Queer Places:

Newcomb College, Newcomb Cir, New Orleans, LA 70118

Pontalba Buildings, 500 St Ann St, New Orleans, LA 70116

Greenwood Cemetery

New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, USA

Louis

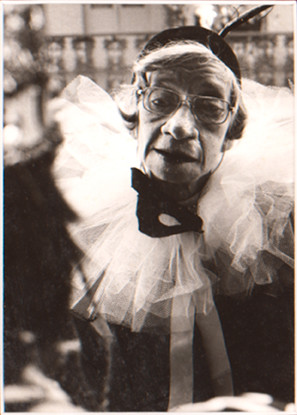

Andrews Fischer (1901 - August 17, 1974) was a gender-bending Mardi Gras designer, named

for her father.

Louis

Andrews Fischer (1901 - August 17, 1974) was a gender-bending Mardi Gras designer, named

for her father.

When Louis Andrews was born in 1901 she was given the first name of her father, a Mobile ship broker. Louis Sr. left the family when his daughter was five years old, and his wife moved with the young Louis and her younger sister to New Orleans. As a child, Louis read avidly, especially poetry and fantasy—Alice in Wonderland was a particular favorite—and at sixteen she entered Newcomb College, where she became widely known for her coruscating wit. Impressed by her artistic talent, Ellsworth Woodward steered her toward Mardi Gras design. Carnival historian Henri Schindler reports that by 1926 she had designed “parades and costumes for Rex, Momus, and Proteus, and invitations for Comus and The Mystic Club.” (Happily, the theme for the Momus parade in 1923 was “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”)

Schindler notes that the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Deco, and the Ballets Russes all influenced Louis’s designs, but adds that “none of them shaped her style more than her lifelong loves, literature and nonsense.” For instance, gender-bending was rarer in New Orleans a century ago than it is now, and Louis was a pioneer. The influence of her masculine name (which always caused confusion: newspapers referred to her as Lois, Louise, and Mrs. Louis Andrews) was augmented by her mother’s tendency to dress the child in boyish clothes, a pattern that Louis continued on her own at Newcomb, where, according to Schindler, she was “usually attired in tweed jackets and neckties” (although, to be sure, she “also made dramatic appearances on campus in the costumes of various nationalities”). As a Carnival designer, she “relished the genial mischief and occasionally sublime comedy” of costuming prominent New Orleans businessmen as “Southern belles in hoop skirts, pioneer women in gingham and bonnets, queens Elizabeth, Antoinette, and Victoria,” and the like. The 1924 Rex parade alone included gentlemen representing Salome, Jezebel, Joan of Arc, and Lucrezia Borgia.

Louis did not confine her work to Mardi Gras events. In one 1925 issue of the Times-Picayune, for instance, she illustrated a children’s story called “Hiawatha’s First Great Battle” (“As Retold by Lydia Sehorn”—Mrs. Roark Bradford), and Lyle Saxon reported that “in the Quarter these days, one hears much of the work of Miss Louis Andrews, delightful line drawings of vividness and charm,” calling particular attention to some recently published in the New York Times. The next year, the Morning Tribune illustrated a story about the Arts and Crafts Club with her sketch of the courtyard at its Royal Street headquarters. Louis lived with her mother and sister in the Pontalba apartments, where her neighbors and good friends included Ronald Hargrave, Cicero Odiorne, and Harold Levy. Bill Spratling was another friend (Flo Field said that Louis and Spratling had pet names for each other, but didn’t reveal what they were).

Louis made occasional appearances in the society pages—a newspaper story reported that “stunts” for the Arts and Crafts Club’s 1925 Bal des Artistes would be under her “personal direction,” and another article reported that she was present at an “impromptu studio party” in the Quarter and “did her part to make [it] a grand success”—but her social life really picked up after she married Lawrence Fischer in 1926. Louis and her husband (whose occupation was reported in the 1930 census as “manager/florist”) moved to the lower Pontalba building, had a baby boy, and played frequent hosts to informal Sunday afternoon gatherings of the artistic set. Their apartment was also the scene of grander parties like one held to honor a (fictitious) young artist named Narkiss Nietzke, at which the hired policeman on the door turned away a good many prominent citizens who had been sent forged invitations by some practical joker.

The stock market crash put a crimp in the celebration of Mardi Gras. Louis’s last Rex parade was in 1930. The Fischers opened a bookshop on St. Peter Street that became a popular meeting place for their crowd. Louis started working at Le Petit Theatre and spoke at the Arts and Crafts Club on “Stage Craft and Design.” Although she kept her hand in, doing Mardi Gras costumes and settings for balls, she designed no parades until 1964. In that year, however, she returned to float design, staging a successful second act in a remarkable only-in-New Orleans career that continued until her death in 1974.

In 1926 Pelican Bookshop Press, New Orleans, published "William Spratling and William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles: A Gallery of Contemporary New Orleans", issued in 250 copies. The “Famous Creoles” (with ages in 1926) were

My published books: