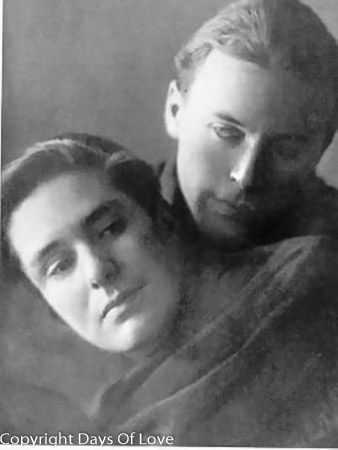

Husband W.H. Auden, Partner Therese Giehse

Queer Places:

Alte Landstrasse 39, 8802 Kilchberg, Switzerland

Kilchberg Village Cemetery, Kilchberg, Svizzera

Erika

Julia Hedwig Mann (November 9, 1905 – August 27, 1969) was a German actress

and writer. She was the eldest daughter of the novelist

Thomas Mann and his wife

Katia.

Erika

Julia Hedwig Mann (November 9, 1905 – August 27, 1969) was a German actress

and writer. She was the eldest daughter of the novelist

Thomas Mann and his wife

Katia.

In 1924, Erika Mann moved to Berlin where she lived a bohemian lifestyle and became a critic of National Socialism. She acted in, and wrote for, an anti-Nazi cabaret in Berlin and, after Hitler came to power in 1933, Mann moved to Switzerland. In 1935 she married the poet W. H. Auden, purely to ensure she could obtain a British passport and not become stateless when the Nazi regime cancelled her German citizenship. She remained active in liberal causes and continued to attack Nazism in her writings, most notably with her 1938 book School for Barbarians which was a critique of the Nazi education system.[1]

During World War Two, Mann worked for the BBC, broadcasting in German from London, before becoming a war correspondent attached to the Allied forces advancing across Europe after D-Day. As a correspondent, she attended the Nuremberg trials before moving to America to support her parents who were living in exile there.[1] From the States, Mann continued to write and lecture, often criticising political developments in Europe and American foreign policy. This led to her being investigated by the American authorities who considered deporting her.

After her parents moved to Switzerland in 1952, she also settled there. She wrote a biography of her father and died in Zurich in 1969.[2]

In 1924, Erika Mann began theater studies in Berlin and acted there and in Bremen. In 1925, she played in the premier of her brother Klaus's play Anja und Esther. The play, about a group of four friends who were in love with each other, opened in October 1925 to considerable publicity. In 1924 the actor Gustaf Gründgens had offered to direct the production and play one of the lead male roles, alongside Klaus, with Erika and Pamela Wedekind as the female leads. During the year they worked on the play together, Klaus was engaged to Wedekind and Erika became engaged to Gründgens. Erika and Wedekind were also in a relationship together, as were, for a time, Klaus and Gustaf. For their honeymoon, in July 1926, Erika and Gründgens stayed in a hotel that Erika and Wedekind had used as a couple shortly before, with the latter checking in dressed as a man.[9] Erika's marriage to Gründgens was short lived and they were soon living apart before divorcing in 1929.

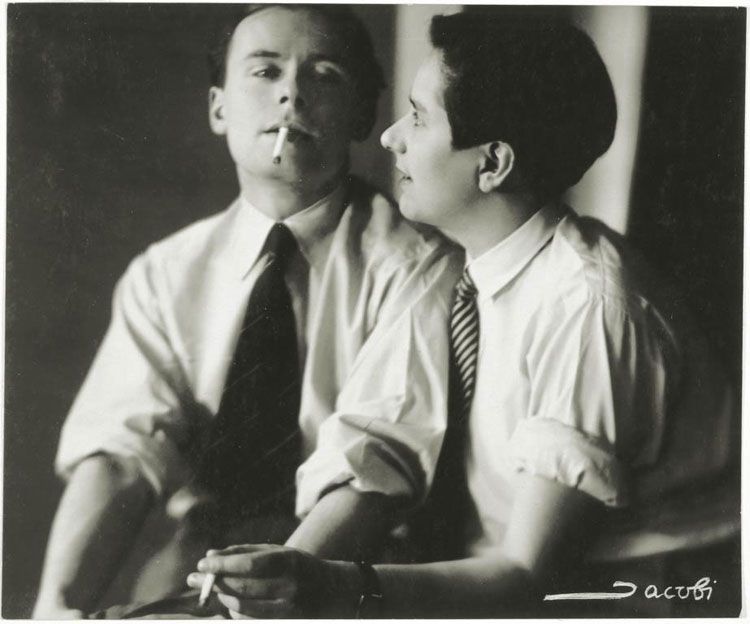

Klaus and Erika Mann by Lotte Jacobi

Erika Mann would later have relationships with Therese Giehse, Annemarie Schwarzenbach and Betty Knox, with whom she served as a war correspondent during World War II.[10]

In 1927, Erika and Klaus undertook a trip around the world,[3] which they documented in their book Rundherum; Das Abenteuer einer Weltreise. The following year, she became active in journalism and politics. She was involved as an actor in the 1931 film about lesbianism Mädchen in Uniform, directed by Leontine Sagan, but left the production before its completion. In 1932 she published Stoffel fliegt übers Meer, the first of seven children's books.

In 1932, Erika Mann was denounced by the Brownshirts after she read a pacifist poem to an anti-war meeting. She was fired from an acting role after the theatre concerned was threatened with a boycott by the Nazis. Mann successfully sued both the theatre and also a Nazi-run newspaper.[11] Also in 1932 Mann had a role, alongside Therese Giehse, in the film Peter Voss, Thief of Millions.

In January 1933, Erika, Klaus and Therese Giehse founded a cabaret in Munich called Die Pfeffermühle, for which Erika wrote most of the material, much of which was anti-Fascist. The cabaret lasted two months before the Nazis forced it to close and Mann left Germany.[11] She was the last member of the Mann family to leave Germany after the Nazi regime was elected. She saved many of Thomas Mann's papers from their Munich home when she escaped to Zurich. In 1936, Die Pfeffermühle opened again in Zurich and became a rallying point for German exiles.

In 1935, it became apparent that the Nazis were intending to strip Mann of her German citizenship;- her uncle, Heinrich Mann, was the first person to be stripped of German citizenship when the Nazis took office.[12] She asked Christopher Isherwood if he would marry her so she could become a British citizen. He declined but suggested she approach the gay poet W.H. Auden, who readily agreed to a marriage of convenience in 1935.[1] Mann and Auden never lived together, but remained on good terms throughout their lives and were still married when Mann died and left him a small bequest in her will.[13][14] In 1936, Auden introduced Therese Giehse, Mann's lover, to the writer John Hampson and they too married so that Giehse could leave Germany.[13] In 1937, Mann moved to New York, where Die Pfeffermühle (as The Peppermill) opened its doors again. There Erika Mann lived with Therese Giehse, her brother Klaus and Annemarie Scharzenbach, amid a large group of artists in exile that included Kurt Weill, Ernst Toller and Sonia Sekula.

In 1938, Mann and Klaus reported on the Spanish Civil War, and her book School for Barbarians, a critique of Nazi Germany's educational system, was published.[1] The following year, they published Escape to Life, a book about famous German exiles.

In 1940, during the autumn height of the Blitz, Stephen Spender published an open letter to Christopher Isherwood in the New Statesman. "You can't escape," wrote Spender. "If you try to do so, you are simply putting the clock back for yourself: using your freedom of movement to enable yourself to live still in pre-Munich England." Isherwood, who left long before the Blitz, was annoyed. So was Dwight Ripley. "It takes in all of us refugees," he complained to Rupert Barneby, while implying that there was more than politics at issue. "I shall always think of the Spenders henceforth as Delight and Inez, How bitter they are, and no wonder." Earlier, Spender in fact urged Isherwood to emigrate to America in search of refuge for his German lover, Heinz Neddermeyer. In Dwight's circle of friends, Brian Howard likewise had a German lover, Toni Altmann. After Hitler was named chancellor, Isherwood spent the next four years, Howard the next seven, each contending with a sucession of revoked visas, expired passports, and sudden deportations in their continuing efforts to find asylum or new citizenship for Neddermeyer and Altmann, respectively, and so prevent their eventual repatriation and arrest in Germany. Both Englishmen tried to get their lovers into England, and both were refused on moral grounds. Erika Mann married W.H. Auden and became a British subject overnight. When Neddermeyer was arrested in Paris, it was Tony Bower who went to rescue him. Isherwood joined them in Luxembourg, but from there Neddermeyer was expelled into Germany, where he was arrested, charged with reciprocal onanism ("in fourteen foreign countries and in the German Reich," remembered Isherwood), found guilty, and sentenced to successive terms in prison, at hard labor, and in the army. Brian Howard's efforts on behalf of Toni Altmann were likewise frustrated at the end. Howard was an early and outspoken antifascist, the first Englishman to understand the Nazi threat, claimed Erika Mann, who, when asked to describe his plans for returning to serve England, had responded in language of persuasive spontaneity: "So, really, I have no plans, except to do my best for Toni." Altmann was interned by the French in Toulon in September 1939, then moved to Le Mans, where Howard lost track of him. Howard remained in France trying to locate his lover until, in June the following year, he escaped on a coal freighter that departed Cannes the day before the Germans arrived in Marseilles.

From America, Mann continued to comment on, and write about, the situation in Germany. She considered it a scandal that Göring had managed to commit suicide and was furious at the slow pace of the denazification process. In particular, Mann objected to what she considered the lenient treatment of cultural figures, such as the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had stayed in Germany throughout the Nazi period.[15] Her views on Russia and on the Berlin Airlift led to her being branded a Communist in America.[11] Both Klaus and Erika came under an FBI investigation into their political views and rumored homosexuality. In 1949, becoming increasingly depressed and disillusioned over postwar-torn Germany, Klaus Mann committed suicide. This event devastated Erika Mann.[10] In 1952, due to the anti-communist red scare and the numerous accusations from the McCarthy Committee, the Mann family left the US and she moved back to Switzerland with her parents. She had begun to help her father with his writing and had become one of his closest confidantes.

After the deaths of her father and her brother Klaus, she became responsible for their works. She died in Zürich suffering with a brain tumour[3] and she is buried at Friedhof Kilchberg in Zürich.[16]

My published books: