Partner Suzanne Malherbe, buried together

Queer Places:

Sorbonne, Sorbona, Parigi, Francia

St. Brelade’s Bay Hotel, La Route de la Baie, Jersey

St Brelade, La Marquanderie, Saint Brélade JE3 8LL

Claude

Cahun (25 October 1894 – 8 December 1954), born Lucy Renee Mathilde

Schwob,[1]

was a Jewish-French photographer, sculptor and writer.[2]

Artist Liv Schulman created a series of films: Le Goubernement, a

six-episode fiction imagining the destiny and work of women, lesbian, queer,

trans and non-binary artists who lived in Paris from 1910 – 1980. The episodes

traverses and overlay over 70 years of history and hosts the stories and fate

of artists that were erased from the great twentieth century modernist

narrative including Claude Cahun.

Claude

Cahun (25 October 1894 – 8 December 1954), born Lucy Renee Mathilde

Schwob,[1]

was a Jewish-French photographer, sculptor and writer.[2]

Artist Liv Schulman created a series of films: Le Goubernement, a

six-episode fiction imagining the destiny and work of women, lesbian, queer,

trans and non-binary artists who lived in Paris from 1910 – 1980. The episodes

traverses and overlay over 70 years of history and hosts the stories and fate

of artists that were erased from the great twentieth century modernist

narrative including Claude Cahun.

Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob adopted the gender-ambiguous name Claude Cahun in 1917 and is best known for self-portraits, in which she assumed a variety of personas.

Her work was both political and personal, and often undermined traditional concepts of static gender roles. She once explained: "Under this mask, another mask; I will never finish removing all these faces."

Historical homosocial and homosexual communities of expatriate American and English women lived in Paris on the Left Bank of the Seine during the opening decades of the twentieth century. The place and time has captured the imaginations of feminist and queer historians, literary critics, art historians, and cultural theorists. These histories of women and their cultural productions are attractive because they demand a rethinking and rewriting of the canonical histories of masculine modernism. The geographical and spiritual locus for these groups were the literary and artistic salons of Natalie Barney and Gertrude Stein, as well as the bookshops and publishing houses owned by Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier. Congregating at these cultural landmarks, Janet Flanner, Colette, Renée Vivien, Djuna Barnes, Hilda Doolittle, Claude Cahun, Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Anaïs Nin, and many others invented new ways of living and representing themselves and each other. Martha Vicinus writes: The most striking aspect of the lesbian coteries of the 1910s and 1920s was their self-conscious effort to create a new sexual language for themselves that included not only words but also gestures, costume and behavior. Lillian Faderman notes that these Parisian communities “functioned as a support group for lesbians to permit them to create a self-image which literature and society denied them.”

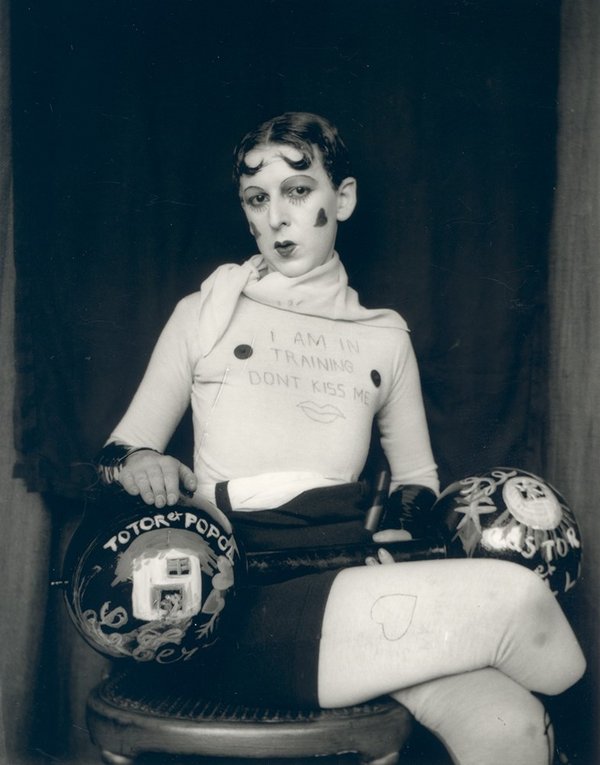

Claude Cahun self portrait c.1927 courtesy Jersey Heritage collections

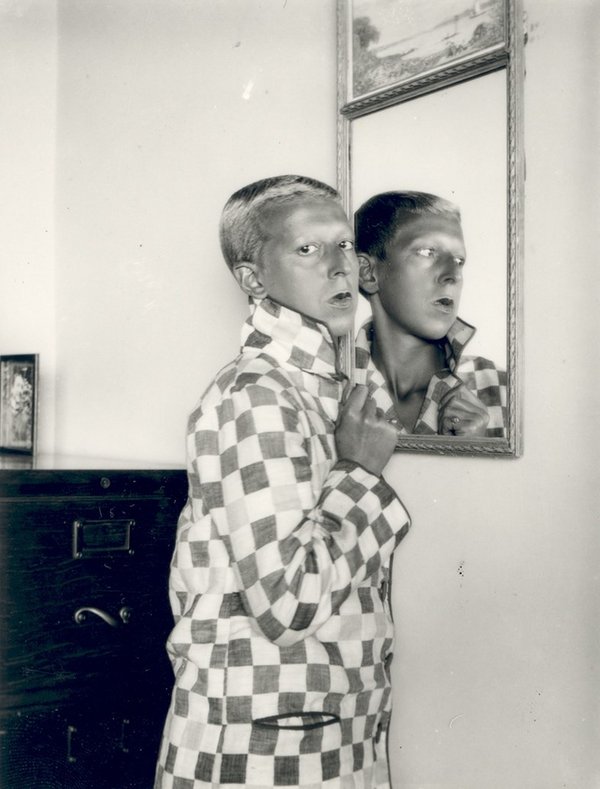

Claude Cahun self portrait c.1928 courtesy Jersey Heritage collections

Born in Nantes in 1894, Cahun was born into a provincial but prominent intellectual Jewish family.[3] Cahun was the niece of an avant-garde writer Marcel Schwob and the great-niece of Orientalist David Léon Cahun. When Cahun was four years old, her mother, Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse, began suffering from mental illness, which ultimately led to her permanent internment at a psychiatric facility.[4] Due to the absence of her mother, Cahun was brought up by her grandmother, Mathilde Cahun.

Cahun attended a private school (Parsons Mead School) in Surrey after experiences with anti-Semitism at her high school in Nantes.[5][6] She attended the University of Paris, Sorbonne.[5]

She began making photographic self-portraits as early as 1912 (aged 18), and continued taking images of herself through the 1930s.

Around 1919, she changed her name to Claude Cahun, after having previously used the names Claude Courlis (after the curlew) and Daniel Douglas (after Lord Alfred Douglas). During the early 1920s, she settled in Paris with her lifelong lesbian partner and step-sibling Suzanne Malherbe, who adopted the pseudonym Marcel Moore.[3]:69 For the rest of their lives together, Cahun and Moore collaborated on various written works, sculptures, photomontages and collages. The two published articles and novels, notably in the periodical Mercure de France, and befriended Henri Michaux, Pierre Morhange, and Robert Desnos.

Around 1922 Claude and Moore began holding artists' salons at their home. Among the regulars who would attend were artists Henri Michaux and André Breton and literary entrepreneurs Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier.[7]

Cahun's works encompassed writing, photography, and theatre. She is most remembered for her highly staged self-portraits and tableaux that incorporated the visual aesthetics of Surrealism. During the 1920s Cahun produced an astonishing number of self-portraits in various guises such as aviator, dandy, doll, body builder, vamp and vampire, angel, and Japanese puppet.[3]:66

Many of Cahun's portraits feature her looking directly at the viewer, with her head shaved, often revealing only her head and shoulders (eliminating the body from view), and a blurring of gender indicators and behaviors which serve to undermine the patriarchal gaze.[8][9]

Her published writings include "Heroines," (1925) a series of monologues based upon female fairy tale characters and intertwining them with witty comparisons to the contemporary image of women; Aveux non avenus, (Carrefour, 1930) a book of essays and recorded dreams illustrated with photomontages; and several essays in magazines and journals.[10]

In 1932 she joined the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she met André Breton and René Crevel. Following this, she started associating with the surrealist group, and later participated in a number of surrealist exhibitions, including the London International Surrealist Exhibition (New Burlington Gallery) and Exposition surréaliste d'Objets (Charles Ratton Gallery, Paris), both in 1936. Cahun's photograph of Sheila Legge standing in the middle of Trafalgar Square with her head obscured by a flower arrangement with pigeons perching on her outstretched arms from the London exhibition, appeared in numerous newspapers and later reproduced in a number of books.[11][12] In 1934, they published a short polemic essay, Les Paris sont Ouverts, and in 1935 took part in the founding of the left-wing anti-fascist alliance Contre Attaque, alongside André Breton and Georges Bataille.[13] Breton called Cahun "one of the most curious spirits of our time."[14]

In 1994 the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London held an exhibition of Cahun's photographic self-portraits from 1927–47, alongside the work of two young contemporary British artists, Virginia Nimarkoh and Tacita Dean, entitled Mise en Scene. In the surrealist self-portraits, Cahun represented themself as an androgyne, nymph, model, and soldier.[15]

In 2007, David Bowie created a multi-media exhibition of Cahun’s work in the gardens of the General Theological Seminary in New York. It was part of a venue called the Highline Festival, which also included offerings by Air, Laurie Anderson, Mike Garson and Ricky Gervais.

Cahun’s work was often a collaboration with Marcel Moore. Cahun and Moore collaborated frequently, though this often goes unrecognized. It is believed that Moore was often the person standing behind the camera during Cahun's portrait shoots and was an equal partner in their collages.[8]

With the majority of the photographs attributed to Cahun coming from a personal collection, not one meant for public display, it has been proposed that these personal photographs allowed for Cahun to experiment with gender presentation and the role of the viewer to a greater degree.[8]

In 1937 Cahun and Moore settled in Jersey. Following the fall of France and the German occupation of Jersey and the other Channel Islands, they became active as resistance workers and propagandists. Fervently against war, the two worked extensively in producing anti-German fliers. Many were snippets from English-to-German translations of BBC reports on the Nazis' crimes and insolence, which were pasted together to create rhythmic poems and harsh criticism. The couple then dressed up and attended many German military events in Jersey, strategically placing them in soldier's pockets, on their chairs, and in cigarette boxes for soldiers to find. Additionally, they inconspicuously crumpled up and threw their fliers into cars and windows. In many ways, Cahun and Moore's resistance efforts were not only political but artistic actions, using their creative talents to manipulate and undermine the authority which they despised. In many ways, Cahun's life's work was focused on undermining a certain authority; however, their activism posed a threat to their physical safety.

In 1944, Cahun and Moore were arrested and sentenced to death, but the sentence was never carried out as the island was liberated from German occupation in 1945.[13] However, Cahun's health never recovered from her treatment in jail, and she died in 1954. She is buried in St Brelade's Church with her lover Marcel Moore.

My published books: