Wife Mary Berenson

Queer

Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Villa I Tatti, Via Vincigliata, 26, 50014 Fiesole FI

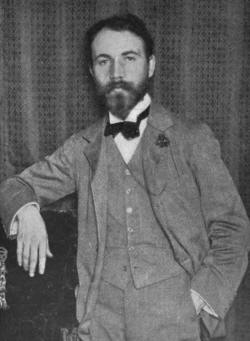

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book Drawings of the Florentine Painters was an international success. His wife

Mary Berenson is thought to have had a large hand in some of the writings.[2]

Berenson was a major figure in the attribution of Old Masters, at a time when these were attracting new interest by American collectors, and his judgments were widely respected in the art world. Recent research has cast doubt on some of his authentications, which may have been influenced by the exceptionally high commissions paid to him.

Bernard Berenson (June 26, 1865 – October 6, 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book Drawings of the Florentine Painters was an international success. His wife

Mary Berenson is thought to have had a large hand in some of the writings.[2]

Berenson was a major figure in the attribution of Old Masters, at a time when these were attracting new interest by American collectors, and his judgments were widely respected in the art world. Recent research has cast doubt on some of his authentications, which may have been influenced by the exceptionally high commissions paid to him.

Berenson was born Bernhard Valvrojenski in Butrimonys, Vilnius Governorate (now in Alytus district of Lithuania) to a Litvak family – father Albert Valvrojenski, mother Judith Mickleshanski, and younger siblings including Senda Berenson Abbott.[3] His father Albert grew up following an educational track of classical Jewish learning and contemplated becoming a rabbi. However, he became a practitioner of Haskalah, a European movement which advocated more integration of Jews into secular society. After his home and lumber business were burned to the ground, he lived with his more traditionalist in-laws who pressured him to enroll Bernard with a Hebrew and Aramaic tutor. They emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts from the Vilnius Governorate of the Russian Empire in 1875, whereupon the family name was changed to "Berenson." Berenson converted to Christianity in 1885, becoming an Episcopalian.[4] Later, while living in Italy, he converted to Catholicism.[5][6][7] After graduating from Boston Latin School he attended the Boston University College of Liberal Arts as a freshman during 1883–84, but, unable to obtain instruction in Sanskrit from that institution, transferred to Harvard University for his sophomore year.[8]

In Boston, Edward Perry Warren began to emerge as something of a mentor to younger men often not from Warren’s sort of privileged background. Among these was perhaps his most brilliant protégé, Bernard Berenson, then an obscure if charming Boston University freshman. It was Warren who discovered “B.B.,” helping him transfer into Harvard and introducing him not just to Boston society, but to the great world, where Berenson would encounter, among others, his great patron, Isabella Stewart Gardner. It was Warren who (with Gardner and others) funded Berenson’s first study trip to Europe in 1887, a journey from which in a very real sense the young man—soon to become the world’s leading authority on the attribution of Italian Renaissance painting—never returned. Warren also subsidized Berenson when others withdrew, enabling him to remain in Europe.

Cole Porter, Linda Lee Thomas, Bernard Berenson, and Howard Sturges in a gondola, 1923

In 1875 John Lowell "Jack" Gardner's brother, Joseph P. Gardner, committed suicide, leaving three young sons, Joseph Peabody, William Amory and Augustus Peabody. Jack and Isabella Stewart Gardner adopted and raised the boys. In 1886, Joseph Peabody Gardner, Jr., committed suicide like his father. Douglass Shand-Tucci believes he killed himself because of his unrequited love for another man. Augustus Peabody Gardner became a military officer, a U.S. congressman and son-in-law of Henry Cabot Lodge. William Amory Gardner was probably the lover of Ned Warren, the benefactor of the Museum of Fine Arts. And Shand-Tucci recounts this anecdote about Amory, when he was a don at the then-new Groton School. A young boy brought a minister to William Amory Gardner’s room for a visit after chapel. The visitors having arrived at what turned out to be Gardner’s bedroom, it was at once clear that not only was W.A.G. stark naked before the fireplace (except for a pair of voluptuous bedroom slippers) but also so was the young man reclining on the sofa… Charles Eliot Norton, one of the foremost scholars of archeology in the United States, had four protégés in the 1880s. Three were gay: George Santayana, Charles Loeser, who after a lifetime in Florence bequeathed 8 paintings by Cezanne to the White House and Logan Pearsall Smith. The fourth, Bernard Berenson, was straight but was very accomodating to his gay friends. All four were frequent visitors to the Gardners. Also at Harvard was newphew Joe Gardner Jr, who lived across the hall from Ned Warren and was friends with the four protégés. Joe was in love with Smith and after graduating, he bought a retreat in Hamilton, Massachusetts purchased as a place he could spend time with Smith. For a while the relationship was happy and Smith went up to Hamilton quite frequently, often bringing his sister, Mary Smith (who eventually married Berenson, her second husband, in 1900). Smith eventually lost interest in Joe. The lovesick young man, who frequently suffered from depression, committed suicide on October 10, 1886. Isabella and Jack were brokenhearted while Smith departed for Oxford and a career as a essayist and social critic in England.

Berenson graduated from Harvard and married Mary Smith, who became a notable art historian in her own right. Mary was the sister of Logan Pearsall Smith and of Alys Pearsall Smith, the first wife of Bertrand Russell. Mary had previously been married to the Irish barrister Benjamin Conn "Frank" Costelloe. Their two daughters were Ray Strachey and Karin Stephen, in-laws to Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, respectively. Bernard Berenson was also involved in a long relationship with Belle da Costa Greene. Samuels (1987) mentions Mary's "reluctant acceptance (at times)" of this relationship. Among his friends there are: American writer Ray Bradbury, who wrote about their friendship in The Wall Street Journal and in his book of essays, Yestermorrow; Natalie Barney, who lived in Florence during World War II, and also her partner, Romaine Brooks; art collector Edward Perry Warren.[9] His circle of friends also included Isabella Stewart Gardner, Ralph Adams Cram and George Santayana, the latter two having met each other through Bernard.[10] Marisa Berenson, an actress, is a distant cousin of Berenson's through Louis Kossivitsky. Louis was a nephew of Berenson's father, Albert Valvrojenski, the orphaned son of his sister. On arrival in the U.S. both Koussivitsky and Valvrojenski took the name of Berenson. Her sister, Berry Berenson, was an actress/photographer, and the wife of actor Anthony Perkins. Berry died in the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York City.

Among US collectors of the early 1900s, Berenson was regarded as the pre-eminent authority on Renaissance art. Early in his career, Berenson developed his own unique method of connoisseurship by combining the comparative examination techniques of Giovanni Morelli with the aesthetic idea put forth by John Addington Symonds that something of an artist's personality could be detected through his works of art.[11] While his approach remained controversial among European art historians and connoisseurs, he played a pivotal role as an advisor to several important American art collectors, such as Isabella Stewart Gardner, who needed help in navigating the complex and treacherous market of newly fashionable Renaissance art. Berenson's expertise eventually became so well regarded that his verdict of authorship could either increase or decrease a painting's value dramatically. In this respect Berenson's influence was enormous, while his 5% commission made him a wealthy man. (According to Charles Hope, he "had a financial interest in many works...an arrangement that Berenson chose to keep private."[12] ) Starting with his The Venetian Painters of the Renaissance with an Index to their Works (1894), his mix of connoisseurship and systematic approach proved immensely successful. In 1895 his Lorenzo Lotto, an Essay on Constructive Art Criticism won wide critical acclaim, notably by Heinrich Wölfflin. It was quickly followed by The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance (1896), that was lauded by William James for its innovative application of "elementary psychological categories to the interpretation of higher art". In 1897 Berenson added another work to his series of scholarly yet handy guides publishing The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. After that he devoted six years of pioneering work to what is widely regarded as his deepest and most substantial book, The Drawings of the Florentine Painters, which was published in 1903. In 1907 he published his The North Italian Painters of the Renaissance, where he expressed a devastating and still controversial judgement of Mannerist art, which may be related to his love for Classicism and his professed distaste for Modern Art. His early works were later integrated in his most famous book, The Italian Painters of the Renaissance (1930), which was widely translated and reprinted. He also published two volumes of journals, "Rumor and Reflection" and "Sunset and Twilight". He is also the author of Aesthetics and History and Sketch for a Self-portrait.

His beautiful residence in Settignano near Florence, which has been called 'I Tatti' since at least the 17th century became The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, a research center offering a residential fellowship to scholars working on all areas of the Italian Renaissance. He had willed it to Harvard well before his death, to the bitterness of his wife Mary. It houses his art collection and his personal library of books on art history and humanism, which Berenson regarded as his most enduring legacy. A spirited portrait of daily life at the Berenson "court" at I Tatti during the 1920s may be found in Sir Kenneth Clark's 1974 memoir, Another Part of the Wood. 'During WW2, barely tolerated by the Fascist authorities and, later on, by their German masters, Berenson remained at "I Tatti". When the frontline reached it at the end of the summer of 1944 he wrote in his diary, "Our hillside happens to lie between the principal line of German retreat along the Via Bolognese and a side road...We are at the heart of the German rearguard action, and seriously exposed.". Remarkably, under his supervision the villa remained unharmed. Also unharmed was the bulk of his collections, which had been moved to a villa at Careggi. However, Berenson's Florence apartment in the Borgo San Jacopo was destroyed with some of its precious contents during the German retreat from Florence.[13] Another memoir with personal reminiscences and photographs of Berenson's life in Italy before and after the war is Kinta Beevor's "A Tuscan Childhood". Through a secret agreement in 1912, Berenson enjoyed a close relationship with Joseph Duveen, the period's most influential art dealer, who often relied heavily on Berenson's opinion to complete sales of works to prominent collectors who lacked knowledge of the field. Berenson was quiet and deliberating by nature, which sometimes caused friction between him and the boisterous Duveen. Their relationship ended on bad terms in 1937 after a dispute over a painting, the Allendale Nativity (a.k.a. the Adoration of the Shepherds now at the National Gallery in Washington), intended for the collection of Samuel H. Kress. Duveen was selling it as a Giorgione, but Berenson believed it to be an early Titian. The painting is now widely considered to be a Giorgione. Beside assisting Duveen, Berenson also consulted for other important art dealerships, such as London's Colnaghi and, after his breakup with Duveen, New York's Wildenstein. In 1923, Berenson was called to give expert witness in a famous case brought by Andrée Hahn against Duveen. In 1920 Hahn wanted to sell a painting[14] that she believed to be a version of Leonardo's La belle ferronnière and whose authorship is still debated. Duveen publicly rejected Hahn's Leonardo attribution of the painting, which he had never seen. Consequently, Hahn sued him. In 1923 Hahn's painting was brought to Paris to be compared with the Louvre version. Duveen mustered Berenson's and other experts' support for his opinion, dismissing Hahn's painting as a copy. At the trial in New York in 1929, where the expert witnesses did not appear, the jury was not convinced by Berenson's Paris testimony, in part because, while under cross-examination there, he had been unable to recall the medium on which the picture was painted. It was also revealed that Berenson, as well as other experts who had testified in Paris, such as Roger Fry and Sir Charles Holmes, had previously provided paid expertise to Duveen. While Duveen, after a split verdict, ended up settling out of court with Hahn, the whole story damaged Berenson's reputation. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1958.[15] Berenson died at age 94 in Settignano, Italy. Recent scholarship has established that Berenson's secret agreements with Duveen resulted in substantial profits to himself, as much as 25% of the proceeds, making him a wealthy man. This clear conflict of interest has thrown into doubt many of his authentications for Duveen and a number of these have been shown, through careful examination, to have become more optimistic, therefore considerably more valuable, once he was working for Duveen. No systematic comparison has, as yet, been done, but a partial study of 70 works points to this possibility. The issue is still controversial. In addition to his better-known collection of Italian Renaissance paintings and objects, Berenson also demonstrated a keen interest in Asian art, including a distinguished collection of Arab and Persian painting.[16]

My published books: