Partner Joe Koberstein

Queer Places:

739 Jenifer St, Madison, WI 53703

Roselawn Memorial Park

Monona, Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

Keith McCutcheon (1904 - August 4, 1968)

was an interior designer.

Keith McCutcheon (1904 - August 4, 1968)

was an interior designer.

He was born in Arena, a Wisconsin River Valley town, in the early twentieth century. He was roughly the same age as Bob Neal and Edgar Hellum. McCutcheon wrote a historical pageant based on Old Helena, a now-lost river town. Viewing himself as a writer, he believed that with the pageant, a WPA project, he had taken a “definite step away from an old and overworked form.”

McCutcheon’s River Valley connections had been evidenced earlier, however, for he spent the year 1930 working with Frank Lloyd Wright as a secretary at Taliesin. Wright’s Hillside School would inspire McCutcheon to write poems, and one poem about Taliesin later appeared in McCutcheon’s first book of published verse. McCutcheon moved permanently from his home community and spent most of his life in Madison. McCutcheon began his explorations of sexual identity while attending the University of Wisconsin in Madison. During his lifetime, as the Alumni Magazine later put it, he was a “poet, artist, and interior decorator.” On campus, he lived in a fraternity through 1927, his senior year. The most revealing expression of McCutcheon’s early struggles with sexual identity appears in Twilight Verses, a sixty-eight-page compendium dated 1932. The cover, drawn by McCutcheon, displayed an image of a man named Leon, the subject of the book’s last sequence of poems. “Sonnets to Leon” describes McCutcheon’s infatuation with another tuberculosis patient at Statesan, the State Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Wales, Waukesha County.

In 1931, McCutcheon published Lyrics of the Night, a forty-page book of poems that is quite different from the earlier handmade version. In August 1933, McCutcheon began contributing a column in the weekly Rio Journal, published as In the Heart of Columbia County, pausing only when he contracted tuberculosis and entered Statesan (later the Ethan Allen School for Boys at Wales, a juvenile detention center). Rio, which is located just southeast of Portage, was a village of 641 in 1930. In the columns, McCutcheon reviewed works by Thornton Wilder, discussed W. Somerset Maugham’s short stories, and recommended Thomas Mann. He praised Oscar Wilde as one of the great literary geniuses of the world and said, “We must not judge his folly.” Writing about Wilde’s De Profundis, McCutcheon said, “Love is a sacrament that should be taken kneeling.”

In May 1934, McCutcheon published “A Group of Love Songs” in The Beacon, which was known as “Wisconsin’s Sanatorium Journal.” The editor thought McCutcheon’s sketches, or articles, approached those of “Vanity Fair and other national magazines in quality.” McCutcheon then published two small books of poetry, each containing seven poems, one of which was written while at Statesan. In 1935 came Seven Sonnets Sung Softly for the Soul and in 1936 Seven Love Poems from Old Nippon. Also during the 1930s, McCutcheon published poems and stories in several issues of the Daily Cardinal, the UW student newspaper. Betty Cass wrote in the Wisconsin State Journal in 1935 that McCutcheon’s “verse was like delicate cameos cut from virgin stone.” Cass knew McCutcheon well enough, as “poet, musician and lover of truly beautiful things of life,” to turn over one of her daily columns to him.

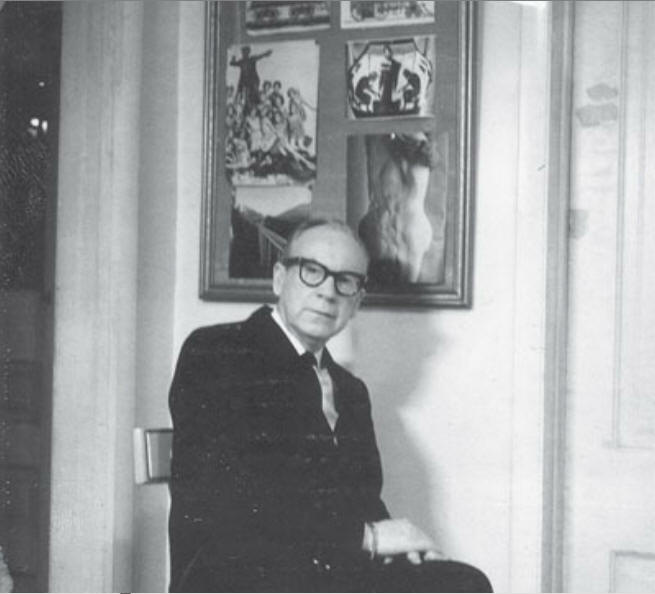

Keith McCutcheon in his house on Jenifer Street in Madison. FROM THE

AUTHOR’S COLLECTION, COURTESY OF TED PIERCE

Because of the bout with tuberculosis, McCutcheon followed his stay at Statesan with a period of convalescence at Statesan’s associated camp at Lake Tomahawk, in the fresh air of the North Woods. There he met Robert Monschein, a young man from Walworth County, and in 1934 they both wrote poems for the institution’s magazine, The Beacon. In that same year Monschein, apparently back in the Walworth area, wrote in a letter to the editor that was published in the Elkhorn paper, “You might be interested to know about the guests which my friend Keith McCutcheon and I have had in the past few months.” He reported that during the summer of 1934, the pair had had several visits from Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who were once accompanied by gay playwright Noel Coward, a frequent visitor to Ten Chimneys, the Lunt-Fontanne summer home in Genesee Depot. The letter also talked about Coward’s play Design for Living, which starred Lunt, Fontanne, and Coward, calling it “a gay sophisticated thing.”

In an October 1935 Rio Journal column, McCutcheon recalled an earlier episode in which the editor of The Badger, the UW yearbook, had invited him to the Loraine Hotel. There, among friends, “sitting carelessly with one leg over the arm of his chair, was Edward Harris Heth.” He described Heth, then also an undergraduate, as an aspiring writer. He told his readers of Heth’s literary career, which McCutcheon had obviously followed, and talked of anticipation about Heth’s upcoming novel Some We Loved.

McCutcheon moved to California in 1939, before the war, to try to break into Hollywood’s film industry, though by the early 1940s he was back in Madison. During the 1930s while still in Madison, he had done radio work, including writing scripts for The Dramatic Hour of the Air, sponsored by the UW on WHA, the university’s radio station. To support himself, McCutcheon began writing a travel column. In September 1939, Wisconsin’s Rio Journal announced that his column would reappear in the paper after a bit of a hiatus. The publishers had “received many compliments” on his material.

In 1941, with the publication of Two Pieces of Venetian Glass, McCutcheon returned to the topic of gay love, for the book is dedicated to his life partner, Edward Joseph "Joe" Koberstein, known as E. J. K. The Capital Times headlined an article about the book, “McCutcheon’s Poetry, Warm, Artistic.” No feminine pronouns were used in this material, which was full of romantic love. Herein McCutcheon spoke of love’s strength built to endure. In the poem “Our Secret,” he wrote, “I could shout it from the housetops, / But who’s the world to hear, / How terribly much I love you.” He described his love as “wild” and “mad.”

Though Madison police raided the Adams Street house on Madison’s west side in 1948 and broke up the homosexual “ring” centered there, they missed the east side’s gay circle, which revolved around the Jenifer Street home of Keith McCutcheon and his partner, Joe Koberstein. Ted Pierce, who was appointed messenger in the Executive Office by Governor Phil La Follette in the 1930s, referred to his gay group on Madison’s east side as a salon of the French order. In later writings, Pierce called it “a magic Group centered on the 700 block of Jenifer Street” that was “lively and highly witty.” Pierce used his connections from Jenifer Street to advocate for civil rights. The African American stage and screen actor Canada Lee, who was a Pierce correspondent, stayed with Pierce when he came to town in 1945.

One Madison couple with connections to the Jenifer Street scene, Bob Lockhart and Clarence Cameron, were introduced by a mutual friend in 1960 when Cameron worked in a funeral home and Lockhart was apprenticing in architecture in Spring Green. The two bonded quickly because, as Lockhart noted, “Part of the spontaneity was because you didn’t know when the police were going to come.” Neither man had figured out he was gay until his twenties; as Lockhart observed, “Goodness sakes, I should have had a little education about this.” Lockhart served in the military in postwar Germany, but Cameron, in an act of self-affirmation, wrote on his induction form, “I’m an active homosexual,” which prevented his military induction. The men recalled, “Even in liberal Madison, police at the time trapped gay men in restrooms and pressured them to confess the names of gay friends, who then often lost their jobs.” Lockhart quietly recalled fifty years later, “We were all closeted.”

My published books: