swim at

Venice Beach, but police reported that he had picked up a man in his sports

car. One of Pierce’s photos showed Bacon, who was married, wearing women’s

clothes and painting his nails for a 1936 Harvard theatrical. Among Pierce’s

scrapbook items were early notices of the “bachelor” actors

Richard Chamberlain,

Rock Hudson, and

Tab Hunter, collected long before these men came out.

Pierce had created a whole set of loose-leaf binders of scrapbooks, now

lost, of attractive young men; there were clippings from the press and photos

of his circle of gay friends. The black actor

Canada Lee, who had gone from

racetrack roustabout to prizefighter to Harlem jazz bandleader before his

acting career took off, got to know Ted Pierce and would stay in his house

when he came to Madison. Lee played such roles as Caliban in Shakespeare’s The

Tempest. In January 1942 Lee was onstage at Madison’s Parkway Theater

performing in Orson Welles’s Mercury Theater production of Richard Wright’s

Native Son, a role he had performed on Broadway. On one occasion in 1945, Lee

stayed with Pierce when he was in town to be honored by the Madison chapter of

the NAACP. On that trip Lee stated, “I will not play the stock Negro character

since I feel it is a libel on the race.” On Lee’s death in 1952, Madison

newspapers mentioned that he had been a guest of Pierce.

Perhaps the longest-running gay correspondence in the Ted Pierce papers is

the one between Pierce and Willard

Motley, the African American writer who graduated from Englewood High

School on Chicago’s South Side, where he played football. Motley came to

Madison hoping to go to the university. However, his dream could not be

realized because his funds were too low, and at 135 pounds he did not make the

football team. Yet he did meet Ted Pierce. Over the years, Motley would visit

Pierce in Madison and often went to UW football games on those weekends.

In 1956 Pierce was hired by the Acquisitions Department of Memorial Library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and he continued in that position until his retirement in 1972. Suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, he moved to St. Mary's Care Center in August 1998 and died on January 2, 1999.

Ted Pierce, named for Republican president Teddy Roosevelt, who was in

office at the time of his birth, lived on Williamson Street in the family home

until illness forced him into a care center in 1998.

My published books:padding:0px; margin:0px; border:0px;" href="https://www.blurb.com/user/store/elisarolle?utm_source=badge&utm_medium=banner&utm_content=125x125_published">

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Theodore

"Ted" Pierce (March 18, 1907 - January 2, 1999) was a member of a middle class African-American family in Madison, Wisconsin and an associate of several Wisconsin governors. He was very interested in art, especially dance, and was a significant figure in the local homosexual communities.

Theodore

"Ted" Pierce (March 18, 1907 - January 2, 1999) was a member of a middle class African-American family in Madison, Wisconsin and an associate of several Wisconsin governors. He was very interested in art, especially dance, and was a significant figure in the local homosexual communities.