Queer Places:

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

11–14 Hinde Street, Marylebone W1U 3BG

St Andrew’s Mansions, 3 Dorset St, Marylebone, London W1U 6QU

Luxborough House, 7 Luxborough St, Marylebone, London W1U 5BJ

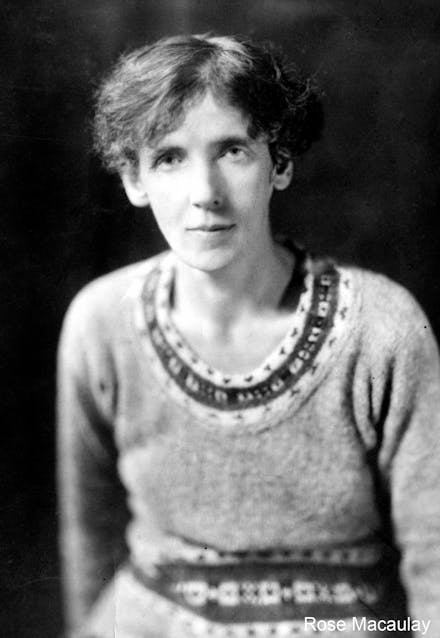

Dame Emilie Rose Macaulay, DBE (1

August 1881 – 30 October 1958) was an English writer, most noted for her

award-winning novel The

Towers of Trebizond, about a small Anglo-Catholic group

crossing Turkey by camel. The story is seen as a spiritual autobiography,

reflecting her own changing and conflicting beliefs. Macaulay's novels were

partly influenced by Virginia

Woolf; she also wrote biographies and travelogues. The successful

journalist and novelist Naomi

Royde-Smith, the first woman to write the literature editorship of

the Saturday Westminster Gazettein 1912, ran a small literary salon with Rose

Macaulay in her apartment in Queensgate, Kensington. Both were friends with

Theodora Bosanquet.

Rose Macaulay was a close friend of

Sylvia Lynd, Vera

Brittain, Storm Jameson,

Mary Agnes Hamilton and

Virginia Woolf.

Dame Emilie Rose Macaulay, DBE (1

August 1881 – 30 October 1958) was an English writer, most noted for her

award-winning novel The

Towers of Trebizond, about a small Anglo-Catholic group

crossing Turkey by camel. The story is seen as a spiritual autobiography,

reflecting her own changing and conflicting beliefs. Macaulay's novels were

partly influenced by Virginia

Woolf; she also wrote biographies and travelogues. The successful

journalist and novelist Naomi

Royde-Smith, the first woman to write the literature editorship of

the Saturday Westminster Gazettein 1912, ran a small literary salon with Rose

Macaulay in her apartment in Queensgate, Kensington. Both were friends with

Theodora Bosanquet.

Rose Macaulay was a close friend of

Sylvia Lynd, Vera

Brittain, Storm Jameson,

Mary Agnes Hamilton and

Virginia Woolf.

Macaulay was born in Rugby, Warwickshire the daughter of George Campbell Macaulay, a Classical scholar, and his wife, Grace Mary Conybeare. Her father was descended in the male-line directly from the Macaulay family of Lewis. She was educated at Oxford High School for Girls and read Modern History at Somerville College at Oxford University.[1]

Macaulay began writing her first novel, Abbots Verney (published 1906), after leaving Somerville and while living with her parents at Ty Isaf, near Aberystwyth, in Wales. Later novels include The Lee Shore (1912), Potterism (1920), Dangerous Ages (1921), Told by an Idiot (1923), And No Man's Wit (1940), The World My Wilderness (1950), and The Towers of Trebizond (1956). Her non-fiction work includes They Went to Portugal, Catchwords and Claptrap, a biography of John Milton, and Pleasure of Ruins. Macaulay's fiction was influenced by Virginia Woolf and Anatole France.[2] During World War I Macaulay worked in the British Propaganda Department, after some time as a nurse and later as a civil servant in the War Office. She pursued a romantic affair with Gerald O'Donovan, a writer and former Jesuit priest, whom she met in 1918; the relationship lasted until his death, in 1942.[3]

On 16 June 1932, at the Dorchester Hotel on Park Lane, London, a number of British women writers and readers gathered for a Reception given by Time and Tide, the feminist weekly newspaper founded by Lady Margaret Rhondda in 1920. According to a report printed in The Times the next day, among those who had accepted invitations to be present were: Phyllis Bentley, Stella Benson, Vera Brittain, Professor Winifred Cullis, E.M. Delafield, Susan Ertz, Eleanor Farjeon, Cicely Hamilton, Winifred Holtby, Sylvia Lynd, Rose Macaulay, Naomi Mitchison, Edith Shackleton, Rebecca West and Ellen Wilkinson. Years later, Naomi Mitchison described Time and Tide as 'the first avowedly feminist literary journal with any class, in some ways ahead of its time', which in the early 1930s was 'in full flood, with a number of good authors writing for it'.

During the interwar period Macaulay was a sponsor of the pacifist Peace Pledge Union; however she resigned from the PPU and later recanted her pacifism in 1940.[4] Her London flat was utterly destroyed in the Blitz, and she had to rebuild her life and library from scratch, as documented in the semi-autobiographical short story, Miss Anstruther's Letters, which was published in 1942. The Towers of Trebizond, her final novel, is generally regarded as her masterpiece. Strongly autobiographical, it treats with wistful humour and deep sadness the attractions of mystical Christianity, and the irremediable conflict between adulterous love and the demands of the Christian faith. For this work, she received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1956.

Macaulay was never a simple believer in "mere Christianity", and her writings reveal a more complex, mystical sense of the Divine. That said, she did not return to the Anglican church until 1953; she had been an ardent secularist before and, while religious themes pervade her novels, previous to her conversion she often treats Christianity satirically, for instance in Going Abroad and The World My Wilderness. She never married, as a result of her lengthy and secret relationship with Gerald O'Donovan. She was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) on 31 December 1957 in the 1958 New Years Honours[7] and died ten months later, on 30 October 1958, aged 77, an active feminist throughout her life.[2].

My published books: