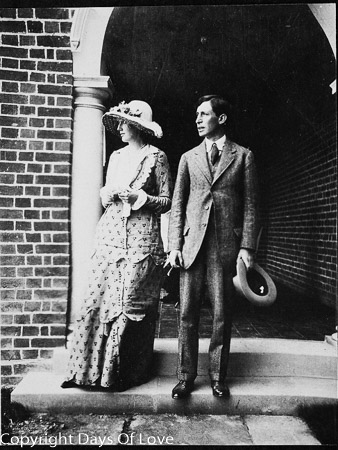

Husband Leonard Woolf

Queer Places:

Talland House, Albert Rd, Saint Ives TR26, UK

9 St Aubyns, Hove BN3 2TG, UK

Burley House, 15 Cambridge Park, Twickenham TW1 2JE, UK

22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington, London SW7 5DH, UK

29 Fitzroy Square, Fitzrovia, London W1T, UK

46 Gordon Square, Kings Cross, London WC1H 0PD, UK

52 Tavistock Square, Kings Cross, London WC1H, UK

38 Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1AE, UK

37 Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1N, UK

King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, UK

Asham House, Beddingham, Lewes BN8, UK

17 Portland Terrace, The Green, Richmond TW9 1QQ, UK

Hogarth House, 34 Paradise Rd, Richmond TW9 1SE, UK

The Round House, Pipe Passage, Lewes BN7 1YQ, UK

Monk’s House, Rodmell, Lewes BN7 3HF, UK

Adeline

Virginia Woolf (née Stephen; 25 January 1882 – 28 March 1941) was an English

writer who is considered one of the most important modernist twentieth century

authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative

device. Identified with the Lost

Generation. Virginia Woolf dedicated Orlando (1928), "To

V.

Sackville-West". Sackville-West's travels in France were many, and

made quite frequently with her women lovers and companions - notable, of

course, with Violet Trefusis, but also with

Evelyn Irons, with

Gwen St Aubyn,

and most famously, with Virginia Woolf.

Woolf was acquainted with May

Sarton. Virginia Woolf was a close friend of

Rose Macaulay,

Margaret Rhondda,

Winifred Holtby

and Stella Benson.

Adeline

Virginia Woolf (née Stephen; 25 January 1882 – 28 March 1941) was an English

writer who is considered one of the most important modernist twentieth century

authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative

device. Identified with the Lost

Generation. Virginia Woolf dedicated Orlando (1928), "To

V.

Sackville-West". Sackville-West's travels in France were many, and

made quite frequently with her women lovers and companions - notable, of

course, with Violet Trefusis, but also with

Evelyn Irons, with

Gwen St Aubyn,

and most famously, with Virginia Woolf.

Woolf was acquainted with May

Sarton. Virginia Woolf was a close friend of

Rose Macaulay,

Margaret Rhondda,

Winifred Holtby

and Stella Benson.

The 1920s were boom years for lesbian literature, seeing the publication of a large range of texts from virulently anti-lesbian works, such as Compton MacKenzie's Extraordinary Women (1928), through relatively traditional celebrations of romantic friendship, such as Elizabeth Bowen's The Hotel (1927), to radical modernist texts with encoded lesbian themes, such as Virginia Woolf's Orlando (1928). The highbrow novelist Virginia Woolf was able to present same-sex desire in her modernist novel Orlando. Her social postion, as an established novelist and critic, a married woman, and a member of London society, placed Woolf in a potentially more vulnerable situation than her expatriate contemporaries. Despite this, Virginia Woolf's Orlando, published only months after The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall and treating the subject of lesbianism in a much more positive light, escaped suppression to become a mainstream best-seller. The novel was written for, and dedicated to, Vita Sackville-West and was subsequently described by Vita's son, Nigel, as the longest and most charming love-letter in literature. Historians and biographers continue to be divided over the extent to which Vita and Virginia's relationship was lesbian. However, Virginia Woolf's own diary entries and her frequent letters to Vita suggest that she did care passionately for her. In one letter she declared: But I fo adore you, every part of you from heel to hair. Never will you shake me off, try as you may... But if being loved by Virginia is any good, she does do that; and always will, and please believe it. She wrote to Vita up to four times a week furing the height of their relationship, and although Virginia was particularly circumspect about their meetings, even in the privacy of her own diary, their private correspondence gives some indication of the nature of their relationship. Virginia Woolf's letters reveal a playful coyness: Should you say, if I rang up to ask, that you were fond of me? If I saw you would you kiss me? If I were in bed would you, I'm rather excited about Orland tonight: Have been lying by the fire and making up the last chapter.

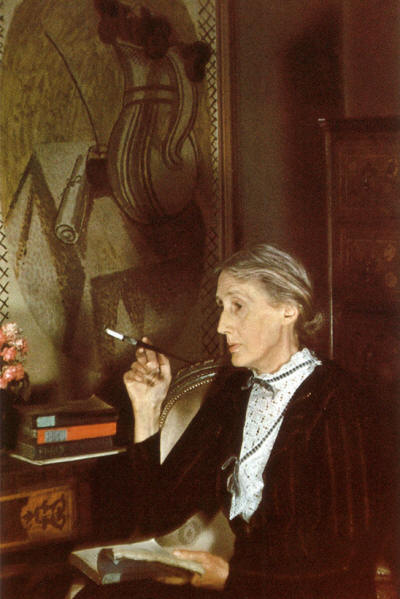

Gisèle Freund (French, born Germany 1908-2000)

Virginia Woolf

1939

© Gisèle Freund

Virginia Woolf, 1939, by Gisèle Freund

Virginia Woolf, 1939, by Gisèle Freund

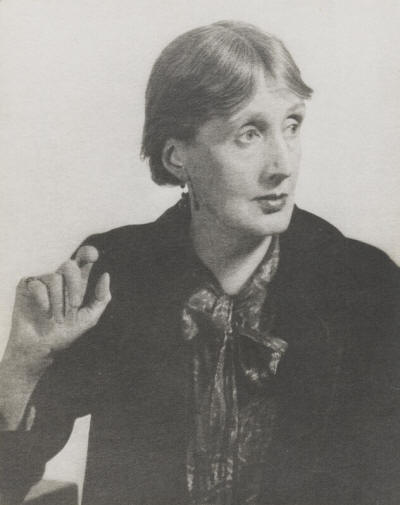

Virginia Woolf, by Man Ray, 1934

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

by Roger Fry,

Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds Museums and Galleries

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) c.1912

Vanessa Bell (1879–1961)

National Trust, Monk's House

Katherine Stephen, Virginia Woolf's aunt, by

Glyn Warren Philpot

The Green, Richmond

The Round House

Monk's House

Virginia Woolf was born in an affluent household in South Kensington, London, attended the Ladies' Department of King's College and was acquainted with the early reformers of women's higher education. Having been home-schooled for the most part of her childhood, mostly in English classics and Victorian literature, Woolf began writing professionally in 1900. During the interwar period, Virginia Woolf was an important part of London's literary society as well as a central figure in the group of intellectuals known as the Bloomsbury Group. She published her first novel titled The Voyage Out in 1915, through her half-brother’s publishing house, Gerald Duckworth and Company. Her best-known works include the novels Mrs Dalloway (1925), To the Lighthouse (1927) and Orlando (1928). She is also known for her essay A Room of One's Own (1929),[4] where she wrote the much-quoted dictum, "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction."

When Thoby went up to Trinity in 1899 he became friends with a circle of young men, including Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, Saxon Sydney-Turner, that he would soon introduce to his sisters at the Trinity May Ball in 1900. These men formed a reading group they named the Midnight Society.[105][106] Despite his low material status (Woolf referring to Leonard during their engagement as a "penniless Jew") the couple shared a close bond. Indeed, in 1937, Woolf wrote in her diary: "Love-making—after 25 years can't bear to be separate ... you see it is enormous pleasure being wanted: a wife. And our marriage so complete."[155] However, Virginia made a suicide attempt in 1913.[144]

The ethos of the Bloomsbury group encouraged a liberal approach to sexuality, and in December 1922 she met the writer and gardener Vita Sackville-West,[161] wife of Harold Nicolson. At the time, Sackville-West was the more successful writer both commercially and critically, and it was not until after Woolf's death that she became considered the better writer.[176] After a tentative start, they began a sexual relationship, which, according to Sackville-West in a letter to her husband dated 17 August 1926, was only twice consummated.[177] However, Virginia's intimacy with Vita seems to have continued into the early 1930s.[178] Woolf was also inclined to brag of her affairs with other women within her intimate circle, such as Sibyl Colefax and Winnaretta Singer.[179] Woolf was also a close friend of Dorothy Brett.

In 1928, Woolf presented Sackville-West with Orlando,[164] a fantastical biography in which the eponymous hero's life spans three centuries and both sexes. Nigel Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West's son, wrote, "The effect of Vita on Virginia is all contained in Orlando, the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which she explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her."[181] After their affair ended, the two women remained friends until Woolf's death in 1941. Virginia Woolf also remained close to her surviving siblings, Adrian and Vanessa; Thoby had died of typhoid fever at the age of 26.[182] Later Adrian married Karin Stephen, a British psychoanalyst and psychologist.

In 1930, after dining with various homosexual men, including E.M. Forster and Lytton Strachey, whose conversation strayed on to the topic of attractive youths, Virginia Woolf said she had received ‘a tinkling, private, giggling impression. As if I had gone into a men’s urinal.’ Of Eddy Sackville-West she said, quite simply, ‘I can’t take Buggerage seriously.’ Hermione Lee, her biographer, comments, as follows: ‘Like Simone de Beauvoir twenty years later … the feminist in her deplored the fact that gay men seemed to want to be women. And she must also have felt that homosexuality was, for the next generation of writers, an exclusive exclusive passport for literary success.’

Vita Sackville-West worked tirelessly to lift up Woolf's self-esteem, encouraging her not to view herself as a quasi-reclusive inclined to sickness who should hide herself away from the world, but rather offered praise for her liveliness and sense of wit, her health, her intelligence and achievements as a writer.[180] Sackville-West led Woolf to reappraise herself, developing a more positive self-image, and the feeling that her writings were the products of her strengths rather than her weakness.[180] Starting at the age of 15, Woolf had believed the diagnosis by her father and his doctor that reading and writing were deleterious to her nervous condition, requiring a regime of physical labour such as gardening to prevent a total nervous collapse. This led Woolf to spend much time obsessively engaging in such physical labour.[180] Sackville-West was the first to argue to Woolf she had been misdiagnosed, and that it was far better to engage in reading and writing to calm her nerves—advice that was taken.[180] Under the influence of Sackville-West, Woolf learned to deal with her nervous ailments by switching between various forms of intellectual activities such as reading, writing and book reviews, instead of spending her time in physical activities that sapped her strength and worsened her nerves.[180] Sackville-West chose the financially struggling Hogarth Press as her publisher in order to assist the Woolfs financially. Seducers in Ecuador, the first of the novels by Sackville-West published by Hogarth, was not a success, selling only 1500 copies in its first year, but the next Sackville-West novel they published, The Edwardians, was a bestseller that sold 30,000 copies in its first six months.[180] Sackville-West's novels, though not typical of the Hogarth Press, saved Hogarth, taking them from the red into the black.[180] However, Woolf was not always appreciative of the fact that it was Sackville-West's books that kept the Hogarth Press profitable, writing dismissively in 1933 of her "servant girl" novels.[180] The financial security allowed by the good sales of Sackville-West's novels in turn allowed Woolf to engage in more experimental work, such as The Waves, as Woolf had to be cautious when she depended upon Hogarth entirely for her income.[180]

After completing the manuscript of her last novel (posthumously published), Between the Acts (1941),[210] Woolf fell into a depression similar to that which she had earlier experienced. The onset of World War II, the destruction of her London home during the Blitz, and the cool reception given to her biography[211] of her late friend Roger Fry all worsened her condition until she was unable to work.[212] When Leonard enlisted in the Home Guard, Virginia disapproved. She held fast to her pacifism and criticized her husband for wearing what she considered to be the silly uniform of the Home Guard.[213] After World War II began, Woolf's diary indicates that she was obsessed with death, which figured more and more as her mood darkened.[214] On 28 March 1941, Woolf drowned herself by filling her overcoat pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse near her home.[215] Her body was not found until 18 April.[216] Her husband buried her cremated remains beneath an elm tree in the garden of Monk's House, their home in Rodmell, Sussex.[217]

Woolf became one of the central subjects of the 1970s movement of feminist criticism, and her works have since garnered much attention and widespread commentary for "inspiring feminism", an aspect of her writing that was unheralded earlier. Her works are widely read all over the world and have been translated into more than fifty languages. She suffered from severe bouts of mental illness throughout her life and took her own life by drowning in 1941 at the age of 59.

My published books: