BURIED TOGETHER

Partner

John Marshall, buried together

Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

Lewes House, 23 High St, Lewes BN7 2LU, Regno Unito

Cimitero Inglese di Bagni di Lucca, Via Letizia, 55022 Bagni di Lucca LU, Italia

Edward

Perry Warren (January 8, 1860 – December 28, 1928), known as Ned Warren,

was an American art collector and the author of works proposing an

idealized view of homosexual relationships. He is now best known as the

former owner of the Warren Cup in the British Museum.

Edward

Perry Warren (January 8, 1860 – December 28, 1928), known as Ned Warren,

was an American art collector and the author of works proposing an

idealized view of homosexual relationships. He is now best known as the

former owner of the Warren Cup in the British Museum.

Warren was born on January 8, 1860, in Waltham, Massachusetts,[1]

one of five children born into of a wealthy Boston, Massachusetts family.

He was the son of Samuel Denis Warren (1817-1888), who founded the

Cumberland Paper Mills in Maine, and Susan Cornelia Clarke (1825-1901),

the daughter of Dorus Clarke.[2][3]

He had four siblings:

Samuel Dennis Warren II (1852-1910), lawyer and businessman;

Henry Clarke Warren (1854-1899), scholar of Sanskrit and Pali;

Cornelia Lyman Warren (1857-1921), philanthropist;

Fredrick Fiske Warren (1862-1938), political radical and utopist.[2]

Ned Warren received his B.A. from Harvard College in 1883[1]

and later studied at New College, Oxford, earning his M.S. in Classics.[3]

His academic interest was classical archeology. At Oxford he met

archeologist

John Marshall (1860–1928),[4]

with whom he formed a close and long-lasting relationship, though Marshall

married in 1907, much to Warren's dismay.[4]

Lewes House, Lewes

.JPG)

Cimitero Inglese di Bagni di Lucca, Via Letizia, 55022 Bagni di Lucca LU, Italia

In the late 1870s Ned Warren attended St. Stephen Church in Boston, then

located on Florence St. in the South End. He found it to be a good

middle ground between the overwhelming presence of

Phillips Brooks (another

man who never married and about whom there were whispered questions

regarding his sexuality) at Trinity Church and the intensity of services

at the Anglican Church of the Advent on Beacon Hill. Warren graduated

from Harvard dissatisfied romantically. He was constantly falling in

love with his friends, but awkwardness and decorum prevented him from

having sustained relationships.

In 1875 John Lowell "Jack" Gardner's brother, Joseph P. Gardner, committed suicide, leaving three young

sons, Joseph Peabody, William Amory and Augustus Peabody. Jack and Isabella

Stewart Gardner adopted and raised the boys. In 1886,

Joseph Peabody Gardner, Jr., committed suicide like his father.

Douglass Shand-Tucci believes he killed himself because of his unrequited love for another man. Augustus Peabody Gardner became a military officer, a U.S. congressman and son-in-law of Henry Cabot Lodge.

William Amory Gardner was probably the lover of

Ned Warren, the benefactor of the Museum of Fine Arts. And Shand-Tucci recounts this anecdote about Amory, when he was a don at the then-new Groton School. A young boy brought a minister to William Amory Gardner’s room for a visit after chapel. The visitors having arrived at what turned out to be Gardner’s bedroom, it was at once clear that not only was W.A.G. stark naked before the fireplace (except for a pair of voluptuous bedroom slippers) but also so was the young man reclining on the sofa…

Ned’s Harvard years were crowded. He was enraptured by

Oscar Wilde’s Boston lecture of

1882, and though brother Sam talked him out of a tête-à-tête with Wilde,

Warren met him later in New York.

Charles Eliot Norton, one of the foremost scholars of archeology in the United

States, had four protégés in the 1880s. Three were gay:

George Santayana,

Charles Loeser, who after a lifetime in

Florence bequeathed 8 paintings by Cezanne to the White House and

Logan Pearsall Smith. The

fourth, Bernard Berenson, was

straight but was very accomodating to his gay friends. All four were frequent

visitors to the Gardners. Also at Harvard was newphew Joe Gardner Jr, who

lived across the hall from Ned Warren

and was friends with the four protégés. Joe was in love with Smith and after

graduating, he bought a retreat in Hamilton, Massachusetts purchased as a

place he could spend time with Smith. For a while the relationship was happy

and Smith went up to Hamilton quite frequently, often bringing his sister,

Mary Smith (who eventually married

Berenson, her second husband, in 1900). Smith eventually lost interest in Joe.

The lovesick young man, who frequently suffered from depression, committed

suicide on October 10, 1886. Isabella and Jack were brokenhearted while Smith

departed for Oxford and a career as a essayist and social critic in England.

In Boston, Warren began to emerge as something of a mentor to younger

men often not from Warren’s sort of privileged background. Among these was

perhaps his most brilliant protégé, Bernard Berenson,

then an obscure if charming Boston University freshman. It was Warren who

discovered “B.B.,” helping him transfer into Harvard and introducing him

not just to Boston society, but to the great world, where Berenson would

encounter, among others, his great patron, Isabella Stewart Gardner. It

was Warren who (with Gardner and others) funded Berenson’s first study

trip to Europe in 1887, a journey from which in a very real sense the

young man—soon to become the world’s leading authority on the attribution

of Italian Renaissance painting—never returned. Warren also subsidized

Berenson when others withdrew, enabling him to remain in Europe.

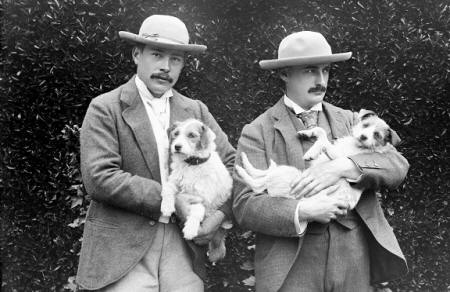

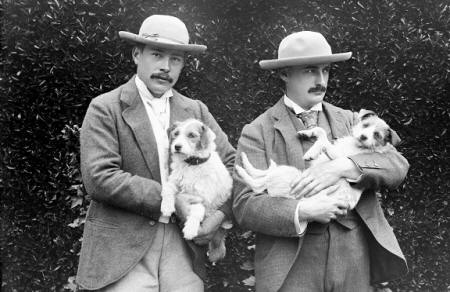

Beginning in 1888, Warren made England his primary home. Warren settled

with his Oxford classmate, the classicist

John Marshall. He was not

easily won, but after an 1889 buying trip to Rome and the discovery of an

English country house he liked south of London at Lewes, Marshall accepted

Warren’s proposal and they embarked on a relationship as personal as it

was artistic, dedicating themselves to the acquisition of what the author

of the Bowdoin article aptly calls “works of a school of art whose highest

ideal of beauty was found in the nude body of the young male athlete.”

Ultimately Warren and Marshall came to share not only their great task but

their own joint protégés, among them

John Davidson Beazley, very

much the golden youth, an Oxford undergraduate who would later virtually

invent the study of ancient Greek Attic pottery.

Warren and Marshall

lived together at Lewes House, a large residence in Lewes, East Sussex,

where they became the center of a circle of like-minded men interested in

art and antiquities who ate together in a dining room overlooked by Lucas

Cranach's Adam and Eve—a gift of

Harold W. Parsons[2]—now

in the Courtauld Institute of Art. One account said that "Warren's

attempts to produce a supposedly Greek and virile way of living into his

Sussex home" produced "a comic mixture of apparently monastic severity (no

tea or soft chairs allowed) and lavish living."[5]

Warren spent much of his time in Continental Europe collecting art

works, many of which he donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

assembling for that institution the "largest collection of erotic Greek

vase paintings " in the U.S.[6]

He has been described as having "a taste for pornography" and was a

"pioneer" in collecting it.[7]

His published works include A Defence of Uranian Love in three

volumes, which proposes a type of same-sex relationship similar to that

prevalent in Classical Greece, in which an older man would act as guide

and lover to a younger man.

Samuel Warren began to oppose the dealings with his brother and brought

in Matthew Pritchard to

be secretary to Edward Robinson at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, to

stumie his brother's purchases. Pritchard was soon charmed by Warren,

however. Sent to keep an eye on Warren, Pritchard went to Lewes and

quickly became part of the household. He was "over six feet hall, with

spare athletic body, a long rather cadaverous face, and long, thin,

nervous hands." He taught many of the men at Lewes how to swim (going

into the water naked was de rigueur) and he was an accomplished horse

rider. Pritchard taught himself Turkish and Arabic by memorizing words

while shaving and "in the streets of Lewes he wore a Turkish fez, walked

in the middle of the road with an abstracted air, impervious to the

jibes and jeers of the locals, salaamed on entering a room, used Turkish

or Arabic phrases on greeting and departure, and gave the impression

that he had a private working-relationship with Allah." Later he would

be hired by

Isabella Stewart Gardner to assist with her museum.

In 1900 Warren published The Prince who did not Exist, a small

edition art book from the Merrymount Press, "a most beautiful specimen of

workmanship" according to the New York Times.[8]

Warren's oldest brother, Samuel D. Warren had left law to work in

managing the family's paper mills. He managed the family trust established

in May 1889 with the legal assistance of Louis D. Brandeis to benefit his

father's widow and five children. Edward Warren challenged the family

trust in 1906, claiming that Brandeis had structured it to benefit his law

partner Samuel to the detriment of the other family members. The dispute

ended with Samuel's suicide in 1910.[9]

The Warren Trust case became a point of contention during the 1916 Senate

hearings on the confirmation of Brandeis to the Supreme Court and it

remains important for its explication of legal ethics and professional

responsibility.[10]

Warren purchased the Roman silver drinking vessel known as the Warren

Cup, now in the British Museum, which he did not attempt to sell during

his lifetime because of its explicit depiction of homoerotic scenes. He

also commissioned a version of The Kiss from Auguste Rodin, which

he offered as a gift to the local council in Lewes. The council displayed

it for two years before returning it as unsuitable for public display.[3]

It is now in the Tate Gallery.[11]

In 1911 Warren adopted a four-year-old child, Travis. The child grew up

at Lewes House and Fewacres, calling Warren "Papa". He was the

illegitimate son of the daughter of a Cornish vicar and a local squire.

Warren told Lois Shaw, a relative and friend: "I think that I have found a

boy to adopt, but shall not know till my return to England. He is of good

birth and healthy. I am a little afraid of him, because he seems likely to

be of some account and therefore troublesome." Warren later said "if it is

to be this boy, this handful, he must have a man about, to take after. I

won't do: I know that. Harry [H. Asa Thomas, Warren's secretary] would. He

admires Harry, but Harry hates his tantrums. Harry, you see, is not keen

on children. Neither am I." Travis Warren attended Winchester College. He

was not a good student and he changed schools, going to Tonbridge School.[2]

George Santayana spent a

lot of time with fellow Harvard graduate Ned Warren in Europe,

particularly when Santayana was writing The Last Puritan. Despite Boston's

tolerance, Santayana was frustrated by its conservatism. He "could either

stay in the city, pursue a career in business while withering and "folds

up his heat" or he could flee to Oxford or Montmartre and save his soul...

Santayana chose his soul.

Warren had a home, Fewacres, in Westbrook, Maine, near the Paper Mills

of his father, and Marshall had a home in Rome.[1]

After the death of Mary Bliss Marshall in 1925, Marshall spent always more

time at Lewes House, where he died in 1928. John Marshall's will named

Warren as his executor and beneficiary.[1][2]

According to Martin Burgess Green, author of The Mount Vernon Street Warrens: a Boston story, 1860-1910, of all the men who gravitated around

Warren, the most important was John Marshall.

John Fothergill, Warren's friend and biographer, reports that Warren

composed the following epigraph: "Here lies Edward Perry Warren, friend to

John Marshall ... the finest judge of Greek and Roman antiquities." He

reported Marshall's death date but not his own.

J. D. Beazley said that "Warren always spoke of Marshall (over

generously) as in a class much superior to himself as an archaeologist."

According to Green, "the relationship was intellectually and emotionally

unequal. But there was some reciprocity, as well as this one-sided

adoration. Each called the other Puppy, and in their later years,

according to Burdett and Goddard, they came to resemble each other,

looking like twin Punchinellos walking arm in arm together."[2]

Later that year, Warren became seriously ill and underwent surgery.[3]

He died in a London nursing home on December 28, 1928.[1]

His ashes were buried in the non-Catholic cemetery in

Bagni di Lucca, Italy,[12]

a town known as a spa in Etruscan and Roman times. In the same tomb are

buried John Marshall and the latter's wife, Mary.

In March 1928, Warren had already given Lewes House and its adjoining

properties to H. Asa Thomas, who had begun as his secretary and become his

business associate and friend; meanwhile, Fewacres and its adjoining

properties went to Charles Murray West, his other secretary.[3]

Both Thomas and West sold the properties few years after Warren's death.

Travis Warren inherited $3,000 a year managed by his guardians (Thomas and

Burdett) up to the age of twenty-eight. From 28 to 32 years old he was to

receive $20,000, and $200 a month, and his guardians could invest up to

$30,000 on his behalf in a business. At the end of the trust, he was to

receive $3,000 a year. Despite all this money, Travis was poor by the end

of his life.[2]

The disposition of Warren's estate was complicated by legal problems.[13]

An auction of some 250 pieces of his furniture brought $38,885.[14]

The

Sackler Library at

Oxford University holds the "Papers of E.P. Warren and John Marshall."[15]

Warren's will established the position of EP Warren

Praelector at

Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and established restrictions, no

longer maintained, that ensured the holder lived at or near the College

and taught only men.[13]

In 2013, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts determined that a bronze

statuette it purchased from Warren in 1904 had been stolen from a French

museum in 1901 and arranged for its return.[16]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Perry_Warren

- Bachelors of a Different Sort, Queer Aesthetics, Material Culture

and the Modern Interior in Britain, by John Potvin

- Homosexuals in History, A Study of Ambivalence in Society,

Literature and the Arts, by A.L. Rowse, 1977

- Improper Bostonians Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to

Playland By History Project Staff · 1998

- The Hub of the Gay Universe, An LGBTQ History of Boston,

Provincetown, and Beyond, by Russ Lopez, 2019

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass. The Crimson Letter . St. Martin's

Publishing Group. Edizione del Kindle.

Edward

Perry Warren (January 8, 1860 – December 28, 1928), known as Ned Warren,

was an American art collector and the author of works proposing an

idealized view of homosexual relationships. He is now best known as the

former owner of the Warren Cup in the British Museum.

Edward

Perry Warren (January 8, 1860 – December 28, 1928), known as Ned Warren,

was an American art collector and the author of works proposing an

idealized view of homosexual relationships. He is now best known as the

former owner of the Warren Cup in the British Museum.

.JPG)