BURIED TOGETHER

Queer Places:

612 Royal St, New Orleans, LA 70130

534 Madison St, New Orleans, LA 70116

Shadows-on-the-Teche, 317 E Main St, New Iberia, LA 70560

3 Christopher St, New York, NY 10014

Magnolia Cemetery

Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, USA

Lyle

Chambers Saxon (September 4, 1891 – April 9, 1946) was a respected New Orleans writer and journalist

who reported for The Times-Picayune. It has been suggested that his only great love was his childhood friend,

George Favrot, who died young

in 1925. Other sources maintain that he had a sexual relationship with Joe Gilmore, his long-time black valet. Biographer James W. Thomas interviewed many of Saxon's closest friends and concluded, "Saxon'shomosexual affairs were discreet, never a problem for his heterosexual friends, and not a significant partof his literary life."

Saxon’s biographer Chance Harvey says that Thomas C. Atkinson of Baton Rouge

told her that Saxon and his friend George Favrot were caught “in drag” and

expelled from school, but that Atkinson offered no corroboration.

Lyle

Chambers Saxon (September 4, 1891 – April 9, 1946) was a respected New Orleans writer and journalist

who reported for The Times-Picayune. It has been suggested that his only great love was his childhood friend,

George Favrot, who died young

in 1925. Other sources maintain that he had a sexual relationship with Joe Gilmore, his long-time black valet. Biographer James W. Thomas interviewed many of Saxon's closest friends and concluded, "Saxon'shomosexual affairs were discreet, never a problem for his heterosexual friends, and not a significant partof his literary life."

Saxon’s biographer Chance Harvey says that Thomas C. Atkinson of Baton Rouge

told her that Saxon and his friend George Favrot were caught “in drag” and

expelled from school, but that Atkinson offered no corroboration.

Once, when interviewed, Richmond Barthé indicated that he was homosexual. Throughout his life, he had occasional romantic relationships that were short-lived.[37] In an undated letter to Alain Locke, he indicated that he desired a long-term relationship with a "Negro friend and a lover". The book Barthé: A Life in Sculpture by Margaret Rose Vandryes links Barthé to writer

Lyle Saxon, to African American art critic

Alain Locke, young sculptor

John Rhoden, and the photographer

Carl Van Vechten. According to a letter from Alain Locke to

Richard Bruce Nugent, Barthé had a romantic relationship with Nugent, a cast member from the production of Porgy & Bess.[38]

Homosexual characters or subjects do not appear anywhere in his published work. Saxon is his most unguarded in letters he exchanged with his friend artist

Weeks Hall, master of Shadows on the Teche, his ancestral family home on Bayou Teche in southwestern Louisiana. Saxon was havingcharacteristic fun as he privately wrote, "As for the miasmas rising from the Teche, I cannot bring myself tothink that the effluvia does aught stir indiscreet thoughts, and, alas, perhaps, indiscreet actions as well. Iremember in my own case, on certain summer evenings . . . but why speak of our gaudy youth, dear Coz, aswe approach Life's Sunset?"

Saxon was born on September 4, 1891, either in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, or

in New Whatcom, Washington, now incorporated into Bellingham, Washington,

while his mother, Katherine Chambers, was traveling away from home; the early

history of his life is "as evasive as the histories that frustrated Saxon in

writing Old Louisiana".[1]

The confusion is based on Saxon's alleging he was born in Baton Rouge, but his

birth certificate states New Whatcom, Washington.

[2]

It is possible that his parents, from distinguished families with connections

to Baton Rouge and New Orleans, were unmarried, although the birth certificate

lists the birth as "legitimate"; Saxon said little about his background and

early years, and never met his father, Hugh Saxon.[1]

He was raised, however, in Baton Rouge, and made frequent trips to New Orleans

throughout his early life, where his paternal uncle and grandmother lived.[3]

His grandmother, Elizabeth Lyle Saxon, was a poet, author, and prominentearly suffragette. In addition, his maternal grandfather, Michael Chambers, owned the first bookstore inBaton Rouge, Louisiana, long an institution in the town.

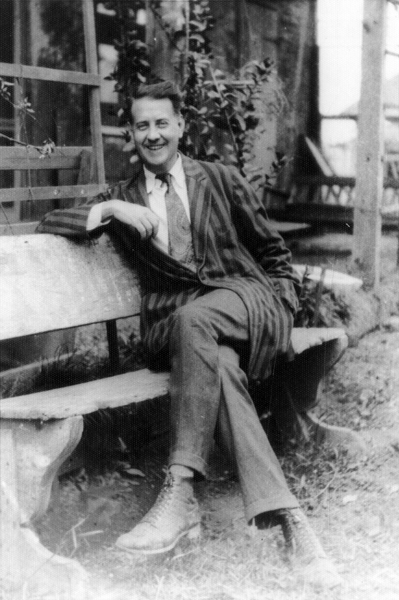

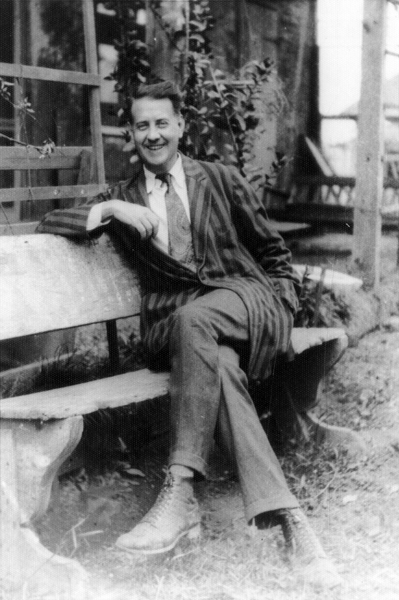

Lyle Saxon and Henry Tyler

by Joseph Woodson “Pops” Whitesell

Shadows-on-the-Teche

Saxon moved to New Orleans not long after college in 1914 or 1915 and,

after moving again several times, settled there permanently in 1918.[4]

Saxon was an early and avid preservationist. He lived in the Quarter from his

first days in New Orleans, when he roamed its streets with his fellow

journalist Flo Field and his boyhood friend George Favrot, despite the

warnings of friends that those streets were not just seedy but dangerous.

(They were right: Saxon claimed that he was once bound and tortured by three

burglars who didn’t believe he had no valuables.) Soon Alberta Kinsey and a

few other urban pioneers joined him. After renting a couple of places on Royal

Street he was finally able to buy one, and moved his collection of period

furniture there in 1920.

Saxon lived in the French Quarter at 612 Royal St. starting in 1918. He personally restored two importantbuildings himself and led the city's preservationist movement. Soon Saxon began to attract a brilliant assortment of young writers and artists. Traipsing in and out of hissalon on Royal Street, and swigging contraband Prohibition liquor, were

Tennessee Williams, William Faulker, William Spratling,

Sherwood

Anderson and Elizabeth Anderson,

Edmund Wilson, Dorothy Dix,

John Dos Passos, and John Steinbeck.

William Spratling wrote that

he and his French Quarter friends “saw each other every day, almost every

evening. If it wasn’t at Lyle Saxon’s house, it was at Sherwood and

Elizabeth’s or my own.” People just dropped in. According to Mrs. Anderson,

“No one was ever invited, for that would make it seem as though they had to be

invited before they would be welcome.” Almost every Saturday night the

Andersons had a dinner party for a rotating group of friends and visitors to

New Orleans. Spratling remembered that the guests might include “John Dos

Passos, or perhaps Carl Sandburg or Carl Van Doren or a great publisher from

New York, Horace Liveright or Ben Huebsch, all people we were proud to know.”

Olive Boullemet Lyons

Olive Boullemet Lyons was the

elegant, cultivated, Creole wife of a wealthy cotton broker whose family owned

a pharmaceutical business. Edmund Wilson told his friends back in New York

that she was “the most charming woman in the South,” and put an admiring

sketch of her in his book, The Twenties. She kept one of the city’s most

beautiful gardens, furnished her house with exquisite taste, and was an

accomplished cook. She also smoked and drank heavily, bobbed her hair, drove a

Stutz Bearcat, published poetry, and worked on the Double Dealer. Sherwood

Anderson thought she looked “like a Russian prostitute,” and gossip linked her

romantically to Lyle Saxon (although he was gay). A portrait by

Charles Bein shows her in a

gold gown and tiara.

Saxon was an ardent student of the history of New Orleans and wrote six books

on the subject. His most popular titles include "Fabulous New Orleans"

recounting the city's celebrated past as set against his memories of his first

Mardi Gras during the turn of the 20th century: "Gumbo Ya-Ya", an amazing and

absolutely marvelous compilation of native folk stories from Louisiana,

including the Loup Garou and the Lalaurie House: and "Old Louisiana", a local

bestseller from its introduction in 1929.

He was always a great admirer of Grace

King: he dedicated his book Fabulous New Orleans to her, and served as

pallbearer and eulogist at her funeral. It was at one of Miss King’s Friday

afternoon salons that he met

Cammie Henry, the

mistress of Melrose Plantation, near Natchitoches, who was in the process of

turning her place into a retreat for writers and artists. By 1926 Saxon was

spending many weekends and the odd month at Melrose, a 250-mile journey each

way. He said he found it easier to write there, but one suspects the real draw

was the leisure and his friendship with “Miss Cammie,” who soon became “Aunt

Cammie.”

Saxon's fiction included short stories: "Cane River" was published in The

Dial magazine edited by Marianne Moore, and "The Centaur Plays Croquet" was

included in the American Caravan anthology in 1927.

He was a director to the Federal Writers' Project, WPA guide to Louisiana.[6]

In 1937, fourteen years after he started it, Saxon finished Children of

Strangers, set among the mixed-race Creoles who lived near Melrose. That year

he bought his final property in the Quarter, a Madison Street house with a

lovely courtyard where he enjoyed having Joe Gilmore serve him drinks, but in

1944, finances strained yet again, he had to sell it. He and Joe moved to a

suite in the St. Charles Hotel and he began to work on a rambling memoir

disguised as a tribute to Gilmore, his devoted true friend whom he called

“Black Saxon.” (Another friend completed The Friends of Joe Gilmore after

Saxon’s death.)

Saxon was (rightly) impressed by some clay models made by

Richmond

Barthé, encouraged him

to study at the Art Institute of Chicago, and remained a champion of the

sculptor’s work.

Contemporary historians of the city rely heavily on Saxon's works for

reference. In 1986, M.A. Houston wrote a Master of Arts-degree thesis, "The

Shadow of Africa on the Cane: An Examination of Africanisms in the Fiction of

Lyle Saxon and Ada Jack Carver." Ada Jack Carver Snell of Minden was another

Louisiana author who wrote about the Cane River country of her native

Natchitoches Parish.

In 1926 Pelican Bookshop Press, New Orleans, published "William Spratling and William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles: A Gallery of Contemporary New Orleans",

issued in 250 copies. The “Famous Creoles” (with ages in 1926) were

- Conrad Albrizio, 27, New York-born, serious artist, Spratling’s neighbor, Arts and Crafts Club stalwart

- Sherwood Anderson, 50, “Lion of the Latin Quarter,” eminence gris, generous to respectful younger writers

(LGBTQ friendly)

- Marc Antony and Lucille Godchaux Antony, both 28, Love-match between heiress and lower-middle-class boy, local artists

- Hamilton “Ham” Basso, 22, Star-struck recent Tulane grad, aspiring writer, good dancer

(LGBTQ friendly)

- Charles “Uncle Charlie” Bein, 35, Director of Arts and Crafts Club’s art school; lived with mother, sister, and aunt

(GAY)

- Frans Blom, 33, Danish archeologist of Maya, Tulane professor, colorful resident of Quarter

- Roark Bradford, 30, Newspaperman, jokester, hit pay dirt with Negro dialect stories

- Nathaniel Cortlandt Curtis, 45, Tulane architecture professor, preservationist, recorded old buildings

- Albert Bledsoe Dinwiddie, 55, President of Tulane, Presbyterian

- Marian Draper, 20, Ziegfeld Follies alum, Tulane cheerleader, prize-winning architecture student

- Caroline “Carrie” Wogan Durieux, 30, Genuine Creole, talented artist living in Cuba and Mexico, painted by

Rivera

- William “Bill” Faulkner, 29, Needs no introduction, but wrote the one to

Famous Creoles (LGBTQ friendly)

- Flo Field, 50, French Quarter guide, ex-journalist, sometime playwright, single mother

- Louis Andrews Fischer, 25, Gender-bending Mardi Gras designer, named for her father

(LGBTQ friendly)

- Meigs O. Frost, 44, Reporter’s reporter; lived in Quarter; covered crime, revolutions, and arts

- Samuel Louis “Sam” Gilmore, 27, Greenery-yallery poet and playwright, from prominent family

(GAY)

- Moise Goldstein, 44, Versatile and successful architect, preservationist, active in Arts and Crafts Club

- Weeks Hall, 32, Master of and slave to Shadows-on-the-Teche plantation, painter, deeply strange

(GAY)

- Ronald Hargrave, 44, Painter from Illinois formerly active in Quarter art scene, relocated to Majorca

- R. Emmet Kennedy, 49, Working-class Irish boy, collected and performed Negro songs and stories

- Grace King, 74, Grande dame of local color literature and no-fault history,

salonnière

- Alberta Kinsey, 51, Quaker spinster, Quarter pioneer, indefatigable painter of courtyards

- Richard R. Kirk, 49, Tulane English professor and poet, loyal Michigan Wolverine alumnus

- Oliver La Farge, 25, New England Brahmin, Tulane anthropologist and fiction-writer, liked a party

- Harold Levy, 32, Musician who ran family’s box factory, knew everybody, turned up everywhere

- Lillian Friend Marcus, 35, Young widow from wealthy family, angel and manager of

Double Dealer (LGBTQ friendly)

- John “Jack” McClure, 33, Poet, newspaper columnist and reviewer,

Double Dealer editor,

bookshop owner

- Virginia Parker Nagle, 29, Promising artist, governor’s niece, Arts and Crafts Club teacher

- Louise Jonas “Mother” Nixon, 70, A founder of Le Petit Theatre and its president-for-life, well-connected widow

- William C. “Cicero” Odiorne, 45, Louche photographer, Famous Creoles’ Paris contact

(GAY)

- Frederick “Freddie” Oechsner, 24, Recent Tulane graduate, ambitious cub reporter, amateur actor

- Genevieve “Jenny” Pitot, 25, Old-family Creole, classical pianist living in New York, party girl

-

Lyle Saxon, 35, Journalist, raconteur, bon vivant, host, preservationist, bachelor

(GAY)

- Helen Pitkin Schertz, 56, Clubwoman, civic activist, French Quarter guide, writer, harpist

- Natalie Scott, 36, Journalist, equestrian, real-estate investor, Junior Leaguer, social organizer

(LGBTQ friendly)

- William “Bill” Spratling, 25, Famous Creoles

illustrator, Tulane teacher, lynchpin of Quarter social life (GAY)

- Keith Temple, 27, Australian editorial cartoonist, artist, sometimes pretended to be a bishop

- Fanny Craig Ventadour, 29, Painter, Arts and Crafts Club regular, lately married and living in France

- Elizebeth Werlein, 39, Suffragette with colorful past, crusading preservationist, businessman’s widow

- Joseph Woodson “Pops” Whitesell, 50, Photographic jack-of-all-trades, French Quarter eccentric, inventor

(GAY)

- Daniel “Dan” Whitney, 32, Arts and Crafts Club teacher, married (two) students, beauty pageant judge

- Ellsworth Woodward, 65, Artistic elder statesman, old-fashioned founder of Newcomb art department

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyle_Saxon

- http://www.glbtqarchive.com/literature/saxon_lc_L.pdf

- Reed, John Shelton. Dixie Bohemia: A French Quarter

Circle in the 1920s (Walter Lynwood Fleming Lectures in Southern History)

(p.22). LSU Press. Edizione del Kindle.

Lyle

Chambers Saxon (September 4, 1891 – April 9, 1946) was a respected New Orleans writer and journalist

who reported for The Times-Picayune. It has been suggested that his only great love was his childhood friend,

George Favrot, who died young

in 1925. Other sources maintain that he had a sexual relationship with Joe Gilmore, his long-time black valet. Biographer James W. Thomas interviewed many of Saxon's closest friends and concluded, "Saxon'shomosexual affairs were discreet, never a problem for his heterosexual friends, and not a significant partof his literary life."

Saxon’s biographer Chance Harvey says that Thomas C. Atkinson of Baton Rouge

told her that Saxon and his friend George Favrot were caught “in drag” and

expelled from school, but that Atkinson offered no corroboration.

Lyle

Chambers Saxon (September 4, 1891 – April 9, 1946) was a respected New Orleans writer and journalist

who reported for The Times-Picayune. It has been suggested that his only great love was his childhood friend,

George Favrot, who died young

in 1925. Other sources maintain that he had a sexual relationship with Joe Gilmore, his long-time black valet. Biographer James W. Thomas interviewed many of Saxon's closest friends and concluded, "Saxon'shomosexual affairs were discreet, never a problem for his heterosexual friends, and not a significant partof his literary life."

Saxon’s biographer Chance Harvey says that Thomas C. Atkinson of Baton Rouge

told her that Saxon and his friend George Favrot were caught “in drag” and

expelled from school, but that Atkinson offered no corroboration.