Partner Sylvia Beach

Queer Places:

La Maison des Amis des Livres, 7 Rue de l'Odéon, 75006 Paris, France

18 rue de l’Odéon, 75006,

France

Adrienne Monnier (26 April 1892 – 19 June 1955) was a French bookseller,

writer, and publisher, and an influential figure in the modernist writing

scene in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s.

Adrienne Monnier (26 April 1892 – 19 June 1955) was a French bookseller,

writer, and publisher, and an influential figure in the modernist writing

scene in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s.

Historical homosocial and homosexual communities of expatriate American and English women lived in Paris on the Left Bank of the Seine during the opening decades of the twentieth century. The place and time has captured the imaginations of feminist and queer historians, literary critics, art historians, and cultural theorists. These histories of women and their cultural productions are attractive because they demand a rethinking and rewriting of the canonical histories of masculine modernism. The geographical and spiritual locus for these groups were the literary and artistic salons of Natalie Barney and Gertrude Stein, as well as the bookshops and publishing houses owned by Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier. Congregating at these cultural landmarks, Janet Flanner, Colette, Renée Vivien, Djuna Barnes, Hilda Doolittle, Claude Cahun, Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Anaïs Nin, and many others invented new ways of living and representing themselves and each other. Martha Vicinus writes: The most striking aspect of the lesbian coteries of the 1910s and 1920s was their self-conscious effort to create a new sexual language for themselves that included not only words but also gestures, costume and behavior. Lillian Faderman notes that these Parisian communities “functioned as a support group for lesbians to permit them to create a self-image which literature and society denied them.”

Monnier was born in Paris on 26 April 1892.[1] Her father, Clovis Monnier (1859–1944), was a postal worker (postier ambulant), sorting mail in transit on night trains.[2][1] Her mother, Philiberte (née Sollier, 1873–1944), was "open-minded" with an interest in literature and the arts.[2][1] Adrienne's younger sister, Marie (1894–1976), would become known as a skillful embroiderer and illustrator.[3][1] Their mother encouraged the sisters to read widely from an early age and frequently took them to the theatre, opera, and ballet.[1]

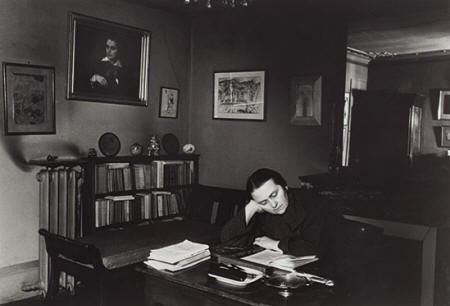

Adrienne Monnier, 1938, by Gisèle Freund

Adrienne Monnier, 1935, by Gisèle Freund

James Joyce with Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, 1938, , by Gisèle

Freund

In 1909, aged 17, Monnier graduated from high school, with a teaching qualification (brevet supérieur).[4] Within months, in September, she moved to London, officially to improve her English but in reality to be close to her classmate, Suzanne Bonnierre, with whom she was "very much in love".[4][5] Monnier spent three months working as an au pair, before finding a job for six months teaching French in Eastbourne.[4] She later wrote about her English experiences in Souvenirs de Londres ("Memories of London").

Back in France, Monnier taught briefly at a private school, before enrolling on a shorthand and typing course.[4] Thus equipped, in 1912, she found work as a secretary at the Université des Annales, a Right Bank publishing house specialising in mainstream literary and cultural works. Although Monnier enjoyed the work, she had little in common with the writers and journalists with whom she came into contact, preferring the bohemian Left Bank and the avant-garde literary world that it represented.[4]

In November 1913, Monnier's father, Clovis, was seriously injured in a train crash while at work; he was left with a lifelong limp.[6] When the compensation came through, he gave all of it – 10,000 Francs – to Monnier, to help her set up in bookselling.[6]

On 15 November 1915, Monnier opened her bookshop and lending library, "La Maison des Amis des Livres" [7] at 7 rue de l'Odéon, Paris VI.[6] She was among the first women in France to found her own book store. While women sometimes assisted in a family bookstore, and widows occasionally took over their husband’s bookselling or publishing business, it was unusual for a French woman to independently set herself up as a bookseller. Nonetheless Monnier, who had worked as a teacher and as a literary secretary, loved the world of literature and was determined to make bookselling her career. With limited capital she opened her shop at a time when there was a genuine need for a new book store, since many book sellers had left their work to join the armed forces. As her reputation spread, Monnier's advice was sought out by other women who hoped to follow her example and become booksellers.

Monnier offered advice and encouragement to Sylvia Beach when Beach founded an English language bookstore called Shakespeare and Company in 1919.[8] During the 1920s, the shops owned by Beach and Monnier were located across from each other on the rue de l'Odéon in the heart of the Latin Quarter. Both bookstores became gathering places for French, British, and American writers. By sponsoring readings and encouraging informal conversations among authors and readers, the two women brought to bookselling a domesticity and hospitality that encouraged friendship as well as cultural exchange.

Only a few months after the opening of Shakespeare and Company, a sudden death changed the relationship that had until then existed between Sylvia and Adrienne. Not a year after her marriage to Gustave Tronche, the administrator for publications of the Nouvelle Revue Française, Suzanne Bonnierre—who, Adrienne admitted, had never returned Adrienne’s love in the measure that it was given—died suddenly. Sometime in the months following Suzanne’s death, the two women became lovers. Suzanne Bonnierre’s death may well have forced them to acknowledge their attraction for each other. Gertrude Stein, who might have sensed the tensions of sexual attraction in this relationship, posed the question in “Rich and poor in English,” “do you care for Suzanne?” Within a few months Sylvia moved in with Adrienne in her apartment at 18, rue de l’Odéon, a residence she kept until 1937.

In June 1925, Monnier, with Beach's moral and literary support, launched a French language review, Le Navire d'Argent (The Silver Ship), with Jean Prévost as literary editor.[9] Taking its name from the silver sailing ship, which appears in Paris's coat of arms,[10] it cost 5 Fr per issue, or 50 Fr for a twelve-month subscription. Although financially unsuccessful, it was an important part of the literary scene of the Twenties and was "a great European light", helping launch several writers' careers.[10] Typically, about a hundred pages per issue, it was "French in language, but international in spirit" and drew heavily on the circle of writers frequenting her shop.[10] The first edition contained a French-language translation (prepared jointly by Monnier and Beach) of T. S. Eliot's poem, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (May 1925). Other issues included an early draft of part of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake (Oct 1925); and an abridged version of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's novella, The Aviator, in the penultimate (April 1926) edition. One edition (March 1926) was devoted to American writers (including Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams and E. E. Cummings).[9] It also first introduced Ernest Hemingway in translation to French audiences.[9] Monnier herself contributed under the pseudonym J-M Sollier, based on her mother's maiden name.[11] After twelve issues, Monnier abandoned the Navire d’Argent, as the effort and the cost was more than she could manage.[9] To cover her losses, Monnier auctioned her personal collection of 400 books, many inscribed to her by their authors.[12][13] A decade later, Monnier launched a successor periodical, the Gazette des Amis des Livres, which ran from January 1938 until May 1940.[11]

In 1935, Andre Malraux invited Gisèle Freund to document First International Congress in Defence of Culture in Paris, where she was introduced to and subsequently photographed many of the notable French artists of her day.[6] Freund befriended Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier. In 1935, Monnier arranged a marriage of convenience for Freund with Pierre Blum so that Freund could obtain a visa to remain in France legally (they officially divorced after the war in 1948).

Sylvia was to face such a crisis in 1937. She left Paris in July to visit her father on his eighty-fourth birthday, her first return to America in twenty-two years. Returning from her California visit to the east coast, she became ill and learned that she must undergo a hysterectomy, which required several weeks of rest before her doctor allowed her to return to Paris. When she did finally return to the rue de l’Odéon in mid-October, she discovered that she had been replaced in Adrienne’s apartment by Gisèle Freund, the young German photographer. The previous winter, Gisèle—who had been ordered out of France and who had no passport to return to Germany—was taken in by Adrienne and Sylvia and spent increasingly more time with the two women. Adrienne helped her make a “marriage of convenience” to a Frenchman in order to continue living in the country. Whatever the reasons for the move to 18, rue de l’Odéon, Gisèle Freund represented a threat to Sylvia’s relationship with Adrienne, and the evidence suggests that in her absence Adrienne had replaced Sylvia with a younger lover. Within days of her return Sylvia had moved into the rooms above Shakespeare and Company; although she still took her meals with Adrienne and Gisèle (there being no proper kitchen in her own apartment) and continued her professional relationship with Adrienne, their long standing union had effectively been terminated.

Gisèle Freund was forced to leave Paris with the advance of the Germans in 1940, but Adrienne and Sylvia did not take up their former intimacy. Each stayed in her apartment; each continued her professional life. Sylvia closed her bookshop in December 1941, after an unpleasant incident with a German officer who wanted to buy her only copy of Finnegans Wake, which she had displayed in the window. The officer threatened to confiscate her books; with the help of friends, Sylvia moved the books four flights above the bookshop premises, removed the shelves, and had the name of the shop painted over. Within a few hours, Shakespeare and Company no longer existed. In July 1942, Sylvia was taken to an internment camp south of Paris.

Although Beach closed her store during the German Occupation, Monnier remained open and continued to provide books and solace to Parisian readers. Although Beach returned to live in number 12, rue de l’Odéon, after the war, she never reopened Shakespeare and Company. For ten years after the war Adrienne Monnier continued her work as an essayist, translator and bookseller. Plagued by ill health, Monnier was diagnosed in September 1954 with Ménière's disease, a disorder of the inner ear which affects balance and hearing.[14] Further, she also suffered from delusions. On 19 June 1955, she committed suicide by taking an overdose of sleeping pills.[14]

My published books: