Queer Places:

21 Place Vendôme, 75001 Paris, France

Cimetière Saint Eloi

Frucourt, Departement de la Somme, Picardie, France

Elsa

Schiaparelli (September 10, 1890 – November 13, 1973) was an Italian fashion

designer. Along with Coco

Chanel, her greatest rival, she is regarded as one of the most prominent

figures in fashion between the two World Wars.[5]

Starting with knitwear, Schiaparelli's designs were heavily influenced by

Surrealists like her collaborators Salvador Dalí and

Jean Cocteau.

Her clients included the heiress

Daisy Fellowes and

actress Mae West. Schiaparelli did not adapt to the changes in fashion

following World War II and her couture house closed in 1954.

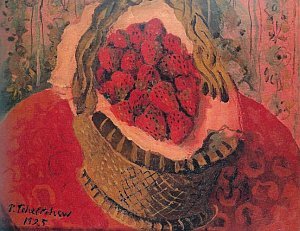

Elsa Schiaparelli said that the

inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Pavel Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

Elsa

Schiaparelli (September 10, 1890 – November 13, 1973) was an Italian fashion

designer. Along with Coco

Chanel, her greatest rival, she is regarded as one of the most prominent

figures in fashion between the two World Wars.[5]

Starting with knitwear, Schiaparelli's designs were heavily influenced by

Surrealists like her collaborators Salvador Dalí and

Jean Cocteau.

Her clients included the heiress

Daisy Fellowes and

actress Mae West. Schiaparelli did not adapt to the changes in fashion

following World War II and her couture house closed in 1954.

Elsa Schiaparelli said that the

inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Pavel Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

Elsa Luisa Maria Schiaparelli was born at the Palazzo Corsini, Rome.[6]

Her mother, Maria-Luisa, was a Neapolitan aristocrat.[7]

Her father, Celestino Schiaparelli, was an accomplished scholar with multiple

areas of interest. The cultural background and erudition of her family members

served to ignite the imaginative faculties of Schiaparelli's impressionable

childhood years. She became enraptured with the lore of ancient cultures and

religious rites. These sources inspired her to pen a volume of poems titled

Arethusa based on the ancient Greek myth of the hunt. The content of her

writing so alarmed the conservative sensibilities of her parents they sought

to tame her fantasy life by sending her to a convent boarding school in

Switzerland. Once within the school's confines, Schiaparelli rebelled against

its strict authority by going on a hunger strike, leaving her parents to see

no alternative but to bring her home again.[11]

Schiaparelli was dissatisfied by a lifestyle that whilst refined and

comfortable, she considered cloistered and unfulfilling. Her craving for

adventure and exploration of the wider world led to her taking measures to

remedy this, and when a friend offered her a post caring for orphaned children

in an English country house, she saw an opportunity to leave. The placement

however, proved uncongenial to Schiaparelli, who subsequently planned a return

to the stop-over city of Paris rather than admit defeat by returning to Rome

and her family.[12]

Strawberries by Pavel Tchelitchew

Schiaparelli fled to London to avoid the certainty of marriage to a

persistent suitor, a wealthy Russian whom her parents favored and for whom she

herself felt no attraction. In London, Schiaparelli who had held a fascination

for psychic phenomena since childhood, attended a lecture on theosophy. The

lecturer that night was Willem de Wendt, a man of various aliases who was also

known as Willie Wendt and Wilhem de Kerlor. Schiaparelli was immediately

attracted to this charismatic charlatan and they became engaged on the very

next day of their first meeting. They married shortly thereafter in London on

July 21, 1914, Schiaparelli was twenty-three, her new husband thirty.[15]

de Kerlor attempted to earn a living aggrandizing his reputation as a psychic

practitioner as the couple subsisted primarily on the wedding dowry and an

allowance provided by Schiaparelli's wealthy parents.[16]

Schiaparelli played the role of her husband's helpmate and helped facilitate

the promotion of his fraudulent schemes. In 1915 the couple were forced to

leave England after de Kerlor was deported following his conviction for

practicing fortune-telling, then illegal.[17]

They subsequently lived a peripatetic existence in Paris, Cannes, Nice, and

Monte Carlo, before leaving for America in the spring of 1916.

The de Kerlors disembarked in New York, initially staying at the Brevoort,

a prominent hotel in Greenwich Village, then relocated to an apartment above

the Café des Artistes near Central Park West. De Kerlor rented offices to

house his newly inaugurated "Bureau of Psychology" where he hoped to achieve

fame and fortune through his paranormal and consulting work. His wife acted as

his assistant, providing clerical support for self-promotions crafted to

provide the newspapers with sensational copy, win celebrity and garner

acclaim. During this period de Kerlor came under the surveillance of the

Federal government's Bureau of Investigation, (BOI) a precursor of the Federal

Bureau of Investigation, (FBI), not only for his dubious professional

practices but also on suspicion of harboring anti-British and pro-German

allegiance during wartime. By 1917, de Kerlor's acquaintance with journalists

John Reed and Louise Bryant had positioned him on the government radar as a

possible Bolshevik sympathizer and Communist revolutionary. Attempting to

avoid this unremitting scrutiny, the de Kerlors decamped to Boston in 1918,

where they continued their activities as they had done in New York.[18]

De Kerlor, an incurable publicity hound, made imprudent admissions to a BOI

investigator in prideful support of the Russian Revolution and went so far as

to admit to an association with a notorious anarchist, whilst his wife

incriminated herself by revealing that she was tutoring Italians in Boston's

North End on the tenets of Bolshevism and that she herself had the knowledge

to assemble explosive devices. Both were ultimately spared prosecution or

deportation, the authorities concluding that such admissions so freely given

were more indicative of foolish grandstanding than evidence of individuals who

were a threat to society.[19]

Almost immediately after their child, Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha (nicknamed

'Gogo'), was born on June 15, 1920, de Kerlor moved out leaving Schiaparelli

alone with their newborn daughter.[20]

In later years, whenever Gogo asked her mother about her absent father, she

was told that he was dead.[21]

Schiaparelli apparently made no efforts to bring her husband back or to seek

support payments for herself and Gogo.[21]

In 1921, the 18-month-old Gogo was diagnosed with polio, which proved a

stressful and protracted challenge for both mother and child. Years later Gogo

recalled spending her early years in plaster casts and on crutches, with a

largely absent mother whom she barely saw. Fearing that de Kerlor would

attempt to gain legal custody of Gogo, Schiaparelli had the child's surname

legally changed to Schiaparelli prior to their return to France in 1922.[22]

Schiaparelli relied greatly on the emotional support offered her by her

close friend Gabrielle 'Gaby' Buffet-Picabia, the wife of Dada/Surrealist

artist Francis

Picabia, whom she had first met on board ship during the

transatlantic crossing to America in 1916.[23]

Following de Kerlor's desertion, Schiaparelli returned to New York, attracted

to its spirit of fresh beginnings and cultural vibrancy. Her interest in

spiritualism translated into a natural affinity for the art of the Dada and

Surrealist movements, and her friendship with Gaby Picabia facilitated entry

into this creative circle which comprised noteworthy members such as

Man Ray,

Marcel Duchamp,

Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen.[24]

Although technically still married, Schiaparelli took a lover, the opera

singer Mario Laurenti, but this relationship was cut short after Laurenti's

death in 1922 after a sudden illness.[25]

Whilst they were together, de Kerlor had purportedly conducted affairs with

the dancer

Isadora Duncan and the actress

Alla Nazimova.[25]

Schiaparelli and de Kerlor were eventually divorced in March 1924.[26]

In 1928, de Kerlor was murdered in Mexico under circumstances never fully

revealed.[21]

Following the lead of Gabrielle Picabia and others, and after the death of

her lover Laurenti, Schiaparelli left New York for France in 1922. Upon her

arrival in Paris, she took an expensive apartment in a fashionable quarter of

the city taking on the requisite servants, cook and maid. The self-made

associations she formed over the years along with the eminent social position

held by her Italian family combined to ensure that she would be embraced by

desirable social circles on her return to France.[27]

Although never threatened with destitution as she continued to receive

financial support from her mother, Schiaparelli nevertheless felt the need to

earn an independent income. She assisted Man Ray with his Dada magazine

Société Anonyme, which proved short lived. Gaby Picabia then suggested a

business enterprise which would be beneficial to herself and Schiaparelli.

Connected to the French couturier Paul Poiret through her association with his

sister Nicole Groult, Picabia proposed that they sell French couture in

America. This proposed project, however, never became a viable enterprise and

was abandoned.[28]

Schiaparelli's design career was early on influenced by couturier Paul

Poiret, who was renowned for jettisoning corseted, over-long dresses and

promoting styles that enabled freedom of movement for the modern, elegant and

sophisticated woman. In later life, Schiaparelli referred to Poiret as "a

generous mentor, dear friend."[29]

Schiaparelli had no training in the technical skills of pattern making and

clothing construction. Her method of approach relied on both impulse of the

moment and the serendipitous inspiration as the work progressed. She draped

fabric directly on the body, sometimes using herself as the model. This

technique followed the lead of Poiret who too had created garments by

manipulating and draping. The results appeared uncontrived and wearable.

Whilst in Paris, Schiaparelli - "Schiap" to her friends - began making her

own clothes. With encouragement from Poiret, she started her own business but

it closed in 1926 despite favourable reviews.[6]

She launched a new collection of knitwear in early 1927 using a special double

layered stitch created by Armenian refugees and featuring sweaters with

surrealist trompe l'oeil images.[6]

Although her first designs appeared in Vogue, the business really took

off with a pattern that gave the impression of a scarf wrapped around the

wearer's neck.[6]

The "pour le Sport" collection expanded the following year to include bathing

suits, ski-wear, and linen dresses. Schiaparelli added evening wear to her

collections in 1931, using the luxury silks of Robert Perrier, and the

business went from strength to strength, culminating in a move from Rue de la

Paix to acquiring the renowned salon of Louise Chéruit at 21 Place Vendôme,

which was rechristened the Schiap Shop.[6][30]

Colin McDowell noted that by 1939 Schiaparelli was well known enough in

intellectual circles to be mentioned as the epitome of modernity by the Irish

poet Louis MacNeice. Although McDowell cites MacNeice's reference as from

Bagpipe Music,[32][33]

it is actually from stanza XV of Autumn Journal.[31]

A darker tone was set when France declared war on Germany in 1939.

Schiaparelli's Spring 1940 collection featured "trench" brown and camouflage

print taffetas.[6]

Soon after the fall of Paris on 14 June 1940, Schiaparelli sailed to New York

for a lecture tour; apart from a few months in Paris in early 1941, she

remained in New York City until the end of the war.[6]

On her return she found that fashions had changed, with Christian Dior's "New

Look" marking a rejection of pre-war fashion. The house of Schiaparelli

struggled in the austerity of the post-war period. Schiaparelli discontinued

her couture business in 1951, and finally closed down the heavily indebted

design house in December 1954,[34][6]

the same year that her great rival Coco Chanel returned to the business.

In 1954, Schiaparelli published her autobiography Shocking Life and

then lived out a comfortable retirement between her Paris apartment and house

in Tunisia. She died on 13 November 1973 at the age of 83.

Schiaparelli's two granddaughters, from her daughter's marriage to shipping

executive Robert L. Berenson, were model Marisa Berenson and photographer

Berry Berenson. Both sisters appeared regularly in Vogue in the early 1970s.

Berry was married to the actor

Anthony Perkins,

with whom she had two children, the actor Oz Perkins and the musician Elvis

Perkins. In 2014, Marisa collaborated with

Givenchy to publish the book Elsa Schiaparelli’s Private

Album which reproduced photographs from her grandmother's personal

archives.[76]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elsa_Schiaparelli

Elsa

Schiaparelli (September 10, 1890 – November 13, 1973) was an Italian fashion

designer. Along with Coco

Chanel, her greatest rival, she is regarded as one of the most prominent

figures in fashion between the two World Wars.[5]

Starting with knitwear, Schiaparelli's designs were heavily influenced by

Surrealists like her collaborators Salvador Dalí and

Jean Cocteau.

Her clients included the heiress

Daisy Fellowes and

actress Mae West. Schiaparelli did not adapt to the changes in fashion

following World War II and her couture house closed in 1954.

Elsa Schiaparelli said that the

inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Pavel Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

Elsa

Schiaparelli (September 10, 1890 – November 13, 1973) was an Italian fashion

designer. Along with Coco

Chanel, her greatest rival, she is regarded as one of the most prominent

figures in fashion between the two World Wars.[5]

Starting with knitwear, Schiaparelli's designs were heavily influenced by

Surrealists like her collaborators Salvador Dalí and

Jean Cocteau.

Her clients included the heiress

Daisy Fellowes and

actress Mae West. Schiaparelli did not adapt to the changes in fashion

following World War II and her couture house closed in 1954.

Elsa Schiaparelli said that the

inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Pavel Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.