Partner Allen C. Tanner, Charles Henri Ford

Queer Places:

360 E 55th St, New York, NY 10022

Weston, CT 06883, Stati Uniti

Père Lachaise Cemetery, 16 Rue du Repos, 75020 Paris, Francia

Campo Cestio, Via Caio Cestio, 6, 00153 Roma RM, Italia

Pavel

Tchelitchew (21 September 1898, Kaluga,[1]

near Moscow – 31 July 1957, Rome) was a Russian-born surrealist painter, set

designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to an aristocratic family

of landowners and was educated by private tutors.[2]

Tchelitchew expressed an early interest in

ballet and

art.[3]

He left Russia in 1920, lived in Berlin from 1921 to 1923, and moved to Paris

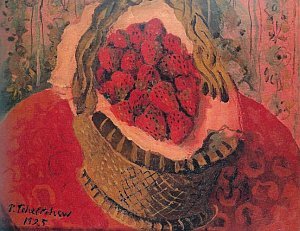

in 1923. Elsa Schiaparelli

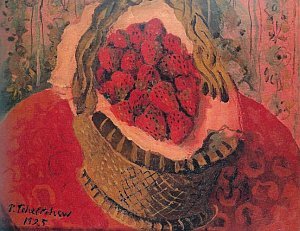

said that the inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

Pavel

Tchelitchew (21 September 1898, Kaluga,[1]

near Moscow – 31 July 1957, Rome) was a Russian-born surrealist painter, set

designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to an aristocratic family

of landowners and was educated by private tutors.[2]

Tchelitchew expressed an early interest in

ballet and

art.[3]

He left Russia in 1920, lived in Berlin from 1921 to 1923, and moved to Paris

in 1923. Elsa Schiaparelli

said that the inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

In 1922, Allen C. Tanner

left for Berlin, where he met Tchelitchew and the two men became lovers. In

1923 the pair moved to Paris to pursue their artistic careers.

In the winter of 1923 composer Nicolas Nabokov, cousin to

Vladimir and

Sergei, introduced Sergei to Tchelitchev.

The two of them shared an apartment with Tanner. The flat was so tiny that

when Tchelitchev saw it he remarked, "We are to live in a doll's house!" It

had no electricity and no bath -- they had to wash themselves in a zinc tub

using water heated on a gas stove. Sergei survived by giving lessons in

English and Russian. His circumstances may have been straitened, but the

cultural scene in which Sergei found himself was rich beyond all measure.

According to Andrew Field, Nabokov's first biographer, Sergei was good friends

with Jean Cocteau, and he was also

connected, through Tchelitchev and his cousin Nicolas, to

Sergei Diaghilev,

to composer Virgil Thomson, to

those aristocratic aesthetes the Sitwells and even to the legendary salons

conducted by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas at 27 Rue de Fleurus.

In Paris Tchelitchew became acquainted with

Gertrude Stein and,

through her, the Sitwell and Gorer families. He and

Edith Sitwell had a

long-standing close friendship and they corresponded frequently.

by Carl Van Vechten

by

George Platt Lynes

George Platt Lynes & Pavel Tchelitchev

by Pavel Tchelitchew

Lotte Lenya, 1929, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Rene Crevel, by Pavel Tchelitchew

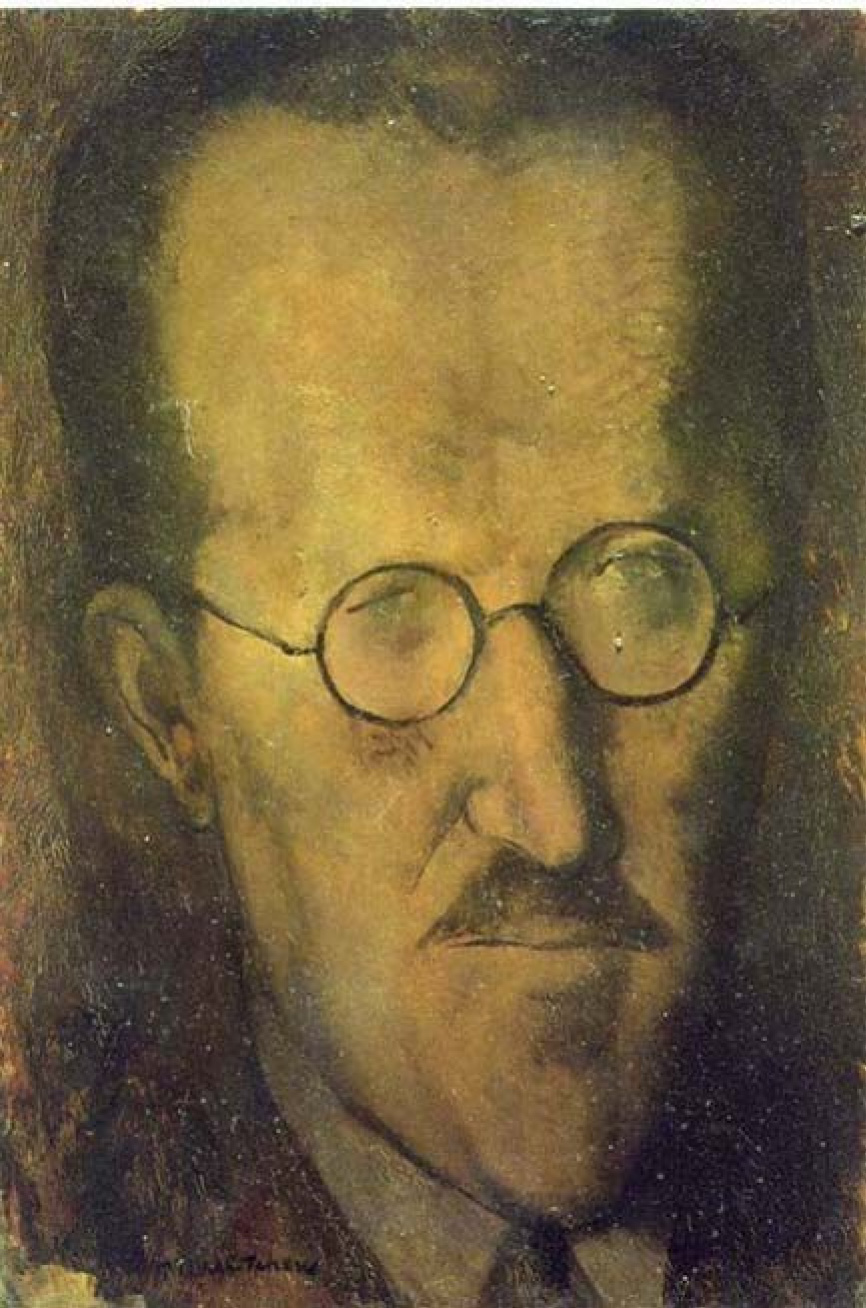

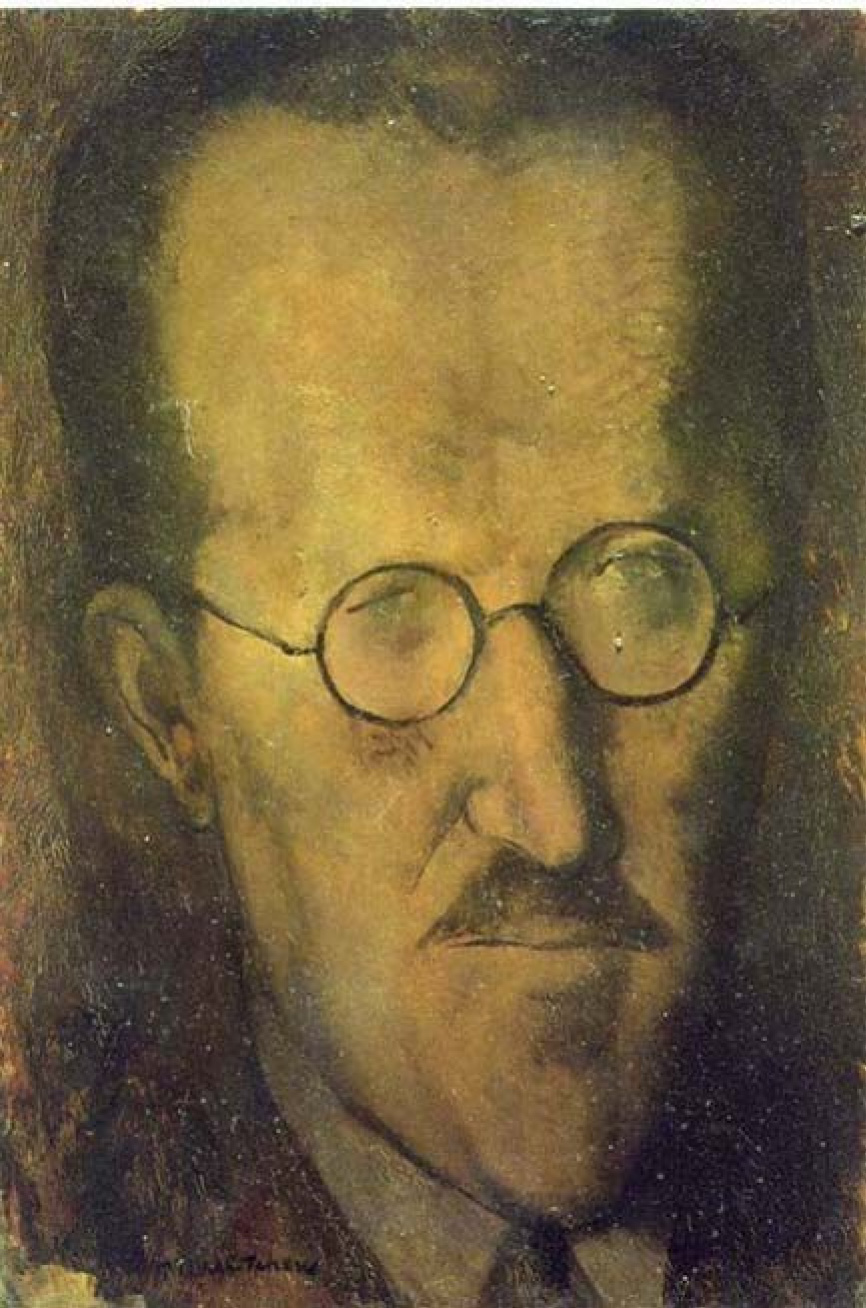

James Joyce, 1929, by Pavel Tchelitchew

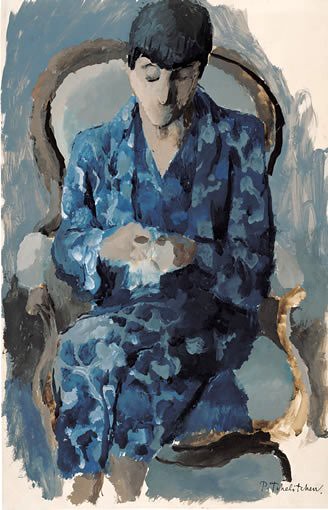

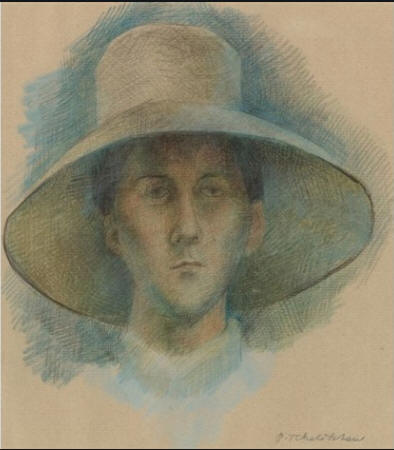

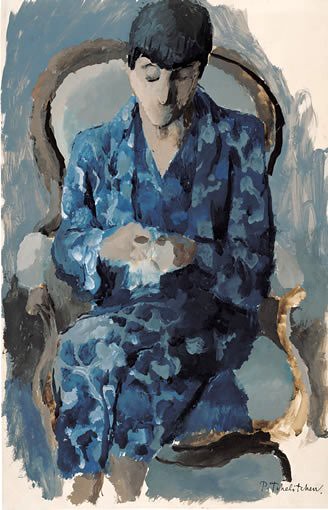

Alice B. Toklas, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Edith Sitwell, by Pavel Tchelitchew

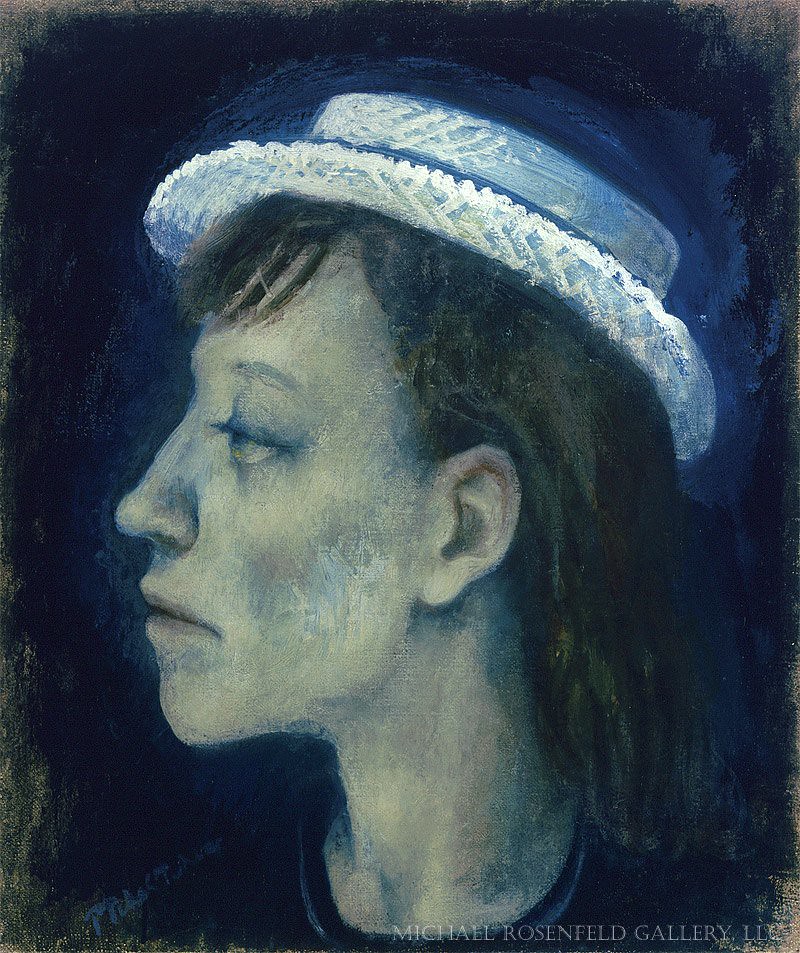

Tilly Losch, 1933, by Pavel Tchelitchew

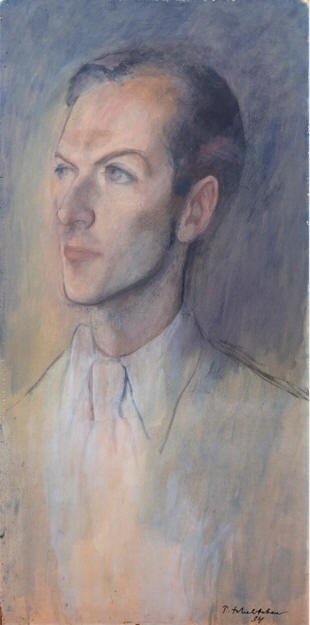

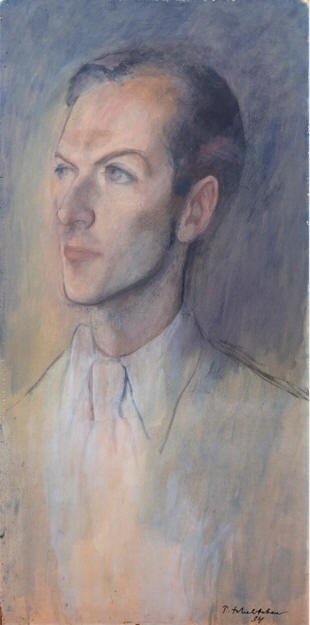

Cecil Beaton, 1934, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Allen Tanner, by Pavel Tchelitchew

George Platt Lynes, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Charles Henri Ford, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Lincoln Kirstein, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Strawberries by Pavel Tchelitchew

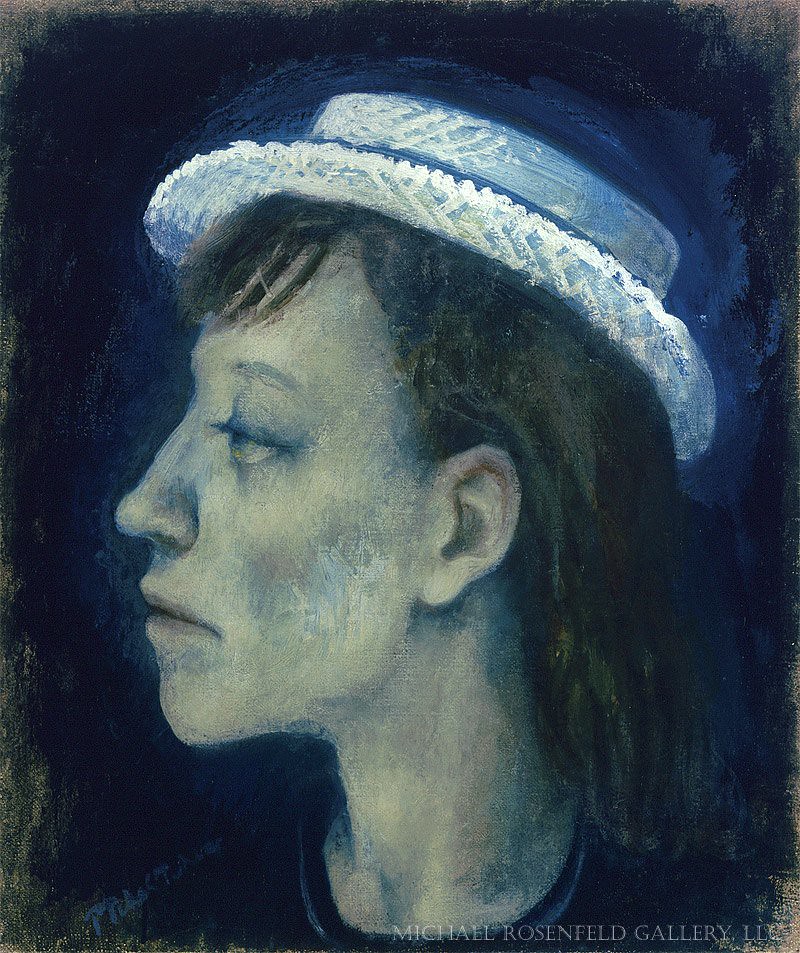

Pavel Tchelitchew

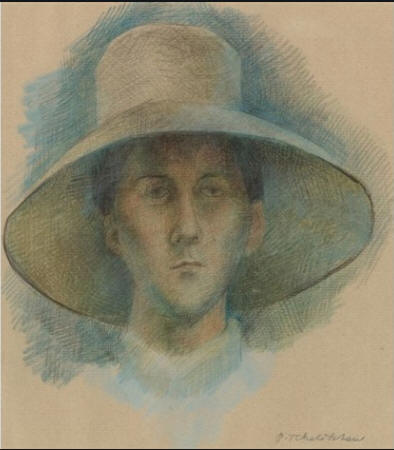

Portrait of a Peggy O'Brien in a Beret, 1937

Back in Paris again in the spring of 1926,

Klaus Mann met

René Crevel, a committed internationalist for

perverse reasons: "He spent his days with Americans, Germans, Russians, and

Chinese, because his mother suspected all foreigners to be crooks or

perverts". Sitting on Mann’s bed, Crevel read out the early chapters of his

novel La Mort difficile, with their "venomous" portrait of his mother. On this

trip, Mann also met Jean Cocteau

("The hours spent in his company assume in my recollection a savour both of

burlesque show and magic ritual"),

Eugene McCown, Pavel Tchelitchew,

Julien Green,

Jean Giraudoux and others.

His first U.S. show was of his drawings, along with other artists, at the

newly opened Museum of Modern Art in 1930. In 1934, he moved from Paris to New

York City with his partner, writer

Charles Henri

Ford. Charles Henri Ford and Pavel Tchelitchew had a guest house on the

estate of Alice De Lamar. A

probable influence of Mark Tobey was

Tchelitchew, who created several images, such as The Thinker of 1927, in which

the figure (usually male) is contained in a series of weblike lines. It is

very likely that Tobey either personally knew or at least knew of Tchelitchew

through his circle of artist friends while living in New York in the early

1930s. Coincidentally, Tobey's "white writing" development began right after

Tchelitchew's first American exhibition at New York's

Julien Levy Gallery in 1934.

From 1940 to 1947, he provided illustrations for the Surrealist

magazine View, edited by Ford and writer and film critic

Parker Tyler. His most

significant work is the painting Hide and Seek, painted in 1940–42, and

currently owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Ruth Ford’s connection to

William Faulkner did not begin

in October 1948, though her actions during Faulkner’s lost weekend lionized

her presence in his life. Ford entered Faulkner’s life much earlier, as a coed

at the University of Mississippi in 1929–1930. A native of Hazlehurst,

Mississippi, Ford attended Ole Miss at approximately the same time as

Faulkner’s brother, Dean. Estelle claimed that Dean and Ford dated and that

Dean, a talented painter, had Estelle and Ford sit for him. Victoria

(Cho-Cho), barely a teenager at the time, disputed that any relationship

existed between Dean and Ford, but Estelle would tell in 1963 that this

relationship, though it “never became truly serious apparently,” is why

Faulkner not only wrote Requiem for a Nun for Ford, but also why he gave her

the stage rights with very little requirement on her part for payments to

option it until it finally appeared ten years after his initial offer. Ford

told that Dean introduced her to his brother, a struggling writer at the time.

Barbara Izard, whose work on the history of the production of Requiem also

serves as a biography of Ford, recounts, however, that Faulkner introduced

himself to Ford, roughly around the time he was composing As I Lay Dying.

According to Izard, Faulkner approached Ford in the local Oxford landmark, the

Tea Hound, to tell her “‘You have a very fine face,’ Then without further

comment, he turned and went back to his table”. In 1948 Ford was living in New

York and working in Broadway productions but traveling often to Boston to work

for the Brattle Theater Company, where, in the early 1950s, she would first

attempt to stage Requiem with the help of her brother’s lover as the set

designer. The novel was published in 1951. On 15 September 1951, the New York

Times announced that Faulkner was working with producer Lemuel Ayers on a

stage version of the play to feature Ruth Ford, whom, according to the

columnist, Faulkner “had in mind for his leading feminine character.”

Unfortunately, the production was profoundly delayed. Albert Marre, who was

supposed to direct the production in 1951, would cite trouble between Ford’s

vision and the Brattle’s interests as the source of the problem. Ford insisted

that her brother’s partner, Pavel

Tchelitchew, be the set designer. According to Marre, in the spring of

1952 Tchelitchew, Ford’s brother

Charles Henri-Ford, and

Ford had a falling out over their creative differences, which led to the death

of this first attempt at producing a stage version of the play. Concerning all

this theater drama, Marre claimed that “William Faulkner didn’t concern

himself” with Ford’s decision to turn over set design to her brother’s

homosexual partner. The creative differences, however, were between the

management of the Brattle Theater Company and the Fords (including Charles’s

life partner Pavel), not between Ford and Tchelitchew. Indeed, Faulkner had

surely met both Tchelitchew and Charles Henri-Ford during his frequent trips

to New York from 1948 to 1952, most likely at the famed social gatherings

hosted by the couple in their apartment. Izard charts the history of the

weekly salons hosted in Henri-Ford’s apartment in the New York landmark, the

Dakota, where Ruth Ford would also live until her death in 2009. Though these

salons originally started as low-key gatherings of friends, they eventually

“included Salvador Dali, Carl

Van Vechten, William

Carlos Williams, John Huston, and

Virgil Thomson”. Modeled after

the weekly salons that Gertrude Stein

and Alice B. Toklas hosted in

Paris, which Henri-Ford had attended in the early 1930s, these salons became

legendary, so much so that in her memoir Just Kids

Patti Smith would lament that by the time she

attended the salon in the 1970s, it had lost the luster that made her so

excited to attend in the first place. Faulkner had the luxury of attending the

salon in its prime. There he would have met Henri-Ford, the young pioneer of

surrealism whose first novel, written with his homosexual friend

Parker Tyler, stands as one of the original

novels of the gay genre in American literature, The Young and the Evil (1933).

The reputation of that novel would precede it, having been praised by no less

than Djuna Barnes and Gertrude

Stein.

He became a United States citizen in 1952 and died in Grottaferrata, Italy

in 1957. He is interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Tchelitchew's early painting was abstract in style, described as

Constructivist and Futurist and influenced by his study with Aleksandra Ekster

in Kiev. After emigrating to Paris he became associated with the

Neo-romanticism movement. He continuously experimented with new styles,

eventually incorporating multiple perspectives and elements of surrealism and

fantasy into his painting. As a set and costume designer, he collaborated with

Sergei Diaghilev

and George

Balanchine, among others.

Among Tchelitchew's well-known paintings are portraits of Natalia Glasko,

Edith Sitwell and

Gertrude Stein and

the works Phenomena (1936–1938) and Cache Cache (1940–1942).

Tchelitchew designed sets for Ode (Paris, 1928), L'Errante (Paris, 1933),

Nobilissima Visione (London, 1938) and Ondine (Paris, 1939).[4]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavel_Tchelitchew

- https://www.salon.com/control/2000/05/17/nabokov_5/

-

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/gregory-woods-the-influence-of-homosexuality-on-western-culture-a6980451.html

-

Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

-

Hidden Histories, 20th Century Male Same Sex Lovers in the Visual Arts, by

Michael Petry

-

Gordon, Phillip. Gay Faulkner (pp.215-216). University Press of

Mississippi. Edizione del Kindle.

Pavel

Tchelitchew (21 September 1898, Kaluga,[1]

near Moscow – 31 July 1957, Rome) was a Russian-born surrealist painter, set

designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to an aristocratic family

of landowners and was educated by private tutors.[2]

Tchelitchew expressed an early interest in

ballet and

art.[3]

He left Russia in 1920, lived in Berlin from 1921 to 1923, and moved to Paris

in 1923. Elsa Schiaparelli

said that the inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.

Pavel

Tchelitchew (21 September 1898, Kaluga,[1]

near Moscow – 31 July 1957, Rome) was a Russian-born surrealist painter, set

designer and costume designer. Tchelitchew was born to an aristocratic family

of landowners and was educated by private tutors.[2]

Tchelitchew expressed an early interest in

ballet and

art.[3]

He left Russia in 1920, lived in Berlin from 1921 to 1923, and moved to Paris

in 1923. Elsa Schiaparelli

said that the inspiration for her "shocking pink" came from Tchelitchew's

painting Strawberries.