Partner Rupert Barneby

Queer Places:

Crelash aka The Spinney, Spinney Lane, Little London, Heathfield, East Sussex TN21 0NU, UK

22 Sussex Pl, Tyburnia, London W2 2TH, UK

Waldorf Towers, 301 Park Ave, New York, NY 10022

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow, Harrow on the Hill HA1 3HP

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

330 N Bristol Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90049

206 W 13th St, New York, NY 10011

The Padre Hotel, 1955 N Cahuenga Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90068

Hotel Carmel - Santa Monica Hotel, 201 Broadway, Santa Monica, CA 90401

9921 Robbins Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

147 S Spalding Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

Wappingers Falls,

Noxon Rd, Lagrangeville, NY 12540

416 E 58th St, New York, NY 10022

Stirling House, 3135 Main Rd, Greenport West, NY 11944

Smith Hill Cemetery,

Honesdale, Wayne County, Pennsylvania, USA

Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley (October 23, 1908 - December 17, 1973) was a noted linguist, plantsman, artist and author. Primarily known as an artist, he was also an important botanist,

poet, philanthropist and polymath who spoke fifteen languages. He was the founding sponsor of the

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which played a crucial role in the development of the New York School and

which set the stage for many vital and important poet/painter collaborations. Ripley and Barneby mixed in literary circles that included

W.H. Auden,

Stephen Spender,

Christopher Isherwood,

Aldous Huxley, the

Sitwells, and

Cyril Connolly. They settled easily therefore into the expatriate community that had formed in Los Angeles around some of these writers in advance of the war.

Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley (October 23, 1908 - December 17, 1973) was a noted linguist, plantsman, artist and author. Primarily known as an artist, he was also an important botanist,

poet, philanthropist and polymath who spoke fifteen languages. He was the founding sponsor of the

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which played a crucial role in the development of the New York School and

which set the stage for many vital and important poet/painter collaborations. Ripley and Barneby mixed in literary circles that included

W.H. Auden,

Stephen Spender,

Christopher Isherwood,

Aldous Huxley, the

Sitwells, and

Cyril Connolly. They settled easily therefore into the expatriate community that had formed in Los Angeles around some of these writers in advance of the war.

"Dwight looked and acted like a handsome international playboy," recalled John Bernard Myers in his memoirs; he also had a "Falstaffian" appetite for drink. Was it true, Douglas Crase later asked Harold Norse, that Dwight was bounced from the Plaza Hotel? "Many times," he responded, laughing. "Dwight the Learned," was the name bestowed by Peggy Guggenheim; "a genius," said Tibor de Nagy. "He's always pinching or patting my ass," reported Clement Greenberg, who in turn once autographed a book for Dwightie, with all my mixed love, Clem. He was "a Gidean nightmare this Dwight," observed Judith Malina; he was "kind & hard & terrible & lovable." In his library you could find W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood, Ronald Firbank and Frederick Rolfe, Baron Corvo, the three Sitwells, the whole privileged cohort of Harold Acton, Evelyn Waugh, Nancy Mitford, Henry Green, and Anthony Powell. Dwight in England had known all but the elder two of these authors.

Dwight Ripley was born in London on October 23, 1908, at his father's London residence of 22 Sussex Place, in the most elaborate of the John Nash terraces (today it is the London Business School ) bordering Regent's Park. His father was a wealthy American, Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley (1864-1913), the grandson of Sidney Dillon, who made a fortune from the Union Pacific Railroad, and his mother a London actress, Alice Louisa Reddy, born in Walworth in 1870, the eldest daughter of John Reddy a tailor. Sidney Dillon (1812-1892) married Hannah Otis Smith (1822–1884); their daughter, Julia E. Dillon married Josiah Dwight Ripley.

When Ripley was only four years old, his father died of the effects of alcoholism, leaving his entire estate to his son, ending any chance of the million dollar trust fund returning to the collaterals. The family seized on a badly written clause in his will to try and deprive the son and his mother of any share of the trust funds. Within a few months of her husband’s death Alice took herself to New York and settled in at the Waldorf Astoria with her son, determined to fight the family trustee’s for her son’s money. Like her deceased husband Alice liked a drink and every evening she would leave her five year old son in the hotel, her jewels stuffed under his mattress to thwart burglars, while she sought out the high life in the bars and nightclubs of Manhattan. At one point in her stay she misplaced her son for three days and was forced to call in the police for help; she had left him in the safekeeping of friends but couldn’t remember which ones. She eventually won her case in the American Courts and Dwight was dubbed by the newspapers The Million Dollar Baby. The pair returned to England where Dwight was rather neglected by his mother who preferred the company of a long line of suitors in London and at the Spinney to that of her son. She died a decade later, in July 1923. She was buried alongside her husband in East Finchley cemetery.

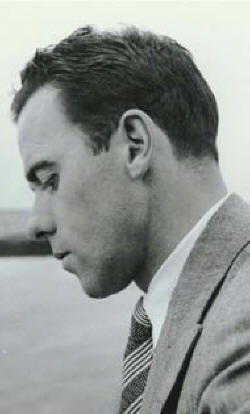

Rupert and Dwight at Harrow

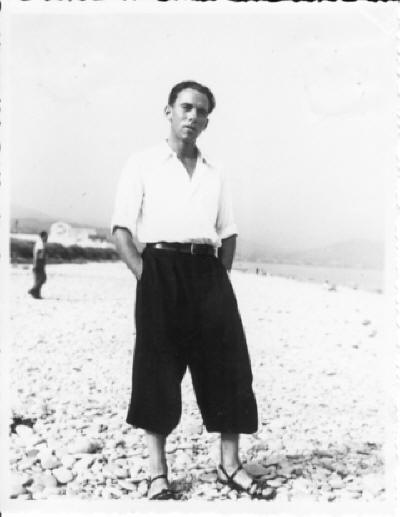

Ripley at Cros de Cagnes, ca. 1931

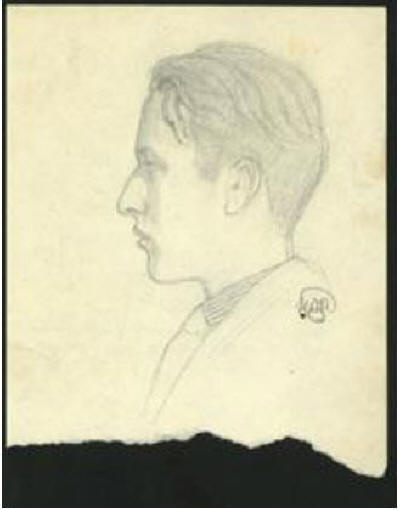

Dwight Ripley. Pencil sketch of Master Rupert Barneby at

Harrow, 1925. In frame.

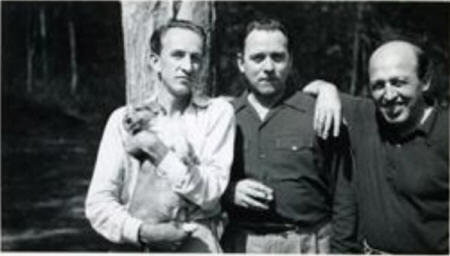

Rupert Barneby (holding Possum), Dwight

Ripley, and Clement Greenberg at Dwight and

Rupert's home at Wappingers Falls, 1951.

Rupert by Dwight Ripley

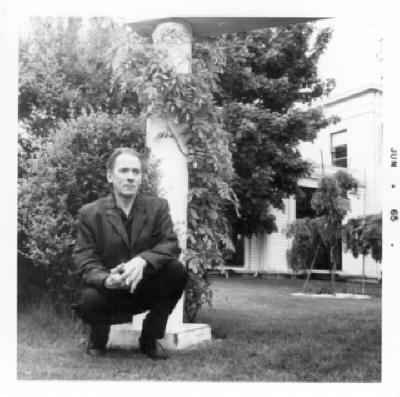

Ripley at Greenport, New York, 1965

Dwight’s boyhood companion at the Spinney was his dog, an Aberdeen terrier called Blackie that was a gift from Rudyard Kipling. The Famous author, a year younger than Dwight’s father, lived once in the United States and had an American wife; his household at Bateman’s, eight miles tot the east of the Spinney near Burwash, was as imperfectly English as the Ripley one.

The orphaned Dwight was sent to Harrow in loco parentis. He began his plant explorations in the 1920s in Northern Africa and Spain with Rupert Barneby whom he met at Harrow where they both attended school. Dwight Ripley, 16, met the younger Rupert Barneby, 14, in 1925 at the British boarding school Harrow. Their friendship scandalized both the headmaster and Rupert's parents. Their boyhood romance became a "lifetime partnership" (as Rupert called it) that lasted 48 years until Dwight's death, at the age of 65, in 1973. After Harrow, Dwight went to Oxford. During Dwight's final year at Oxford, in 1931, the prestigious firm of Elkin Mathews & Marrot published Dwight's collection of 31 poems, called simply Poems, dedicated to "Ruperto Barneby, poetae dilectissumo (the poet's most beloved)." At Oxford, Dwight’s chum was Harold Chown, whose father was French and whose girlfriend, soon to be wife, Hope Manchester, was American. Among Dwight’s chums from the Evelyn Waugh’s generation were Cyril Connolly, distantly Irish and married to an American, Jean Connolly, and Brian Howard, who was raised British but whose parents were American and whose father, moreover, had changed the family name.

Jean Connolly, unfretufully American, was born Jean Bakewell to a wealthy family (Bakewell glass) in Pittsburgh in 1910, arrived in Paris when she was eighteen, and met Cyril Connolly there the next year. On their honeymoon in Mallorca in 1930 the Connollys became friends with Tony Bower. He too was American; his mother was a friend of Dwight Ripley's grandmother in Connecticut, but he had lived in England since he was six, and Dwight knew him from childhood. Bower also attended Oxford, and it was he who introduced Jean to Rupert and Dwight.

Jean Connolly moved in an entourage of young male couples that included Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby, Tony Bower and Cuthbert Worsley, Peter Watson and Denham Fouts, Brian Howard and Toni Altmann. "Drink, night life, tarts and Tonys," complained Cyril Connolly, who referred to the whole entourage as "Pansyhalla." They liked Picasso, Marcel Proust, and Francis Poulenc, favored in architecture the Baroque, admired Josephine Baker and jazz. Someone took a copy of Dwight Ripley's Poems to Jean Cocteau, who responded "Quel néurophate!", a diagnosis that Rupert relayed with wicked relish. When Gerald Heard published two books in 1931 to propose that evolution demanded an evolved human consciousness, Brian Howard called them "the most important that have ever been written since the Ice Age." In Pansyhalla, a compelling example was set by Peter Watson, who joined with Cyril Connolly in 1939 to found Horizon and then financed that influential journal thoughout its career. Until the WWII, Watson lived mostly in Paris; a portrait of Jean Connolly, by Man Ray, was in his apartment. In 1938 he subsized the publication of a first book of poems by Charles Henri Ford, the young poet who was painter Pavel Tchelitchew's lover, and who, back in New York by 1940, would found a counterpart to Horizon, the trendier but likewise influential magazine View. It was View that brought John Bernard Myers from Buffalo to be its managing editor, and Myers who, as director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery that Dwight himself sponsored, acted as impresario for a cast of painters and poets that seems now, to typify the postwar New York scene.

Rupert completed his own curriculum at Cambridge in 1932 and persuaded his father to send him to the university at Grenoble, in France, for further training in languages. He did not explain to his father that Dwight was already there. When Rupert returned to England, Philip Barneby would not meet his son at the Spinney, Dwight's house, not would he allow him home. He summoned him to Hyde Park instead. Relinquish the attachment, he said, and come home as before. Otherwise never return. Rupert never saw his father again.

At the Spinney, Dwight meant to create for Rupert and himself a secure venue for enjoying the avant-garde. Rupert remembered keenly the day in 1932, he was still twenty, Dwight was twenty-three, when they went to the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery, on King Street in London, to buy their first painting. Dwight had picked Parrots in a Cage, painted in 1927 by Christopher Wood, an artist who, long with Paul Nash, is sometimes credited with bringing the flat forms and bold colors of modern European art to English painting.

Dwight Ripley kept a residence in London, and with his partner Rupert Barneby mixed in circles that included Dwight's fellow Oxonians W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, as well as Christopher Isherwood, the Huxleys, the Sitwells, Cyril Connolly and his American wife, Jean Connolly: circles in which the admired standards were for satire in literature and, in society, sarcasm and wit. Jean Connolly, who became one of Dwight's closer friends, was at the center of avant-garde sets on both sides of the Atlantic; she was the only woman, said Auden, who could keep him up all night. At a party in 1935 at Richard Wyndham's house, the Tickerage (Wyndham was a soldier, writer, and photographer who was killed covering the Arab-Israeli was in 1948), the guests were Dwight Ripley and Jean Connolly, Patrick Balfour (later Lord Kinross), Constant Lambert (the composer), Angela Culme-Seymour (who was to marry Balfour), Tom Driberg (the columnist "William Hickey" at the Daily Express and later member of Parliament), Cyril Connolly, Stephen Spender, Tony Hyndman (Spender's boyfriend), Mamaine Paget (later the second wife of Arthur Koestler), John Rayner (also of the Daily Express), and Joan Eyres-Monsell (later Leigh-Fermor).

When the impending civil war made it impossible to collect in their beloved Spain, Rupert and Dwight decided on a substitute destination where the language was also Spanish and the condistions semiarid: Mexico. They arrived in 1936 in Los Angeles and readied themselves for an expedition south.

In 1938 they were back in California. This time the live plants they collected were established temporarily in a holding garden at 330 North Bristol, the imposing Spanish-style residence they rented in the Brentwood setion of Los Angeles. From 330 they mounted expeditions eastward to Death Valley and Titus Canyon, hoping to find the unusual, yellow-flowered Maurandya petrophila.

Barneby, who had been disinherited, and Ripley, whose personal fortune always paid the bills, headed straight to Hollywood, where they were quickly disillusioned by seeing Clark Gable without pads on his shoulders and torso. ''He was a little shrimp of a man,'' Barneby lamented.

W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood had left England in January 1939. Auden stayed in New York, but Isherwood went on to Los Angeles, where he joined Dwight's still closer friends, Christopher Wood and Gerald Heard, who had emigrated along with Aldous Huxley, Maria Nys, and son Matthew Huxley two years before. Rupert obtained a new passport in June, and by October 1939 the two men were in New York.

Rupert went immediately west, meanwhile Dwight had rented an apartment at 206 West 13th Street, in Greenwich Village, and set out to master the customs of the country. "I'm setting my, er, cap at one of the waiters in the Troc, but no progress so far," he complained. "They're all venal in that joint, from the manager downward, but the approach is so difficult in God's country. I long to say just $20, but that's impossible for some extraordinary reason." One had to pretend, he continued in exasperation, to be "doing it all for "love", My God, Americans don't know what that word means..."

They collected plants to grow at the Spinney, Ripley’s home in Sussex, as well as specimens for herbaria. The 1,138 species in their garden are identified in A List of Plants Cultivated or Native at the Spinney, Waldron, Sussex (1939). In 1939, the two men moved to California and traveled extensively in Mexico and the western United States, again collecting plants for their garden and for herbaria. Ripley wrote numerous articles about these collecting trips that were originally published in the Quarterly Bulletin of the Alpine Garden Society (U.K.). Excerpts are reprinted in Impressions of Nevada: the countryside and some of the plants as seen through the eyes of an Englishman, an occasional paper of the Northern Nevada Native Plant Society (1978).

In late 1939, Rupert Barneby and Dwight Ripley lived at Padre Hotel, Hollywood, and they became part of the wartime colony of English expatriates that soon flourished along the southern California coast. At the beginning of WWII, Jean Connolly moved to Los Angeles and brought her close friend, Denham Fouts, a storied young American who was the lover then of Peter Watson, the wealthy publisher of Horizon, and was widely assumed to have been, before that, the lover of Prince Paul of Greece. These are the figures satirized by Christopher Isherwood in his novel Down There on a Visit, a novel in which the portrayal of Jean Connolly as Ruthie is so rude that it confirmed, said Rupert Barneby, Dwight Ripley's longstanding opinion that Isherwood was a snit. Soon the circle of expatriate friends around Dwight and Rupert had expanded to include several who found work, as did Isherwood, in the motion-picture industry. Especially close to Dwight were Keith Winter, a novelist, playwright, and Oxford classmate who worked as a screenwriter on Joan Crawford movies (he wrote the screenplay for Above Suspicion), and Richard Kitchin, a set artist who painted a Surrealist portrait of Dwight.

Early in WWII, Peter Watson had arranged a studio for the Scottish painters Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde (they were known as "the two Roberts" because they were a couple.) Later he provided support to John Craxton, Michael Wishart, and Lucian Freud. Dwight Ripley joined in this project, if marginally, when he bought an oil by MacBryde and lent it to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

In 1940, during the autumn height of the Blitz, Stephen Spender published an open letter to Christopher Isherwood in the New Statesman. "You can't escape," wrote Spender. "If you try to do so, you are simply putting the clock back for yourself: using your freedom of movement to enable yourself to live still in pre-Munich England." Isherwood, who left long before the Blitz, was annoyed. So was Dwight Ripley. "It takes in all of us refugees," he complained to Rupert Barneby, while implying that there was more than politics at issue. "I shall always think of the Spenders henceforth as Delight and Inez, How bitter they are, and no wonder." Earlier, Spender in fact urged Isherwood to emigrate to America in search of refuge for his German lover, Heinz Neddermeyer. In Dwight's circle of friends, Brian Howard likewise had a German lover, Toni Altmann. After Hitler was named chancellor, Isherwood spent the next four years, Howard the next seven, each contending with a sucession of revoked visas, expired passports, and sudden deportations in their continuing efforts to find asylum or new citizenship for Neddermeyer and Altmann, respectively, and so prevent their eventual repatriation and arrest in Germany. Both Englishmen tried to get their lovers into England, and both were refused on moral grounds. Erika Mann married W.H. Auden and became a British subject overnight. When Neddermeyer was arrested in Paris, it was Tony Bower who went to rescue him. Isherwood joined them in Luxembourg, but from there Neddermeyer was expelled into Germany, where he was arrested, charged with reciprocal onanism ("in fourteen foreign countries and in the German Reich," remembered Isherwood), found guilty, and sentenced to successive terms in prison, at hard labor, and in the army. Brian Howard's efforts on behalf of Toni Altmann were likewise frustrated at the end. Howard was an early and outspoken antifascist, the first Englishman to understand the Nazi threat, claimed Erika Mann, who, when asked to describe his plans for returning to serve England, had responded in language of persuasive spontaneity: "So, really, I have no plans, except to do my best for Toni." Altmann was interned by the French in Toulon in September 1939, then moved to Le Mans, where Howard lost track of him. Howard remained in France trying to locate his lover until, in June the following year, he escaped on a coal freighter that departed Cannes the day before the Germans arrived in Marseilles.

In December 1941 Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby moved from the Santa Monica Hotel to a more satisfactorily residential address, 9921 Robbins Drive in Beverly Hills, and invited to dinner Miss Dicky Bonaparte, an immigration counselor was was skilled at getting alien actors and actresses into the country, and who had arranged earlier a legal arrival for Christopher Isherwood. This is how they obtained a legal entry in the United States for Barneby.

Early in 1942, Barneby and Ripley went to New York, joining their friend Jean Connolly, who had moved east and could introduce them immediately to the art world that Rupert like to call "Upper Bohemia." Jean's current lover, only somewhat to the chagrin of her likewise active husband back in England, was Clement Greenberg, the critic who would help make Jackson Pollock famous. Greenberg, writing to his friend Harold Lazarus described the new arrivals: "Dwight Ripley, a millionaire and rather masculine... and his pal, Rupert Barneby. They are both botanist and English," reported Greenberg, "and Dwight is in addition a philologist, expert in the Latin languages and Russian. Something new." In August the two men took a one-year lease at 147 South Spalding Drive in Beverly Hills. Bu the time the lease was ready to expire, they had bought an old farmhouse and its surrounding hundred acres on Noxon Road in the town of LaGrange, Dutchess County, New York. This was 20 miles from Jean Connolly's house in neighboring Connecticut. Dwight arrived first, July 24, 1943. On a shape outcrop behind the farmhouse they started a rock garden.

Ripley and Barneby moved to New York in 1943 and they did not return to Sussex. Their plant collection at the Spinney was auctioned in 1951 with most of the rarities going to botanic gardens at Cambridge and Kew.

Jean Connolly by this time had dropped Greenberg and was involved with Laurence Vail, the Surrealist artist and former husband of Peggy Guggenheim, heiress, angel of expatriate European artists, and owner of Art of This Century Gallery. With bohemian aplomb, however, it was the two women who began living together in Guggenheim's duplex at East 61st Street, New York. Thank to this arrangement, Rupert and Dwight found themselves frequently in New York at the center of Upper Bohemia. "Jean Connolly, Dwight Ripley, Matta, Marcel Duchamp were around a great deal," recalled Lee Krasner, the painter who was Jackson Pollock's wife. "They were at all the parties." Rupert and Dwight were at the now famous party during which Pollock's Mural was first shown and Pollock relieved himself in the fireplace. Barneby remembered Marcel Duchamp, the avatar of cool in the art world today, as a "pompous pundit." He recalled Guggenheim herself as "mean"; she "dressed like a hag," her stagy consersational asides were "like a dagger in the heart."

A respected artist, Ripley exhibited his drawings at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery in New York. He was the major financial contributor to the establishment of the Tibor de Nagy Art Gallery of John Bernard Myers and had five one-man shows there. Ripley and Barneby built two large rock gardens at their homes in New York, first at Wappingers Falls, Dutchess County and subsequently in Greenport, Long Island.

In 1943, Dwight and Rupert purchased an old farmhouse with a hundred acres in the Town of LaGrange, Dutchess County, New York. It was twenty miles from Jean Connolly's home in Connecticut. They simply called it "the Falls" after its nearby postal address of Wappingers Falls. Wappingers Falls was a large property of a hundred and five acres. A simple farmhouse had been adapted into a comfortable rural retreat with a rock garden, lawns and a fine greenhouse surrounded by beautiful woods. Both Ripley and Barneby were serious scientists: the rockery and greenhouse contained a wide variety of specimens from various parts of the world, copperstriped miniature tulips from behind the casino of Monte Carlo; a tiny lilac from Siberia sent by their fellow botanist Justice William O. Douglas; small, exquisite iris from Turkey. The greenhouse featured conical-shaped flycatchers, as well as tables of seedlings and cuttings. Ripley was an accomplished linguist and both spoke and wrote a dozen languages, including one as archaic as Catalan. He surprised Mirò when he sent the artist some verses in the master's native tongue. "How could anyone write such poetry who wasn't a Catalonian?" Mirò wrote back, delighted of course with Ripley's homage. Inside the house there was a wonderful library containing everything from novels, poetry and travel books to a superb collection of botanical volumes, as well as a host of dictionaries, atlases, encyclopedias. Also artworks, many Miròs, several Joseph Cornell boxes, a wide variety of abstract paintings, some fine XIX century prints and watercolors, Edward Lear landscapes and a collection of XIX century, highly fanciful birdcages. They could not abide any servants in the house. They compromised with a groundsman to help with the outside gardens and woods. Barneby was a skillfull cook; his meals were no-nonsense elegant, simple but delicious.

In 1945 Willard Maas published a poetry anthology, The War Poets. The love sonnet Letter to R, written by Maas while an army private at Camp Crowder, MO, was intended for Rupert Barneby. Maas was to become an influential avant-garde filmmaker after the war, and Dwight Ripley would help finance his projects. For his part, Dwight soon was having an affair with Peggy Guggenheim, who admired his English accent, his youth (he was ten years younger), and his indifference to her wealth. She liked to introduce him as her fiancé. "She fell abruptly out of love with Dwight," said Rupert. "On December 14, 1945, he was staying at her house at East 61st and she'd gone out to some party, and Dwight came back in a cab with a very handsome driver, Henry Lessner, and Peggy found them in bed together." The next morning Dwight was a registered guest at the Prince George Hotel. On Sunday he attended a party at Guggenheim's apartment, on Tuesday he sent her caviar, and on Wednesday he went home to Wappingers Falls. His infraction, he claimed later, was not getting in bed with a man, it was getting caught in bed with a chauffeur.

At Harrow, Dwight already liked to draw, and in the US he began to draw with the same kind of attention he gave to languages and botany. His work was done almost entirely in colored pencil on paper, at a time that made him a pioneer in this medium, and his first showing was arranged by Peggy Guggenheim, the year after the cabdriver incident, at Art of This Century.

Harold Norse was Dwight Ripley's obsession of the 1951 season, and Norse was richly rewarded by him with the gift of an expensive Picasso that made it possible for him to move to Italy. Fidelity was not a Norse characteristic; as Rupert Barnaby, later said, "Dwight is not a griever or a whiner. Gone are the snows of yesterdays." Norse portraied Dwight in his memoirs as the millionnaire "Cyril Reed". Norse had an apartment at 573 Third Avenue, where he lived one floor above a New Zealand painter, Glyn Collins (for a short time in 1945 the husband of Muriel Rukeyser), who was commissioned by Dwight Ripley to paint a portrait of Tony Bower. When Collins gave a party he invited his upstairs neighbor Norse. Other guests that evening included the painter-and-poet couple Theodoros Stamos and Robert Price; the Abstract Expressionist painter William Baziotes and his wife, Ethel; the Living Theatre's founders-to-be Julian Beck and Judith Malina; the social philosopher Paul Goodman and his wife, Sally; John Bernard Myers and his roommate, Waldemar Hansen; the poet Ruthven Todd; and Dwight and Rupert. Dwight, reports Norse in his memoirs, was drunk, fell for him with a "thud heard round the room," and before passing out inquired what he most wanted. Norse had no way of knowing that Dwight a decade earlier had complained, "I long to say just $20." No doubt he did know, by way of Chester Kallman and W. H. Auden, the story of Denham Fouts and the liquidated Picasso given to him by Peter Watson. "Taking it as a big joke," writes Norse, "I blurted out with drunken laughter, "How about a Picasso?" "Is that all?" he screamed. "Daahling, it's yours!" A few days after the party a limousine arrived on Third Avenue, and the surprised Norse opened his door to find a chauffeur, in uniform, who had come to deliver a 1923 Picasso gouache, a ten-by-sixteen-inch study for The Dancers, certified by Pierre Matisse. In his memoirs, Norse gives a vivid account of the ensuing affair (dinners at Le Pavillon and Chambord, trips to the galleries, visits to the New York Public Library, where Dwight read War and Peace in Arabic), and he reveals also that his new admirer never touched him. He credits the forbearance to his own virtue and not to Dwight's. It all came to an end on a winter evening outside the Chelsea Hotel. "He had told me earlier," recalled Norse, "because he was a masochist, if you ever want to get rid of me, and you'll never see me again, just say "I love you" and you'll never see me again. So outside this hotel he said, "Harold, do you love me?" and I said, "Yeah," and I never saw him again." The previous autumn, Ripley recorded in his diary that Norse and Norse's lover during the whole affair, Dick Stryker, were going to Wappingers Falls, Ripley's country house in Upstate New York, to spend the weekend. He made a not to get his drawings down from upstairs. Fifty years later, when Douglas Crase, Ripley's biographer, asked Norse by telephone what he thought of Dwight's drawings, he replied, "I never knew Dwight could draw or would even bother to do something artistic. Dwight an artist, no, I had no idea. I can't believe it."

Always in 1951 Dwight Ripley offered to back the Tibor de Nagy Gallery opened by John Bernard Myers as gallery director. Dwight missed the excitement generated by Peggy Guggenheim's art gallery, closed in 1947 when she followed the last of the exiled Surrealist back to Europe. In London, his Oxford contemporary Peter Watson had helped found the Institute of Contemporary Arts and was planning shows to feature the painters Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Encouraged, probably goaded by this example, Dwight turned to his art-critic friend Clement Greenberg for help. On the Monday evening of January 23, 1950, he took aspiring art dealer John Bernard Myers to Greenberg's apartment in Greenwich Village. "Ripley and John Myers," confirmed Greenberg's biographer 47 years later, "came to Clem's apartment to consult with him about a noncommercial gallery that Ripley would finance as silent backer and Myers would run." Greenberg suggested the initial artists, Dwight wrote the first check, and the result was Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which opened its doors that December and rapidly became one of the influential art galleries in New York. In its first full year Dwight provided the gallery with more than 5.000$, or five time its annual rent. This was an historic contribution. Tibor de Nagy sponsored the first solo shows of Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Fairfield Porter, artists whose works would alter the conventions, then supreme, of Abstract Expressionism. When the gallery's director John Myers published the first chapbooks of poets John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, and Kenneth Koch, Dwight's support altered the conventions of poetry as well.

Rupert Barneby owned a copy of Frank O'Hara's Oranges, its cover individually painted by Grace Hartigan, who in those days signed herself George. It was inscribed "to darling Dwight and Rupert, oranges and kisses, George."

Dwight had begun more seriously to draw. In the 12 years from 1951 through 1962 he had five solo shows at Tibor de Nagy. During its first full year of operation, in 1951, the Tibor de Nagy Gallery sold more work by Dwight Ripley than by any other artist. The list of collectors who owned Dwight's work could be read as a network of friends or as a sign of shared tastes within an avant-garde; included were Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, John Latouche, Betty Parsons, Peggy Guggenheim, Alfonso Ossorio, Joe LeSueur, Marie Menken, and Willard Maas.

The decision to remain in the United States had become inevitable, and by November 1951, when W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood arrived to spend a nostalgic weekend with Rupert and Dwight at Wappingers Falls, it was irrevocable too. England, for all four, was the place they had left behind. The rare species cultivated at the Spinney, Waldron, Sussex, were auctioned earlier that spring. The Spinney itself passed to a new owner, the solicitor who all these years had managed Dwight's interests under the terms of his father's will.

In 1957 the experimental filmmaker Marie Menken was so fascinated with the rock garden at Wappingers Falls, that she filmed a five-minute, 16mm film, Glimpse of the Garden, described by Stan Brakhage as "one of the toughest" of her influential works. Menken was the wife of Willard Maas, the soldier poet once enamored of Rupert. In 1959 Menken directed an animated, three-and-one-half-minute, 16mm film with the peculiar title of Dwightiana. The film was made from stop-motion sequences that Menken filmed in Rupert and Dwight's apartment at 416 East 58th Street in New York.

For a few years beginning in 1957 the two men rented an apartment at 416 East 58th Street, near Sutton Place, in New York. The young Gore Vidal collected the rent. In the city, Dwight seemed only to drink more heavily. When he tried simply to stop, the effects of the withdrawal landed him in Vassar Hospital. Shaken, he resolved on sobriety, and together he and Rupert decided to move to a house they had found for sale in Greenport, Long Island, not far from their painter friends Theodoros Stamos, Lee Krasner, and Alfonso Ossorio. They arrived in October 1959, eager to renovate the decaying Greek Revival mansion that stood at 3135 North Road on the east edge of town. To Tom Howell, Dwight wrote that he was "now happily esconced in a divine house which, along with its new owner, has been saved in the nick of time from Crumbling into Ruins."

People in Dwight Ripley's private audience were artist friends from the east end of Long Island who comprised, with Tony Bower, a remainder of the old Upper Bohemia: Lee Krasner in Springs, Alfonso Ossorio and dancer Ted Dragon at their estate, the Creeks, in East Hampton, and Theodoros Stamos, who, with his younger lover Ralph Humphrey, lived nearby in a house he had built in East Marion. Stamos and Humphrey sometimes brought Mark Rothko; when Frank Polach and Douglas Crase asked for a comment on these historic visits, Rupert Barneby's response was "They didn't know how to sit in a chair!" Humphrey had a show of all-black paintings at Tibor de Nagy in 1959, and his subsequent shows at that gallery were likewise in close-valued monotones. Stamos responded to Humphrey's example by restricting the color range in his own work. The red-versus-white standoff of Ahab for R.J.H., now in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, was painted in homage to Humphrey.

As Ripley's assets steadily diminished, the couple lived off sales from their painting collection. Miro's Constellation No.5, now at the Cleveland Museum of Art, provided the funds for their first collecting trip to Mexico in 1963.

Ripley's extensive manuscript held in the archives of the NYBG, the Etymological Dictionary of Vernacular Plant Names, was nearing completion at the time of Ripley’s death on December 17, 1973. The year after his death, Barneby paid tribute to their collecting life together by arranging for the editor and gallerist John Bernard Myers to publish Ripley's botanical journals in his obscure but influential art journal Parenthèse. In 1974, Ripley and Barneby were honored with the American Rock Garden Society’s Marcel Le Piniec Award for their plant explorations and introduction of new rock garden species. Index Kewensis lists six species named after Ripley: Cymopterus ripleyi, Aliciella ripleyi, Astragalus ripleyi, Eriogonum ripleyi, Omphalodes ripleyana and Senna ripleyi, the first three of which he co-discovered with Rupert Barneby. Ripley, a cousin of the long-time Smithsonian director, S. Dillon Ripley, was fluent in more than 15 languages and dialects.

The Douglas Crase / Frank Polach & Rupert Barneby / Dwight Ripley Archives are interconnected archives representing the lives of four individual and remarkable men. The archives offer multiple access points into the exploration of the New York School of poets and painters, (especially its connection with the Tibor de Nagy Gallery) and aspects of the New York avant-garde (including Marie Menken, Willard Mass, Peggy Guggenheim, Clement Greenberg, Alfred Leslie, Jane Freilicher, Helen Frankenthaler, Judith Malina, John Bernard Myers, and others); the worlds of botany and gardening through two generations; and gay culture and life from 1925 on.

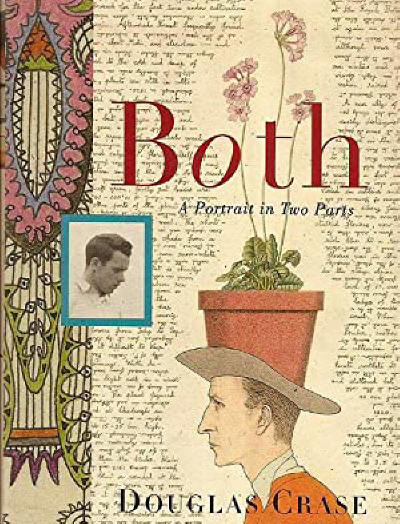

Frank Polach first met Rupert Barneby in 1975 at The New York Botanical Garden. The two shared an interest not only in botany, but also art and poetry. Both Douglas Crase and Frank soon became close friends with Rupert. In 1998, Douglas and Frank helped move Rupert from his New York Botanical Garden loft into an assisted living home. They shipped many of Rupert and his late partner Dwight Ripley's items to their Carley Brook home in Pennsylvania. Crase began reading Ripley's diaries and found that they illuminated Ripley's extensive role in the postwar art world and his part in the creation of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Rupert Barneby died in 2000 and left many of his belongings to Frank, who was also the executor of his estate. In 2004, Douglas published Both: A Portrait in Two Parts, a dual biography of botanist Rupert Barneby and artist Dwight Ripley, that incorporated much of the material that had been willed to Frank Polach.

Eleanor D. Acheson (born 1947), Harry Dwight Ripley (1908-1973) and Rt. Rev. Mary Glasspool (born 1954), all descend from the same Mayflower Pilgrims, William White, Susannah Jackson and Edward Winslow.

Tony Scupham-Bilton -

Mayflower 400 Queer Bloodlines

My published books: